Putin’s Fateful War of Choice

On behalf of the world, the Secretary-General of the UN said February 23 on the eve of Russia’s all-out assault: “President Putin, stop your troops from attacking Ukraine. Give peace a chance. Too many people have already died.” He went ahead, with implications unknown at time of writing. The narrative informing events between Russia and Ukraine, Russia and the West and Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden dates back to post-Cold War loose ends of the 1990s. Longtime senior diplomat and former Ambassador to Moscow Jeremy Kinsman, who was there, explains.

Jeremy Kinsman

Foreground: Russia has invaded Ukraine, all of it, as naked an aggression as the world has seen since 1939.

The US has for weeks been predicting Russia intended to invade. This unilateral aggression of choice has prompted almost universal condemnation, and severe sanctions against Russia.

Putin seems confident Russia can withstand economic sanctions because of its low debt and very ample reserves ($620 billion), the strong price of oil and gas, his presumption China will substitute its economic support (not certain), and proven Russian resilience. But Russia’s certain international isolation as a pariah state will be very uncomfortable. Domestic political support for war and its consequences are low. Vladimir Putin’s justification on grounds of Russian grievances, past and present, will possibly play much less well than the dictator in his bubble believes.

How did it come to this, a flagrant violation of international law, thorough disruption of international behavioural norms, and of European peace that have governed affairs for three quarters of a century? What do we need to understand about Russia? Where to begin?

Background. “Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner” (To understand all is to for-give all). This classic French aphorism, lifted by both Tolstoy in War and Peace and Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead

Revisited, is a romantic notion. Understanding what makes others tick, especially adversaries, is vital. But in diplomacy, forgiveness is irrelevant. Diplomacy seeks livable, workable, outcomes from clashes of interests, values, and even memory, requiring give and take.

Sadly, for this, diplomacy has succumbed to sheer force, for now.

Understanding where the antagonist, Russia, is coming from is buried in traumas of its murderous 20th century history. Putin cherishes distant 10th century ties, when Vladimir the Great adopted Christianity for the Kievan Rus, foretelling the spread of Eastern Orthodoxy into greater Russia. He implies this suggests Ukraine/Russian issues are “family” matters. But Tolstoy also reminded us each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way (and some can break up violently).

Start instead with the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, which enveloped everybody across the Russian Empire in shared traumatic unhappiness from violent Soviet police-state Communism.

PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, can affect whole societies. Soviet trauma was suppressed by the immediate need to resist Hitler’s murderous invasion and by pride in postwar industrial and scientific accomplishments. But Stalinist persecution of Ukrainian kulaks (wealthy farmers), state-created starvation, gulags, and mass purges left cumulative psychological scarring.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s transformative programs of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (reconstruction) in the mid-1980s, to undo the police state and to open up society and the economy, were seen in the US as acceptance of dysfunctional inability to compete in the arms race and the international economy.

The USSR economy could have staggered on several more years. Gorbachev’s principal motive was a moral judgment that transformation of Soviet society needed prior relief of the legacy of state crime. In advocating for openness and truth, he isolated Eastern European puppet regimes, enabling mass dissent that exploded in November, 1989, with the breach of the Berlin Wall. The tumble of Communist regimes eviscerated the Warsaw Pact of meaning. At the Open Skies meeting in Ottawa in January, 1990, West Germany and East Germany, (GDR), agreed with the Second World War’s occupying powers, the USSR, the US, France and the UK (“two plus four”) to negotiate Germany’s reunification. It was the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

NATO ministers next met June 7th, 1990, under Margaret Thatcher’s chairmanship at Turnberry Golf Course in Scotland (now owned by Donald Trump). German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher agreed to propose a “Message from Turnberry” to “seize the historic opportunities resulting from the profound changes …. to help build a new peaceful order in Europe.” German Political Director Dieter Kastrup asked his Canadian counterpart, me, to shape the English. Together, with External Affairs Minister Joe Clark’s encouragement, we crafted NATO’s short message, “to extend to the Soviet Union and to all other European countries the hand of friendship and cooperation.” Headlines the next morning signaled the actual end of the Cold War. The euphoria wouldn’t last.

