Canada and the Future of Trade: Theory, Policy and Numbers

Canada’s milestone trade agreements — the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, and more than a dozen other bilateral and plurilateral deals — were all forged from a posture of openness and a belief in the positive benefits of liberalized trade. Recent geopolitical tensions and economic disruptions have raised questions about the future of global trade. Kevin Page, president of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy and Policy contributing writer, looks to the numbers.

Kevin Page

Canada is a wealthy country. Our high quality of life is consistently recognized in global rankings, including by the United Nations Human Development Index, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Better Life Index and the US News & World Report Best Countries in the World rankings. There are many important factors that have underscored our success, including our location and geography, our bountiful natural resources and relatively strong systems of education, health, and governance. This combination of factors has enhanced our ability to trade in the global marketplace and grow our collective wealth.

The late British philosopher and public intellectual Bertrand Russell once said “In all affairs, it’s a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.” As we look back on the significant trade agreement activity over the past three decades, what role can Canada play to strengthen trade and international relations to improve economic, social and environmental outcomes at home and abroad? Can we remain committed to the principles that promote freer trade in a world facing significant geopolitical stress?

Statistics Canada tells us that one in six Canadian jobs is linked to exports. We are an open economy. When the global economy does better, we do better. Economists using macroeconomic models to assess welfare gains estimate that “freer trade” has contributed an additional 15 to 40 percent to real incomes in Canada. The economic pie is much bigger thanks to trade. Canadian consumers also get more selection of goods and services at lower prices.

Does freer trade guarantee better economic and social outcomes for all? No. Does it grow economic opportunity and wealth that could be used to improve general well-being? Yes – the evidence is compelling.

In 1998, The Economist magazine said, with some cheek: “Economists are usually accused of three sins: an inability to agree among themselves; stating the obvious; and giving bad advice. In the field of international trade, they would be right to plead not guilty to all three. If there is one proposition with which virtually all economists agree, it is that free trade is almost always better than protection.”

The economic theory supporting freer trade goes as far back as Adam Smith (Wealth of Nations, 1776) and David Ricardo (On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817). Not exactly household names, but thinkers whose views on economics have influenced the fate of households across generations.

The basic theoretical constructs evolve around concepts such as comparative advantage – which promotes the use of specialization and the development of economies of scale; and trade creation, whereby the reduction of barriers enhances competition and innovation.

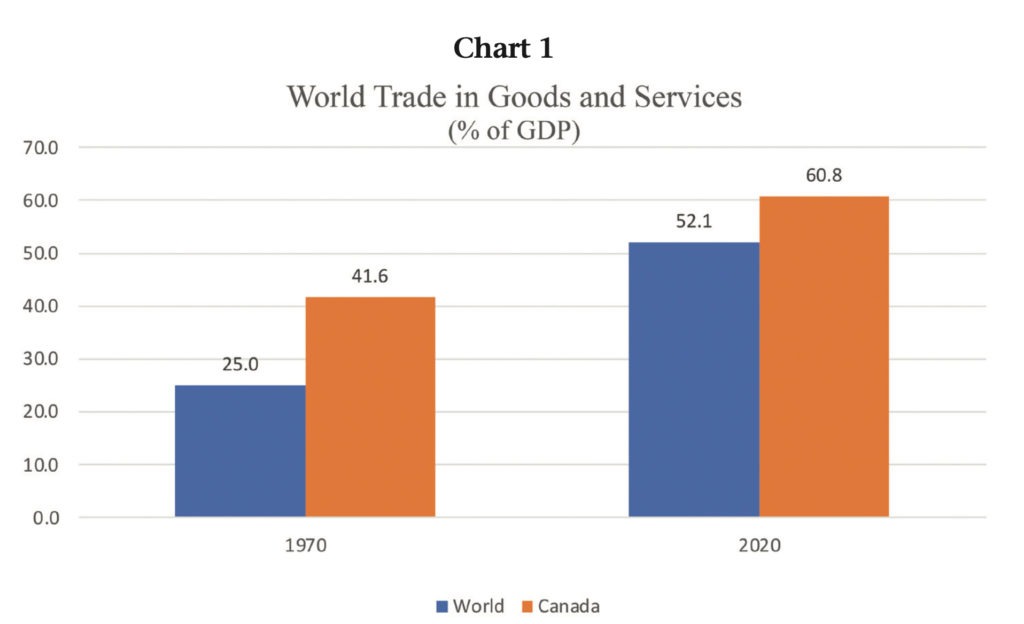

Trade as an engine of growth is seen in the rise in global GDP and trade since the development of the World Trade Organization (WTO). With global rules and regulations, real net exports have grown on average by 7 percent per year. Over the last 50 years, the share of trade in global GDP has risen from 25 percent to 52 percent (Chart 1). For Canada, that share has gone from 42 percent to 61 percent.

