Thomas Mackay, Ottawa’s Master Builder

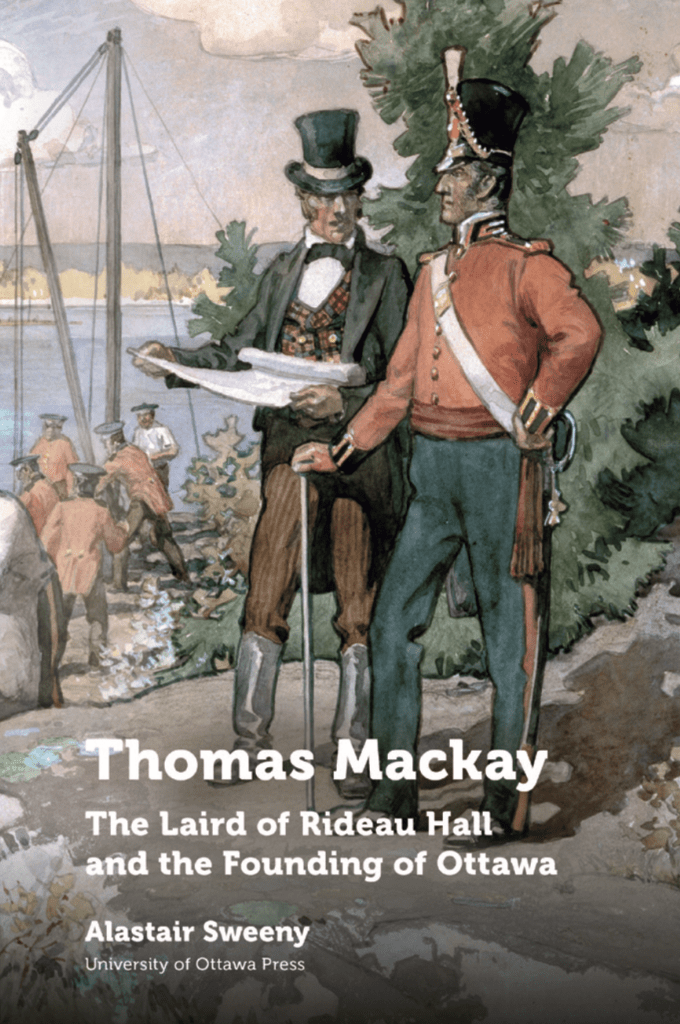

Thomas Mackay: The Laird of Rideau Hall and the Founding of Ottawa.

By Alastair Sweeny

University of Ottawa Press, 2022

Review by Anthony Wilson-Smith

Ottawa has always been easy to mock. The 19th-century British journalist Goldwin Smith called it a “Sub-arctic lumber-village converted by royal mandate into a political cockpit.” The late political columnist Allan Fotheringham memorably referred to it as “the city that fun forgot.” Like many capitals, its name is shorthand for Big Government, including the notion of it as a smug, staid place devoid of adventure.

Having lived there twice for extended periods, I can say that Ottawans generally don’t worry about any of that; they’re too content with the city’s many real charms to care. And, as the writer-historian Alastair Sweeny ably demonstrates, many clichés don’t stand up to proper study of the city’s colourful history. Sweeny, in his deeply-researched new book Thomas Mackay: the Laird of Rideau Hall and the Founding of Ottawa, paints a vivid picture of a remarkably talented, relatively little-known man who helped found the city, of its drama-filled early days and the way in which Mackay’s achievements still underpin Ottawa’s existence.