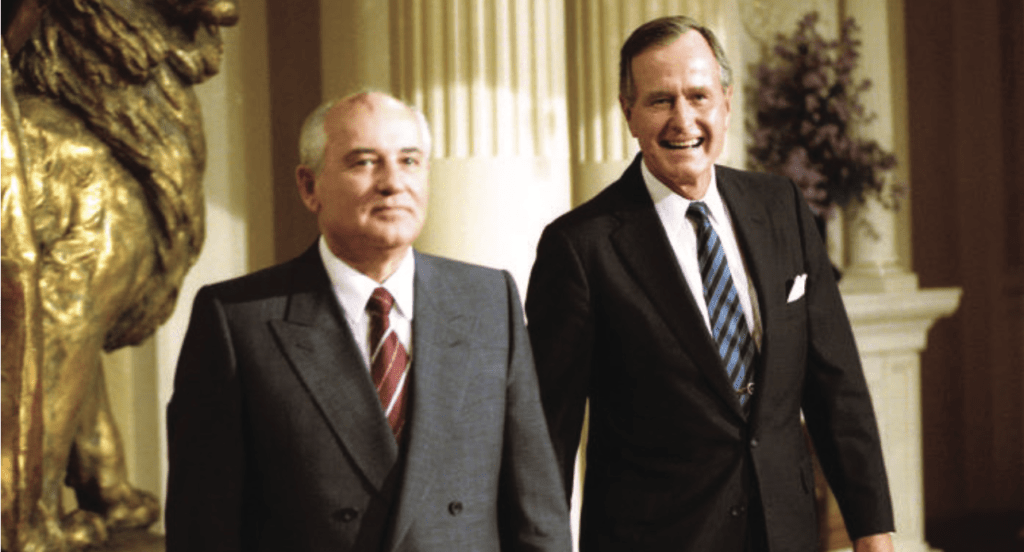

Germany’s reunification needed prior withdrawal of 400,000 Soviet troops. Chancellor Helmut Kohl offered Moscow massive financial compensation. At a Bush-Gorbachev summit in early September 1990 in Helsinki, Secretary of State James Baker (presented as “my lawyer,” by George H.W. Bush) assured Gorbachev that as USSR forces pulled out of East Germany, NATO forces would not move “one inch” to the East. Baker says he meant “into East Germany.” Gorbachev regrets his that his acquiescence implies he had accepted NATO expansion.

Having myself asked both Baker and Gorbachev in their retirements, I concluded the question was lost in translation at the buoyantly cordial Helsinki summit where, as Baker told NATO the next day, Gorbachev endorsed a UN-sponsored international force to reverse Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait a month earlier. Discussion intensified over Europe’s security architecture in light of momentous changes. Some leaders – Germany’s Genscher, Czech leader Václav Havel – questioned the need for both NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

In November 1990, a grandiose Europe-North American Paris summit described as the Cold War peace conference launched Gorbachev’s concept of a European common home, from “Vancouver to Vladivostok.” It created the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). In June, 1991, at the post-Gulf War G7 London Summit, Gorbachev’s guest appearance on the veranda of Lancaster House drew officials lunching in the garden below spontaneously to their feet to applaud the man most of them credited with ending the Cold War.

But the summer’s confidence waned as unprecedented transformation challenges arose. In Warsaw, Budapest and Prague, newly empowered political dissidents with scant experience of running anything, much less governments, found that opposition to prior Communist regimes didn’t extend to unity on what to do next. These Western European societies shut in by the Iron Curtain, yearning to re-join Europe, now grasped that satisfying entry requirements of the European Community would be a long and hard road. Havel reversed his inclination to dissolve both alliances, seeing that NATO’s brand offered precious Western identity credentials.

Russian attention was inward. Gorbachev had undertaken emancipation from state Communism without a lucid “Plan B” to transform the economy. No one knew how, least of all Western advisers whose “shock therapy” had triggered economic and social free-fall. An August coup by bitter Communist throwbacks failed, but Gorbachev’s popularity tanked. Rival reformist president of the Russian Republic Boris Yeltsin failed to push him out, so Yeltsin broke up the USSR.

That decision was made December 8th, 1991, at a Belarussian hunting lodge by Yeltsin and Leonid Kravchuk, party boss of Ukraine. On December 20, at the inaugural meeting of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council – the 16 NATO and nine members of the Warsaw Pact – at which I was present in Brussels, the Soviet ambassador, called repeatedly to the phone from Moscow, relayed his instruction to remove the USSR’s nameplate from the table. We adjourned, believing that NATO’s intrinsic vocation as an alliance organized in hostile opposition to Moscow was over. (It would return.)

For 20 years, NATO explored a wider role (summarized in the post-Cold War catchphrase “out of area or out of business”), undertaking airstrikes in 1999 to end Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing siege of Kosovo. After the attacks of 9/11, Canada moved that NATO for the first time activate Article 5 of its Charter to intervene collectively in response to an attack on an alliance member, launching its long and painful engagement in Afghanistan. In 2011, NATO bombed Moammar Ghaddaffi’s army in Libya as it advanced on Benghazi.

Meanwhile, the USSR’s 290 million citizens broke into 15 separate countries, surprisingly peacefully. Twenty million ethnic Russians opted to stay in non-Russian new republics. Concern for Russian minorities in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, the Baltics, Moldova, and Georgia would preoccupy Moscow for years. To fill the national identity space vacated by Communism, leaders of new republics often drew from established hostility to the USSR, which they easily conflated with the Russian Republic. Russians, who had decisively pushed breaking up the USSR and who had suffered more from the Communist oppression than anyone, resented it.

But they remained engulfed by institutional collapse at home. The Russian Navy’s commander told me when I was serving as Canadian Ambassador to Moscow that he was an out-placement manager. We saw rotting hulks of nuclear-powered ships in Vladivostok. Yeltsin begged for material western assistance. US President Bill Clinton understood the potential costs of letting “ol’ Boris” down but couldn’t move Congress to do much to support Russia. By 1998, amid chaos and corruption, Russian democratic reformers fell decisively out of favour. Meanwhile, in 1999 NATO admitted new members, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland.

The post-Yeltsin battle began. His family turned to Vladimir Putin, reputedly a reliable go-to apparatchik who quietly got things done. He replaced Yeltsin on January 1, 2000. His first official foreign visitor was NATO’s Secretary general, George Robertson. Putin successfully redressed economic disarray and stabilized politics to public acclaim, telling Russians that what they needed was not another revolution, but a “Great Russia.”

But his growing subtraction from recently-gained democratic space increased opposition from professional and middle classes, chafing at their imposed “political infancy.” Putin played the popular nationalist card, exploiting what former UK Foreign Minister David Miliband describes as a legacy of Russian humiliation at being treated as the Cold War’s “losers,” to earn applause for standing up to the West. Western dismissal ofRussian positions that NATO’s expansion up to Russia’s borders violates 1990s understandings “outlandish” fuelled the resentment.

Still, most Russians were sufficiently objective to understand that Czechoslovaks, Hungarians, and Poles deserved to re-join interrupted European legacies. Most conceded, too, that the shameful 1940 annexation of the Baltic states into the USSR via a deal with Nazi Germany deserved remedy. The entry of Romania, Bulgaria Slovenia, Slovakia, etc., was sullenly digested.

But it was always clear that NATO’s inclusion of Ukraine or Georgia would cross a red line. Putin manufactured this crisis to protect that line with an unobtainable formal agreement NATO will not expand, though he knows that in reality Ukraine is not joining NATO. He wishes to reclaim for Russia great power influence, and greater Russia/NATO security parity. He believes the “Minsk accords” that meant to stabilize conflict with the rebels of Donetsk and Lugansk and award more autonomy to the Russian-speaking Donbas are hopelessly stalled. He chose aggression against Ukraine for daring to exist.

Putin wanted Ukraine to fail. A successful democratic Ukraine could be mortally contagious to his corrupt autocracy. He is a cynical and highly competitive man who sees democracy idealists as hypocritical, phony US stooges. He prefers believing that a Ukraine subordinate to Putin retain operational features just like Russia’s, where corrupt oligarchs call the shots.

His choice of invading Ukraine, inviting death and destruction, and real costs to his own country, raise issues of the Russian leader’s grasp of reality and certainly of morality.

Does he represent Russian opinion? The surprise 2014 annexation of Russian-speaking Crimea was popular in Russia but almost destroyed relations with the West. By contrast, military incursion and occupation in Ukraine would find little public support (only 17 percent according to a Levada poll wish the two countries to re-unite). It would isolate Russia for years, whatever Putin’s closer but still wary autocratic fraternity with Xi Jinping.

NATO had been ready to address Russian security concerns — on intermediate nuclear weapons, military infrastructure placement, and the bigger picture, before Russia invaded its neighbour. Now, there will be no Summits for Putin with world leaders, probably ever again.

Relations will now enter a nuclear winter of mutual opposition between Putin and the US, the West and even democracy.

We are dealing with the aftermath of momentous events three decades ago. We lazily believed then we were living the “end of history”, heralding universal coalescence around a Western democratic and market-based model. We couldn’t know it would almost crash in the financial collapse of 2008 or that an increasingly autocratic Putin would radicalize his hostile behaviour.

His distortion of truth and lethal threat to lives for the sake of a demonic dream of repossessing a dispossessed past have, as Masha Gessen writes in the New Yorker, made it impossible for decent people in Moscow and Kiev “to live and to breathe.” It must be ghastly for them.

Life may now become ghastly for many more Russians who shrugged their shoulders at Putin’s absurd excesses while enjoying new wealth and travel, now about to be curtailed. He is their disgrace, their madman – no other way to put it.

Nonetheless, we need to understand the past and present to meet author F. Scott Fitzgerald’s functional test of a first-rate intelligence — when things seem hopeless, to determine to make them otherwise.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman, served as Canadian Ambassador to Moscow from 1992-96, as well as Ambassador to Rome, High Commissioner to London and Ambassador to the EU. He is currently a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.