Vaclav Smil, the Professor Emeritus at the University of Manitoba, makes the case in his book How the World Really Works (2022) that globalization and trade are not forces of nature bound to continue expanding. Successive waves of globalization and trade expansion depend on a combination of factors – technical prime movers (e.g., engines and turbines) that facilitate the movement of goods and services; new ways of communication that can bring us together and drive innovation; and political and social conditions. With respect to the latter, international peace and order is good. Multilateral, bilateral and regional trade agreements are good. War is bad.

Like many economies after the Second World War, Canada’s exposure to international trade agreements started with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. The GATT process included eight rounds of multilateral trade negotiations before its role was largely superseded by the WTO in 1995. With more economies joining the WTO, we have seen a proliferation of bilateral and regional agreements (more than 350).

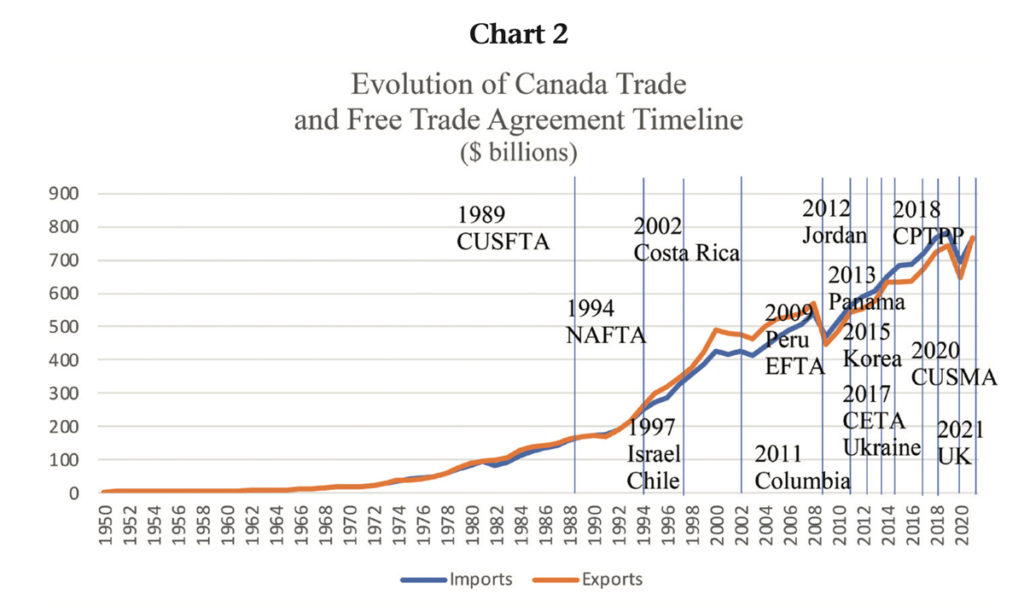

Chart 2 illustrates that Canada’s experience with bilateral and regional agreements started with the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in 1989. Canada now has 15 free trade agreements (FTAs) in place. The trend has accelerated. These agreements have been negotiated and signed by both Conservative and Liberal governments. Freer trade has become bipartisan.

FTAs cover 51 countries representing more than 60 percent of global GDP and 1.5 billion consumers. The arguments for these bilateral and regional agreements are tied to geography (e.g., North America) and the prospects of promoting shared systems and values (Europe, Asia, South America). The concerns relate to the enormous gaps in the bilateral and regional FTA strategy (i.e., no China, no India, etc.), a reflection, increasingly, of the tension between the shared systems and values of democracies and those of autocracies as geopolitical ructions have registered across the diplomatic, commercial and legal realms of world trade.

With three decades of experience and data, Global Affairs Canada has undertaken a range of analyses on the impact of FTAs (State of Trade, 2022). The headline results are both intuitive and positive. They include:

- Bilateral trade more than doubles with FTA partners in the ten years after coming-into-force agreements, compared with an average 48 percent growth with non-FTA partners;

- Exports of products that benefited from tariff reductions grew faster than products with no FTA treatment;

- Trade growth among products with tariff reductions of more than 10 percent grew faster than products with modest reductions in tariffs; and

- Economic research supports significant productivity gains in our manufacturing sector in the years following the Canada-US FTA.

The anti FTA arguments among economists largely relate to special conditions involving development — protecting young industries, culture and the environment; encouraging diversification in developing economies; and guarding against dumping (selling of excess stock at low prices for strategic interests). These are tough issues that need to be addressed in the new, modern FTAs.

Perhaps the most stinging general criticism on the promotion of freer trade has come from Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz. He argues that theories of free trade are largely based on the assumption of efficient markets and ignore the challenges of mobility for labour to move from less efficient firms.

Research on the labour impacts of modern FTAs is ongoing. There is some evidence that workers with less attachment to the work force do struggle with adjustment related to FTAs. Higher skilled workers are more likely to get the greater benefits from freer trade. Bottom line: governments promoting freer trade must do more to strengthen labour market policies and social safety nets to promote adjustment and fairness.

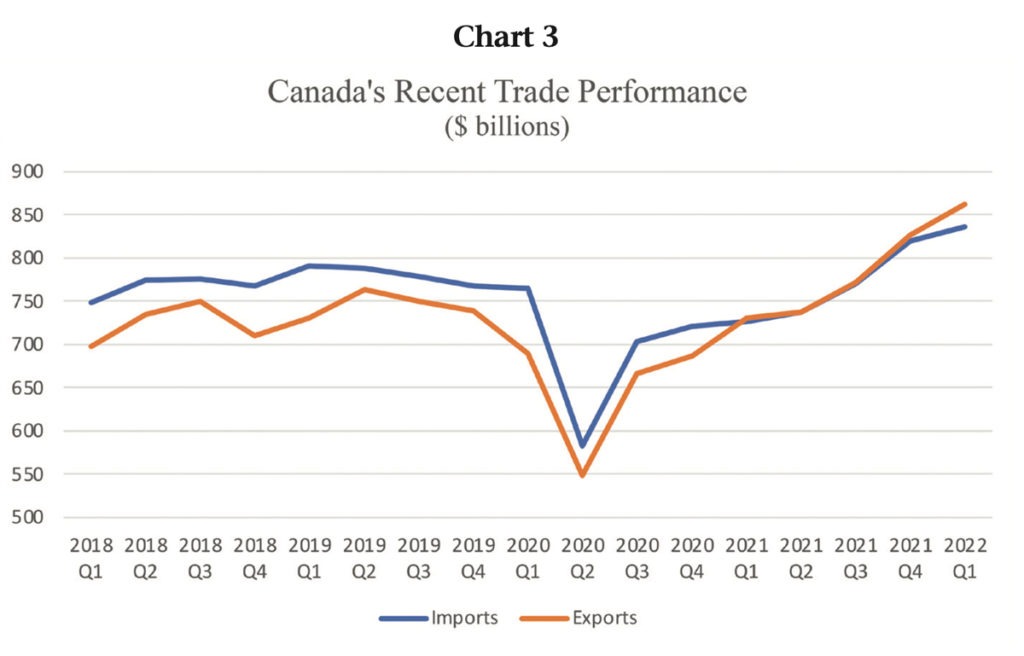

In the wake of the COVID pandemic lockdown and amid the commodity, supply chain and other economic disruptions of the war in Ukraine, there is much uncertainty about the global economic outlook. So far, the trade numbers have not raised red flags. The value of global trade and Canadian trade continue to point upwards in 2021 and 2022. While this is good news, it comes with an asterisk. The growth in value is largely driven by higher prices for natural resources. Numbers on quantities of trade for both goods and services are struggling to get back to pre-COVID levels.

The latest United Nations Conference on Trade and Development report (July 2022) highlights six major issues for trade watchers to follow.

- Downward adjustments to the global economic growth outlook will weaken trade prospects.

- The Russian war in Ukraine will continue to put upward pressure on energy and food prices resulting in higher trade values but likely lower trade volumes.

- Ongoing supply challenges from COVID and rising levels of economic uncertainty will promote a move to shorten supply chains and increase diversification.

- Trends toward intra-regional agreements (e.g., Africa) could come at the expense of inter-regional agreements struggling with high transport costs and geopolitical tensions.

- The impact of higher energy prices and government regulation on carbon should boost demand and trade for green energy alternatives.

- Higher interest rates will increase financial stress on highly indebted countries and weaken investment and trade flows.

Over the past three decades, Canada and much of the world were firmly committed to freer trade. In retrospect, the increase in integration has heightened our vulnerability to global shocks, on the one hand, and promoted greater resilience when they strike through trade diversification, on the other.

In periods of significant geopolitical stress, can we continue to adapt to changing times but remain committed to principles that support freer trade?

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.