Preparing the Fiscal Planet for a Net Zero Economy

The economic challenges of meeting the climate change commitments of the Paris Agreement and COP26 will require the greatest adjustment to our existing fiscal regimes in decades. That required shift in both spending and global accountability has already prompted action at the international level. Kevin Page and Alexandra Ducharme of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy look at how Canada should respond.

Kevin Page with Alexandra Ducharme

Do we have fiscal planning framework in Canada in place to credibly support the economic transformation consistent with the government’s 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) targets?

No.

Canada, like other advanced countries, will need to re-think how it plans, allocates and reports on the use of taxpayer resources in order to effectively de-carbonize our energy systems and economy.

The process of changing the way budgets look and operate is underway with the help of international leadership from the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The budgetary work to address climate change is being complemented by efforts from international accounting standard boards on sustainability, from central banks on modeling economic impacts, from financial oversight organizations on risk exposure, and from private sector initiatives to promote corporate social responsibility.

In military parlance, this is the equivalent of a full-frontal attack. Can we implement? Can we transform the way political and business leaders make decisions and the way we live our lives given the scale and timelines of global warming as projected by scientists at the United Nations (UN) International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)?

The global strategy is simple and potentially powerful. As articulated by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, we need to create a “virtuous circle of innovation and investment”. Step one: countries turn Paris Climate Change Agreement greenhouse gas emissions targets into legislative objectives and climate policies. These commitments and a vision for a new growth agenda increase certainty for investment. Step two: private finance helps businesses realign its business models for a net zero economy. Step three: public and private sectors work together and adjust plans as needed to smooth adjustment and minimize costs.

The scale and timelines of change associated with the new climate targets in Canada are ambitious:

