A Post-Pandemic Primer for Our Bilateral Business

America’s domestic coherence problems and global preoccupations have not dissipated in the wake of Donald Trump’s defeat. Through decades of navigating bilateral relations through the prism of trade, energy and security priorities, Thomas d’Aquino has seen a range of presidential postures toward Canada, and, he writes, Joe Biden’s bodes well. With a couple of cautions.

Thomas d’Aquino

As Canada prepares for a post-pandemic world, our country needs to re-set our relationship with the United States. It’s also high time that we apply some badly needed realpolitik to the relationship.

We may indeed be “closest friends and allies”—terms that many of us have happily uttered many times over in our lifetimes—but we also must accept that national interest in the end must be the key driver. The national interest in the American context is rooted in the celebrated saying of the late House Speaker Tip O’Neill that “all politics is local”. It is also driven by fiercely advocated partisan interests. “Closest friends and allies” may sound good and give some of us comfort but in day-to- day terms, it’s not the real world. Our differences on trade, energy, climate change and foreign policy issues, felt strongly on both sides of the border, prove my point.

Think back to the time when the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement was negotiated. Thanks in part to the remarkable relationship enjoyed by Prime Minister Mulroney and President Reagan, it was a time when we thought much more about what we might accomplish together than what divided us.

This was not just the case at the political level. In my position then as head of the BCNI, today’s Business Council of Canada, I was privileged to play a private sector leadership role in helping advocate for close Canadian-American economic cooperation, and we could count on powerful business allies in the American business community. In the early 1990s, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) incorporating Mexico moved the continental relationship to a trilateral dimension. We were full of big ideas then, arguing that North America would become the most competitive regional economic powerhouse in the world. After the shock of 9/11, the three countries went even further by signing the ambitious Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP). At the time, we even dared talk about a North American “community”.

But we are far from that ideal today. What happened?

In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008, the Obama administration cancelled the SPP. The crisis shook Canadian confidence in American finance. All the while, protectionist forces in the US, which had never receded, began to reassert themselves. And then came Donald Trump with his America First polices and his ferocious denunciations of the NAFTA as “the worst trade agreement in history”. Heading the most disruptive presidency in modern American history, Trump knocked the traditional Canada-US relationship off its axis. His threats to walk away from NAFTA, coupled with his bullying and insults, considerably soured Canadian public opinion toward our southern neighbour. His capricious trade actions on aluminum and steel, his repudiation of the Paris Agreement on climate change and his unsettling statements about the relevancy of NATO as “obsolete” only made matters worse.

Joe Biden’s arrival in office is greatly encouraging. His deep political experience and sound character are strong pluses. His re-affirmation of traditional American foreign policy and defence positions is reassuring. The fact that he chose to meet with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau before any other foreign leader is significant. His talk about the pre-eminent friendship binding our two countries is certainly welcomed by Canadians. So was his decision to re-engage America in the Paris Agreement.

But, the Democratic party has a powerful economic nationalist and protectionist element within it. Evidence of its sway can be seen in President Biden’s Buy American executive order. Cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline on his first day in office offers further evidence. Since the president’s move against Keystone, various actions have been taken at the state level aimed at shutting down Canadian pipelines that help meet critical American energy needs. Regardless of where one stands on the issue of fossil fuels, what has hurt the most in the conduct of American energy politics has been their failure to recognize and reward Canada for being a reliable supplier of energy in all forms to the American market.

The Canada-US relationship could be rocked by more uncertainty in the years ahead. The US is deeply divided and the partisan schism bedeviling its politics is profoundly worrying. This is bound to create problems for the Biden agenda. Trump’s grip on the Republican party remains and he is obviously campaigning to retake the presidency. The Republican party that we knew so well—conservative to moderate and sensibly engaged with the world—is no more. So, Canada and the world are faced with a significant number of Americans in both parties who have embraced nativism and economic nationalism. For America’s largest trading partner, this is not good news.

And in the broader North American context, the situation is doubly worrying. While for years I have been among Canadians advocating for constructive Mexican engagement in North American affairs, and have been privileged to work closely with four Mexican presidents, I am deeply concerned about the outlook for Mexico. It continues to be wracked by violence and drug warfare. In the recent mid-term elections, some 100 candidates were assassinated. Mexican President López Obrador, has embraced a statist and interventionist agenda. He has rolled back significant reforms, especially in the energy sector. Despite some minor setbacks in the midterms, he remains popular and a viable opposition alternative has yet to coalesce. He is not going to be looking north of the border for engagement.