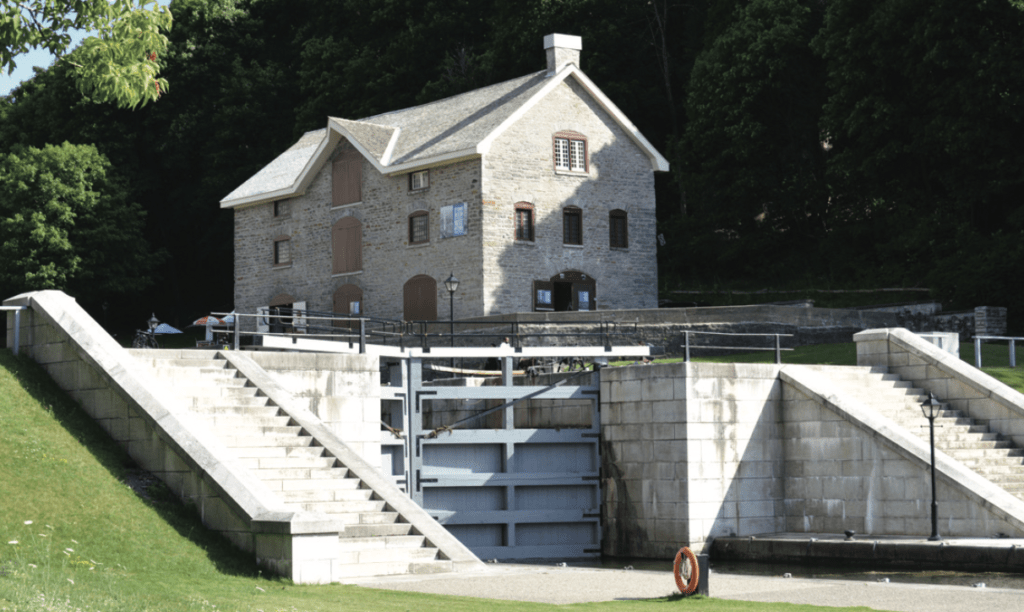

Those achievements were – literally – ground-breaking. He came to Canada as a young man from Perth, Scotland, because of the recession there, and the promise of work here. In Montreal, he teamed with fellow mason John Redpath on projects that remain prominent. Those include building the locks of the first Lachine Canal, arranging the stone for Notre-Dame Basilica, and building the Youville Stables in Old Montreal (where Gibby’s restaurant is now located.)

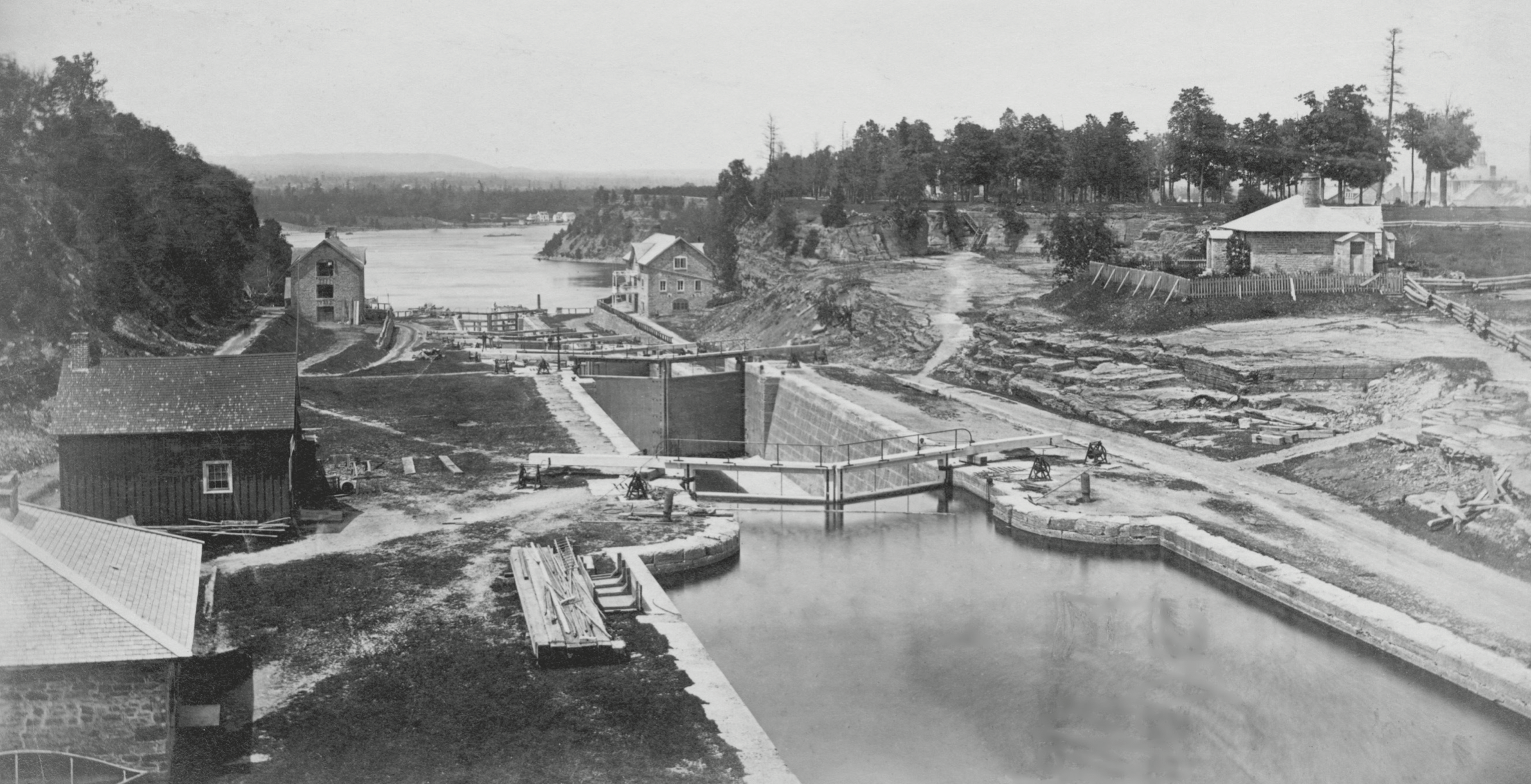

Lured to Ottawa when it was still run by the British military, Mackay oversaw the building of the locks of the Rideau Canal, which UNESCO describes as “a masterpiece of creative human genius.” He played a key role in building Earnscliffe House (where the British High Commissioner resides) and Rideau Hall, the official residence of Canada’s governors general.

As builder and elected politician — as member of the Bytown council and, later, the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada — he helped found the tony community of New Edinburgh and owned the land that became Rockcliffe Park, home ground for the wealthy, along with foreign diplomats and embassies.

Mackay did all this despite frequent tragedy in his life. Of the 16 children of he and his wife, Ann, several died from smallpox, others of tuberculosis; three from drowning, and their oldest son died in India while on service in the British Army. Devout Calvinists, Mackay and Anna relied on faith to overcome their grief.

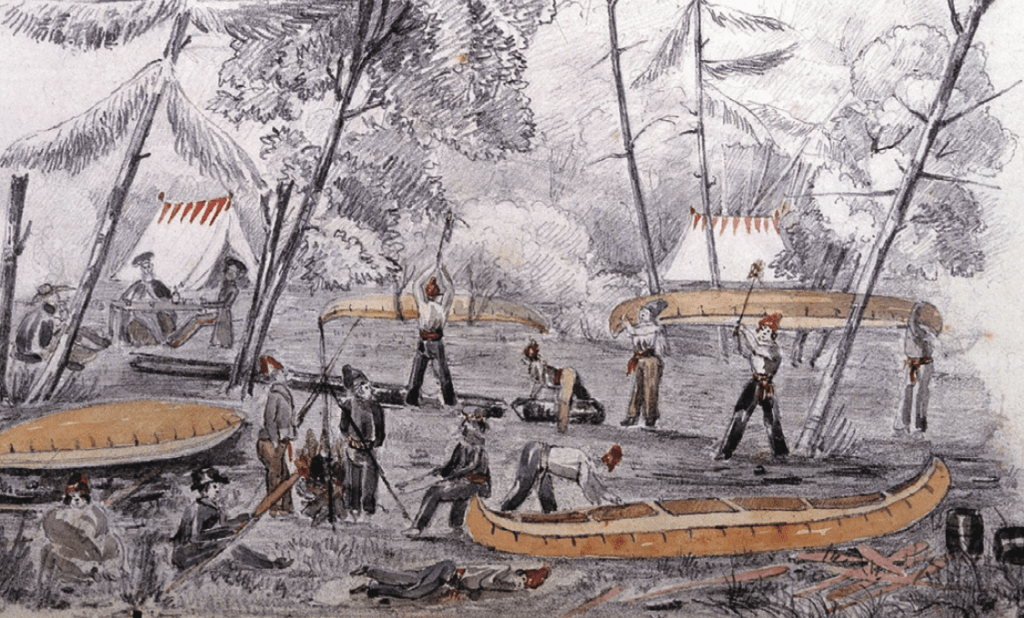

Sweeny, who has worked with my organization, Historica Canada, on past projects, is a superb researcher. In documenting Mackay’s life, Sweeny – who says doing so was “First a hobby and then a passion” over 15 years – turns a challenge into an advantage. Scant first-hand material from Mackay exists, so it is difficult to give him direct voice. Instead, Sweeny pans wider and provides dramatic evidence of the challenges inherent in building a city amid wilderness, in temperatures well below freezing for much of the year.

Unexpected blizzards were common; few workers were dressed for it. At any time, up to 60 percent of canal workers were ill with malaria. Other diseases were also rampant, and medical care was hit-and-miss.

Sweeny has a keen eye for intriguing details. Much of the financing for the canal – central to Ottawa’s growth – came from the seized treasure of European wars. Documentation from the Anishinabeg First Nation describes the ‘strange persons’ they discovered when the military arrived on their land. Capt. John LeBreton, after whom the LeBreton Flats area of the capital is named, was a land speculator so reviled that when he was attacked and beaten, authorities refused to lay charges against the perpetrators.

— John By, McCord Museum, M386.

The fortune Mackay built was largely drained late in his life through his financing of the Bytown & Prescott Railway. The project was essential to Ottawa’s chances to become the nation’s capital – so he persevered despite the losses. Mackay died in 1855; Ann lived for another 24 years. His son-in-law, Thomas Keefer, put in place the final elements of Mackay’s legacy, including the establishment of Rideau Hall as the Governor General’s residence, and the planning of the Rockcliffe Park community. Keefer – whose life calls for expanded study of its own – remained active into his 90s, and died in 1915.

Without Mackay, there might not be an Ottawa. Some of Montreal’s most memorable structures might not have been built – or, at least, built so well. With this book, Sweeny makes us aware of a man who, with bare hands, determination, and technical brilliance, led the building of structures and a city familiar to all Canadians. His real legacy is secure, even if his place in history has not been so — until now.

Contributing writer Anthony Wilson-Smith, President and CEO of Historica Canada, is a former Editor-in-Chief of Maclean’s.