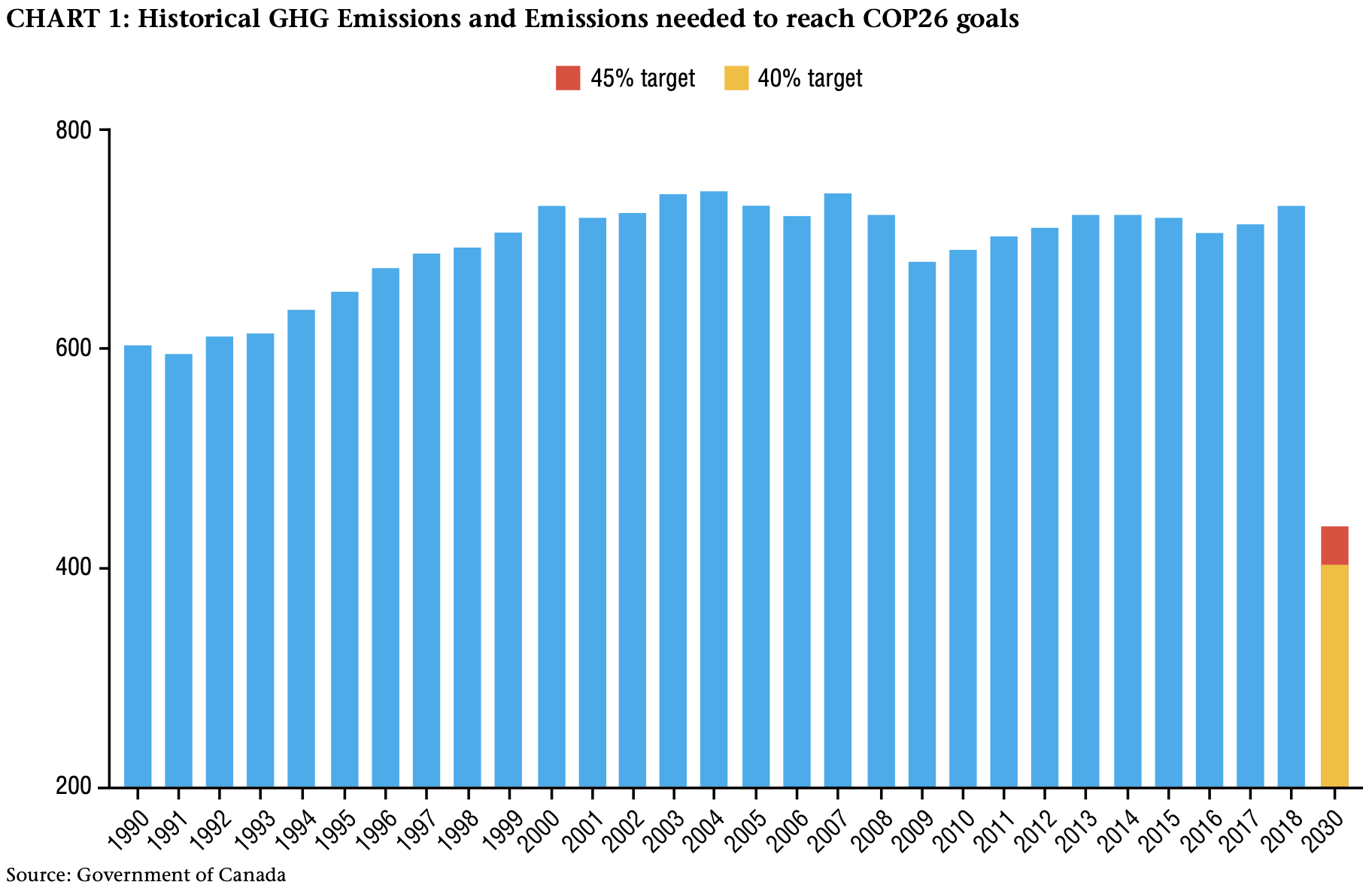

- A reduction in GHG emissions by 40 to 45 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels. GHG emissions remained relatively flat from 2000 to 2020. The pain of adjustment lies in front of us (Chart 1);

- GHG emissions are heavily embedded in current infrastructure of most economic sectors – transportation, oil and gas, electricity, heavy industry, buildings, agriculture, and waste. We do not have a pan-Canadian infrastructure needs assessment;

- A complete re-balancing of our energy sector from non-renewable to renewable supply is required. Energy’s nominal GDP contribution is about $200 billion a year. It employs about 300,000 people directly and 550,000 thousand people indirectly. Canada’s primary energy production represents about four percent of global supply (more than 35,000 petajoules). Renewable energy sources (hydro, bioenergy, wind, solar, geothermal, oceans) account for just under 20 percent of energy supply. We need to plan for an 80-20 reversal;

Canada does not have a good track record when it comes to taking credible and sufficient measures to address climate change.

In recent years, Canada has introduced wide ranging policies to address climate change. Legislation was passed in 2021, the Canadian Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act, that enshrines a net zero GHG emissions target into law. Mandatory carbon pricing has been in effect across the country since 2019. The carbon price is planned to rise significantly ($15 per tonne per year) from $65 in 2023 to $170 in 2030.

According to its 2020 plan, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy, “the Government of Canada has invested over $100 billion toward climate action and clean growth since 2015, with roughly $60 billion from 2015 to 2019 and $54 billion towards Canada’s green recovery since October 2020.” More commitments were made in the 2021 election campaign. These resources are spread across all key sectors. There are monies to encourage innovation in clean technologies (e.g., Net Zero Accelerator Fund). There are numerous regulatory measures (e.g. Federal Greenhouse Gas Offset System, Clean Fuel Standards).

Notwithstanding significant efforts, nobody really thinks we have done enough to put our economy on track to decarbonize and achieve the 2030 and 2050 targets. Even with better price signals and regulations, a $100 billion dollar commitment over a decade to address mitigation and adaption is not going to be enough in a high-carbon per capita economy with a GDP approaching $2.5 trillion a year and an energy sector (80 percent dependent on non-renewables) that generates $200 billion per year.

The global consortium of independent think tanks that produces the Climate Change Tracker rates Canadian plans and efforts as “highly insufficient”. While the domestic targets are rated as average, we score low on domestic policies and actions and international climate finance support.

After spending some $300 billion on direct fiscal supports and a similar additional amount allocated in liquidity measures to address a global health crisis in Canada over a few years, the scale of the effort required to address climate change remains largely un-costed. Analysis by the Canadian Institute for Climate Change Choices (Tip of the Iceberg, 2020) indicates the average cost of a weather-related disaster has gone up more than 1000-fold since the 1970s. Annual economic costs have gone from millions to billions of dollars. The trend line is well- established. The direction is up and steep.

It is in this context that the OECD has started working with member countries to better incorporate climate policy into the budget process and reporting.

According to Robert Marleau and Camille Montpetit, two Canadian experts on parliamentary procedure and practice, budgets are first and foremost “a comprehensive assessment of the financial standing of the government and an overview of the nation’s economic condition.” In a world facing impending dangers from climate change and a global economy struggling to adapt, a nation’s economic condition is tied to the environment. Financial standing includes both fiscal and environmental sustainability and resilience.

The OECD green budgeting framework has four building blocks.

One, a strategic framework:

The Global Commission on Climate and Economy has made the case that we need a new growth agenda for a climate economy that focuses on the interaction between technology innovation, sustainable infrastructure and resource productivity. Canada does not have a growth strategy. Canadian economists and former senior Finance Canada civil servants such as David Dodge and Don Drummond have called for an investment orientated growth strategy – missing from all party platforms in the 2021 federal election campaign.

Two, evidence generation and policy coherence:

Current public finance management frameworks need to systematically incorporate information on environmental and/or climate impacts. This includes green budget tagging where all new measures are assessed from an environmental perspective. France and Ireland have started this practice. Spending reviews should be conducted from a climate goal and efficiency/effectiveness perspective. US President Joe Biden has recently announced a net zero federal government target for 2050 with interim goals for specific sectors (including buildings and vehicles).

The Liberal 2021 party platform highlighted the need for federal spending reviews. Budget 2021 highlighted a commitment to a national infrastructure needs assessment. The government should move forward with these initiatives in 2022. Green budgeting should complement the work of the government on gender budgeting.

Three, accountability and transparency:

Effective scrutiny both before authorities are provided by Parliament and after the money is spent through evaluation and audit are necessary for good fiscal management of taxpayer dollars. The OECD recommends the use of a Green Budgeting statement to inform Parliamentarians, stakeholders and citizens how fiscal policy is being used to support climate objectives.

The Liberal government has proposed the establishment of a net zero advisory committee to provide advice on pathways to achieve net zero. Consideration should be given to establishing an independent body reporting to Parliament on the efficacy of policies and progress towards emissions targets.

Four, budgetary governance:

A fiscal planning framework for green budgeting needs to include direct links between strategy and budget plans, department spending, performance reporting and citizen engagement.

Climate policy must inform fiscal planning. Economic and fiscal planning outlooks need to be extended to deal with the longer-term horizons of climate impacts. Climate change impacts need to be embedded in baseline and scenario projections. Independent fiscal institutions in the US (the Congressional Budget Office) and EU are making these adjustments. Canada should follow suit.

Green budget statements should make it easy for provinces and territories, cities, First Nations, and the private sector to know how budgets are evolving and their impacts on climate objectives from their perspectives.

Annual meetings of the Council of the Federation (premiers, territorial leaders and others) should include a standing agenda item on climate policy, mitigation and adaption progress.

The Chinese proverb says that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Canada has taken several steps to strengthen its climate policy. Putting those commitments into action through its fiscal planning framework would be a leap forward.

Contributing writer Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa. He was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Alexandra Ducharme is a fourth-year economics undergraduate student at the University of Ottawa.