War and Peace in Our Time

Douglas Porter

February 25, 2021

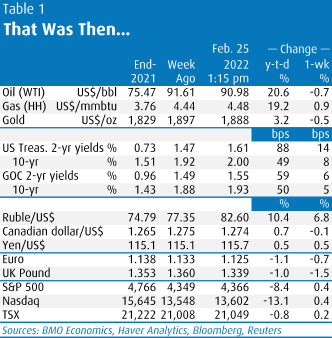

As tensions simmered for months along the Ukrainian border, many pundits noted that markets tended to move past geopolitical events in relatively short order, even major events. Little could they have imagined that traders would seemingly shrug off this week’s Russian invasion in a matter of hours on Thursday. As the attached table suggests, the majority of net market moves on the week were generally mild, with the notable exception of the record low for the ruble. Of course, there were some wild swings in the middle, with oil touching $100 for the first time since 2014, and the Nasdaq exploring bear territory Thursday morning. The absence of a huge weekly move can be attributed to clear indications that: a) the U.S. and NATO will not intervene directly in Ukraine, and b) sanctions will be targeted, and will not include much more serious steps such as energy or SWIFT, for the time being.

But while the week’s net market moves may have been nondescript, the year-to-date shifts are much more telling. Oil has stepped up by more than 20% (at least partly due to Russia’s actions), short-term yields have fired higher amid persistent inflation pressure, and stocks have struggled accordingly—the S&P 500 hit correction territory Tuesday for the first time since the opening weeks of the pandemic. Moreover, even with this week’s quick market reversal, no one can know what’s next in Eastern Europe. And the co-operation between Russia and China on this file is rather disconcerting. At the very least, the geopolitical risk premium has been cranked higher.

In terms of the more immediate economic and financial impact on the rest of the world, the reality is that the global economy was already staring down the barrel of much higher oil prices. And as this week’s Focus Feature notes, ultimately, energy prices are the major risk factor associated with the conflict in Ukraine (assuming it doesn’t spread further). Given that oil prices have not shifted dramatically on net in the wake of Thursday’s invasion, we won’t yet be making any big adjustments to our global growth (outside of Europe) or inflation outlooks. Having said that, it’s clear that this week’s events put downside risk on growth, and yet further upside risk on inflation, especially with the lingering threat of a true oil shock now much more realistic.

Central bankers now have the difficult task of making real-time decisions in this extremely fluid backdrop. First up next week is our very own Bank of Canada with Wednesday’s scheduled rate announcement. (The Reserve Bank of New Zealand hiked rates 25 bps this week to 1.0%, the very day before the invasion.) Prior to this week’s events, the only debates about the BoC decision were whether they may consider hiking by 50 bps, and whether they would immediately begin actively reducing the balance sheet (QT). Given the Bank’s stated goal of being a source of predictability and stability, the standard issue 25 bp rate hike is now almost a foregone conclusion. Its intentions on the balance sheet are much less predictable, especially since this is the Bank’s first experience with QE/QT. In the past year or so, it has tended to land on the hawkish side of expectations on the balance sheet moves. Indeed, Deputy Governor Lane recently suggested that the BoC could end reinvestment and be on the path to QT at next week’s meeting.

Unlike the Fed, the Bank will need to make its rate decision without the benefit of either the February jobs or CPI reports. But given the ongoing run-up in gasoline prices, and indications of additional strength in many other areas (notably food), we fully expect inflation to take yet another big step up in the next release (possibly to 5.5%). Note that France offered the world’s first sneak peek at February consumer prices, and it wasn’t pretty—up 0.8% m/m. An additional pressure point on the Canadian inflation outlook is that the loonie has actually softened this year even amid surging energy prices, offering no safety valve for consumers and driving pump prices to record highs.

Meantime, on the growth side, this week’s thin gruel of Canadian releases were generally positive, and suggested that the economy held up surprisingly well in the face of January’s restrictions. Both manufacturing sales (+1.3%) and wholesale trade (+3.9%) rose solidly—albeit price-aided—in a month when employment fell 200,000. We had been anticipating a big step back in January GDP, but all sales metrics (also including retail and homes) rose, suggesting only a mild dip in overall activity. And, the steady and sustained drop in COVID cases has allowed many provinces to loosen restrictions, pointing to a rebound in hard-hit sectors this month. Looking further out, the annual survey of capital spending intentions from StatCan was solid at an 8.6% gain for 2022. Still, we’re not rushing to boost our growth forecast given the new risks to the outlook—consumer confidence fell heavily this month to its lowest level in a year, according to the Conference Board.

As for the Fed, we will simply restate comments from last week: The reality is that inflation is now such a heavy-duty risk that the Fed really has little choice but to proceed with hiking, even in the face of conflict. Comments by various officials in the immediate wake of the invasion suggest that the Fed is not about to lose its nerve, with some policymakers still openly discussing a possible 50-bp first step. We believe that the added layer of geopolitical uncertainty will keep the first hike to 25 bps, and still anticipate that this will be the norm for the cycle. However, it is quite instructive that some officials—including Fed Governors—continue to consider more aggressive options. The market’s initial response to the invasion was to trim near-term rate hike expectations. But, just as other markets quickly looked beyond events in Ukraine, so, too, may the FOMC.

Doug Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.