How should Canada respond?

First and foremost, beyond pursuing bold domestic policy goals, re-setting our relationship with the US must be our highest strategic economic and security priority. The hard reality is that whether led by Democrats or Republicans, dealings with the Americans are going to be fraught with uncertainty and challenges. Relying on sentimentality and wishful thinking will not deliver the results we want. To begin with, we must double up on the resources we devote to pursuing our interests in Washington and at the state level. Building on the Biden-Trudeau relationship is vital. More than any prime minister, Mulroney wrote the book on how this should be done. Strengthening business-to-business ties in advancing mutually beneficial job and investment polices is crucial. And trade unions on both sides of the border have an incentive to join in common cause as both countries push for innovation-based job creation.

What are some of the concrete steps Canada should be taking? The number one priority, of course, is to emerge safely from the COVID crisis and open up the Canada-US border. Maximum cross-border coordination is key and given the stakes we cannot afford to bungle the job. Let me turn now to the new NAFTA—the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) which came into effect on July 1 last year. Its 16-year renewable status should evolve in favour of permanency, subject to amendment, of course. The new chapters of the agreement on digital trade, good regulatory practices, small and medium-sized enterprises and anti-corruption represent important steps forward. But trade agreements provide a framework for action and in my view too little so far has been done to take full advantage of the opportunities offered by CUSMA. Relying on “autopilot”, as we did with NAFTA, is no way to do business. We must face the reality that Mexico under the current administration is not as willing a player as are Canadians and Americans. This should not hold up progress. We should act where it is in our mutual interests to do so. To borrow an expression from SPP days, “three can talk and two can do”.

Beyond the CUSMA, how to proceed with the Americans?

My list is long but let me give you a few examples. We need to push hard on getting Canada within the Buy America provisions. Given our joint supply chains and joint procurement potential, this makes eminent sense. On cybersecurity, we need to harden the defences of our common infrastructure. On critical minerals, we need a bilateral strategy that will incentivize production and secure long-term supply and purchases. The potential of Canada-US cooperation on energy and the environment is endless. Clean energy technology cooperation offers multiple channels of opportunity. The electrification of the transportation industry is a case in point, where mutually dependent supply chains are at work. On defence and security, the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) needs modernizing and both countries need to take much more seriously both Russian and Chinese threats emerging in the Arctic. The cyber threat to continental industries and infrastructure is real and demands a joint response. Some of what I have mentioned is referenced in the “Roadmap for a Renewed US-Canada Partnership” agreed on by the prime minister and the president in February. My concern is that this wish list will simply fall by the wayside, particularly as the US seeks to come to terms with its other more urgent priorities. It’s up to Canada to keep these issues on the front burner.

How to deal with China is high on the agendas of both our countries. Arriving at a modus vivendi with China is the central challenge of our times. It’s an American challenge, it’s a Canadian challenge, it’s a global challenge. Since my days as a young speechwriter on Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s staff in the early 1970s, I have advocated for full and peaceful Chinese engagement in the world community. My assumption was that China would over time embrace Western-based concepts of the international liberal order and universally accepted principles of the rule of law. This has not happened. Under the leadership of Xi Jinping in particular, marked by “wolf warrior diplomacy”, we are witnessing a much more assertive China leaving no doubt as to its aspirations for global pre-eminence.

What does this entail for the Canada-US relationship? The subject requires deep introspection. China cannot be simply ignored. Canada, the US and democracies across the globe must work with China. Canadian differences with China on human rights and on the continuing baseless imprisonment of “the two Michaels”, Michael Kovric and Michael Spavor, must be negotiated. Canadian business and cultural links with China deserve to be preserved. But when it comes to vital strategic interests and the preservation of the liberal world order, Canada must ally itself firmly with the US and other democracies. We cannot have it both ways. Our American friends are watching carefully how we are playing our cards with China. Bottom line on this issue: if we play ball in an intelligent way with the Americans on China, it will serve our national interest.

Some final thoughts.

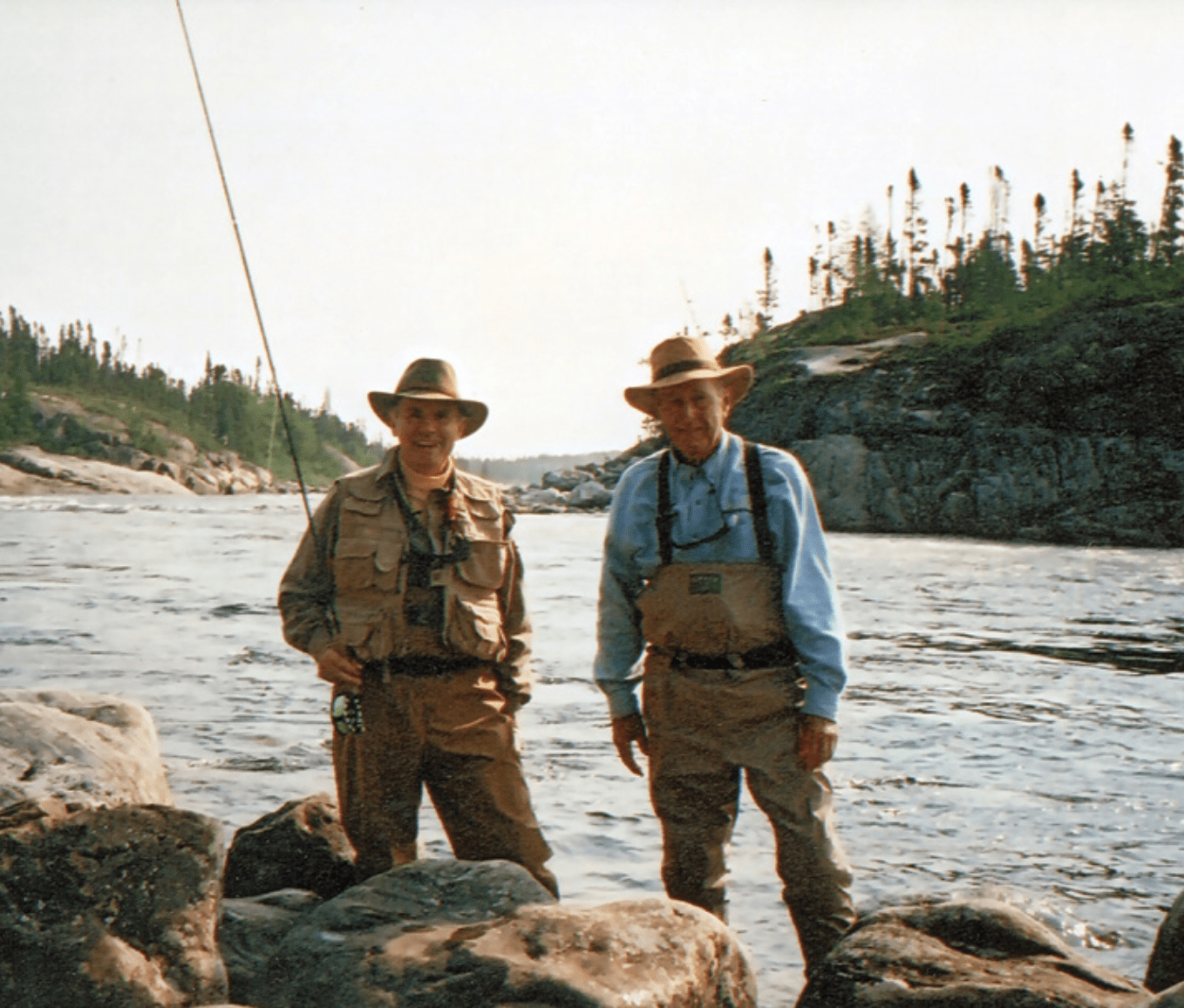

I have been a huge admirer of the Great Republic all my life. By the time I was in my teens, I had visited most of the 50 states of the Union. I played a private sector role in advancing the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement and the NAFTA. I have met every president since Richard Nixon (Trump excepted) and I’ve even had the pleasure of fly-fishing for salmon in Labrador with one of America’s great presidents, George H.W. Bush in the summer of 2003. Our two-way relationship is complex and whether it’s fully understood or not, we want to believe we are “closest allies and friends”. But we have to work harder at making this a reality. We can no longer afford to take each other for granted.

Given the global preoccupations of our neighbouring superpower, devoting serious and sustained attention to Canada is difficult. But on this score, I would offer some wise advice to our American friends. It comes from a dear friend and mentor to me, former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, one of America’s greatest statesmen. He said “good neighbours tend their gardens – they weed them and keep them in good order and don’t let them cause harm to that of their neighbour.”

Good advice indeed and equally applicable to Canada.

Thomas d’Aquino was the founding CEO of the Business Council of Canada, and is Canadian Chair of the North American Forum. He is also Chair of Thomas d’Aquino Capital, based in Ottawa.