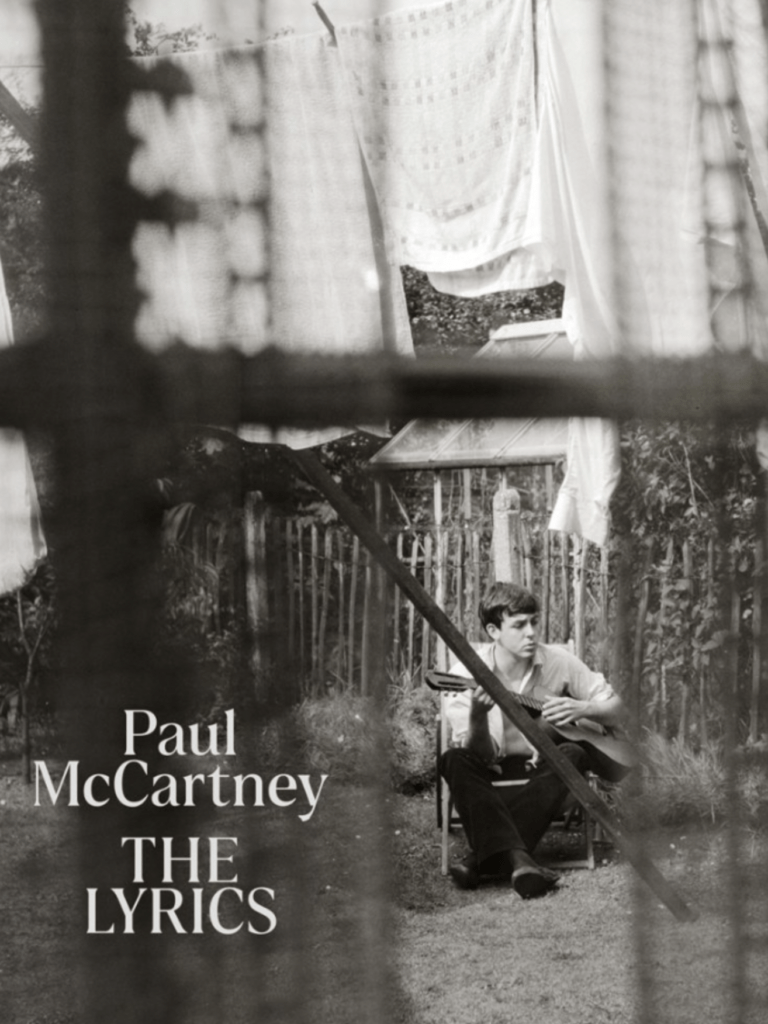

McCartney’s ‘The Lyrics’: It’s Still the Beatles’ World, We Just Live in It

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present

By Paul McCartney

Liveright Publishing/November 2021

Reviewed by Charlie Angus

November 30, 2021

A book on the lyrics of Paul McCartney? I gotta say, I like Sir Paul, but when I first heard of his new project, I was planning to take a pass. Did I really want to read a poetic analysis of Ebony and Ivory? But from the first page, I was hooked.

Paul sets the stage as a young teen in blasted-out, post-war Liverpool growing up in a loving, working-class family. He learned how to harmonize singing dance hall songs around the piano and how to rhyme playing word games with his dad. Ah, so that’s where he came up with killer lines like “Maxwell Edison majoring in medicine”? At 14, Paul got a guitar, learned Eddie Cochran, and the rest is history.

The Lyrics isn’t the memoir of an old geezer reliving glory days. In telling the backstory to so many indelible songs, McCartney remains the king of phrasing, the crystal-clear image and the hook that never lets you go.

I’ve always been torn about the Beatles. Blame it on the chip on the shoulder of a generation growing up in the shadow of the Baby Boom. When I was a teenager, I didn’t rebel against my parents, I rebelled against the Beatles. I was thrilled by the Clash call to arms when they declared, “Phony Beatlemania has bitten the dust.” Dissing the Beatles was how punk kids tried to define our place in the world, and how punk musicians insurrected.

But in my heart, I really couldn’t hate them. When I was a toddler, my teddy bear was named Ringo. When a Beatles song came on, my widowed Scottish grandmother would gather us around the radio so we could hold hands and sing along. She taught us all the Beatles hits.

And in my teens, the murder of John Lennon was a tragic rite of passage into a darker adult world. I mourned the loss even as we railed against the maudlin desire to turn the troubled and turbulent Lennon into a plastic saint. That moment has always stayed with me which is why, decades later, I wrote the song The Day John Lennon Died with my band, Grievous Angels.

Charlie Angus, centre, and former MP Andrew Cash, right, performing with the Juno-nominated Grievous Angels

Charlie Angus, centre, and former MP Andrew Cash, right, performing with the Juno-nominated Grievous Angels

With Lyrics, Paul provides a backstage pass to him and Lennon composing the new western canon of song — a process also immortalized in Peter Jackson’s new epic documentary The Beatles: Get Back, but without the same personal focus, context and perspective from McCartney. We learn that John was imitating Dylan when he sang Hide Your Love Away and that the Beach Boys Pet Sounds hit the Beatles as “serious competition.” They responded with the hilariously subversive Back in the USSR.

At one point in the book, McCartney likens the pressure on him to write a hit song to the pressures faced by Dickens or Shakespeare as they wrote for the fickle London audience. Dickens and Shakespeare? Seriously? But then Paul proceeds to describe getting up in the middle of the night to write Come and Get It as a first single for the Welsh band Badfinger. The next morning, he went into Abbey Road and laid down all the instruments for the demo in 20 minutes (that demo gave Badfinger a massive, worldwide hit). With the demo complete, McCartney spent the rest of the day writing tracks for the monumental work Abbey Road. Not bad for day’s work. I bet Shakespeare and Dickens couldn’t beat that.

What’s fascinating about the Beatles is that their work still sounds fresh and ageless. Elvis died in 1977, but over the decades his sound and image have receded into sepia. The aging Stones are still chugging along, their bad-boy catalogue navigating a #MeToo world. But when it comes to John, Paul, George and Ringo young people are continually rediscovering them. Recently I watched the film Hard Days Night with a young Gen Zed. She said she loved the movie because it showed the Beatles “standing up to the boomers.”

Boomers? Wait a minute. The Beatles were the soundtrack for the boomer generation. But my attempt to explain this to Gen Zed went nowhere. To Gen Zed, the boomers are stuffy older people, resisting change. Not only do the Beatles get exempted from the fault lines of a new generational war but they are welcomed as allies by kids who see them the way we did – as the perpetually young and brilliantly charismatic lads from Liverpool.

The downside of the book is, of course, the reminiscences about the decades of solo songs after the Beatles. McCartney has written some great songs in the half-century since the Beatles’ break-up, but the stories with Wings just don’t convey nearly the magic of stories about Eleanor Rigby or Sgt. Pepper. But then, how could they? Nonetheless, the photos and notes make up for any shortfall.

The Lyrics lands as the world is going gaga over all eight hours of practicing and bickering in Get Back. We are enthralled by the forensic tedium of the film because we want answers: what was the secret magic that made these four musicians so Goddarned brilliant? It’s the same thing with Lyrics. Sometimes it still feels — to paraphrase Dean Martin on a different musical deity — like it’s the Beatles’ world and we just live in it.

Charlie Angus is the co-founder of the punk band L’Étranger and longtime front man for the Grievous Angels. He is the New Democratic Party member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay.