Time for a Bilateral Reality Check

The CEO of the Canadian American Business Council writes that the bilateral relationship is literally at a crossroads in the aftermath of the Trump years and the global pandemic. “We need to revisit this partnership, and stop taking refuge in old, reliable platitudes” notes Maryscott Greenwood. “We have experienced a breakdown of the cooperative border management that has defined the relationship for decades.” Best friends and closest allies? We need a new frame of reference, she adds, suggesting that’s one urban legend in need of updating. She concludes: “We need to decide what is in our common interests and relentlessly pursue it.”

Maryscott Greenwood

So much of life is about managing expectations. Canada and the US have had a few seminal moments in recent years, and I would submit that it’s time our two countries recalibrate our expectations of one another. This way, we can minimize misunderstandings and disappointments, and maximize the crucial business of co-managing the most successful integrated economy in history.

To put it mildly, things have changed.

The lifetime event from which we are emerging seems to have re-ordered everything, including the relationship between Canada and the United States. Nobody planned it, but it happened. And common sense requires that our two countries reassess the way we deal with each other.

Since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020, governments have been beset by voters motivated by fear, anger, indignation and despair. Consent to govern was threatened. Science saved lives, but also complicated our economy with shifting obstacles and restrictions as it coped with and studied a virus capable of constant mutation.

Ultimately, because of our respective cultures, the United States and Canada dealt with the virus differently. Canadians, with their higher degree of social solidarity, were more inclined to accept lockdowns, mask mandates and other impositions. Americans’ emphasis on individual rights and personal freedoms led them down another path. And ultimately, that parting of ways set up what I would argue is a new paradigm for how Canada and the US deal with each other. We face a new reality in this old relationship, and there is likely no going back.

That is not to say Canada and the United States are no longer partners. Of course, we are. But a partnership can be anything from the keen ardour of an all-in, fully engaged collaboration to something more rote. Unfortunately, we are drifting toward rote. The old, reliable platitudes are no longer useful.

Let’s start with the greatest received truth of all—that Canada and the United States are best friends and closest allies. Canadians and Americans are the most relaxed of tourists in each other’s countries. They blend in effortlessly. We have a common language, and common cultural references. Yes, there have always been certain sharp differences—gun ownership and levels of religiosity, to name two—but our commonalities have always been overwhelming.

Canadian soldiers fought alongside American troops in both world wars, and nearly every conflict since, with the notable exception of Vietnam. We have a common aerospace defence organization, NORAD. We haven’t attacked one another in more than two centuries, since the War of 1812. We share secrets and technologies and supply chains. Our expectation of each other is that of best friends.

Look closer, though. Wide swaths of people on both sides of the border increasingly see the trade treaties that integrated our economies as a weakening of economic sovereignty, even an export of jobs. The success of economic integration in North America has become a political issue, animating the protectionist right and, yes, the protectionist left in Canada and the United States.

From 2017 until earlier this year, the US had an isolationist president who denounced what he called globalism and threatened to tear up NAFTA, calling it “the worst trade deal ever made.” Then he imposed tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum, actually citing those products as a threat to American national security. The tariffs were disruptive, and while they were ultimately dropped in the aftermath of the new North American agreement, to the immense relief of cross-border industries, Canadians reacted with disbelief. Canada, a threat to US security?

In point of fact, the 45th President merely confirmed what a lot of Canadians already believed about the US, and they began looking elsewhere in the world for partnerships. They talked more urgently about finding other allies. The Canadian government sought other trade agreements with Europe and Asia.

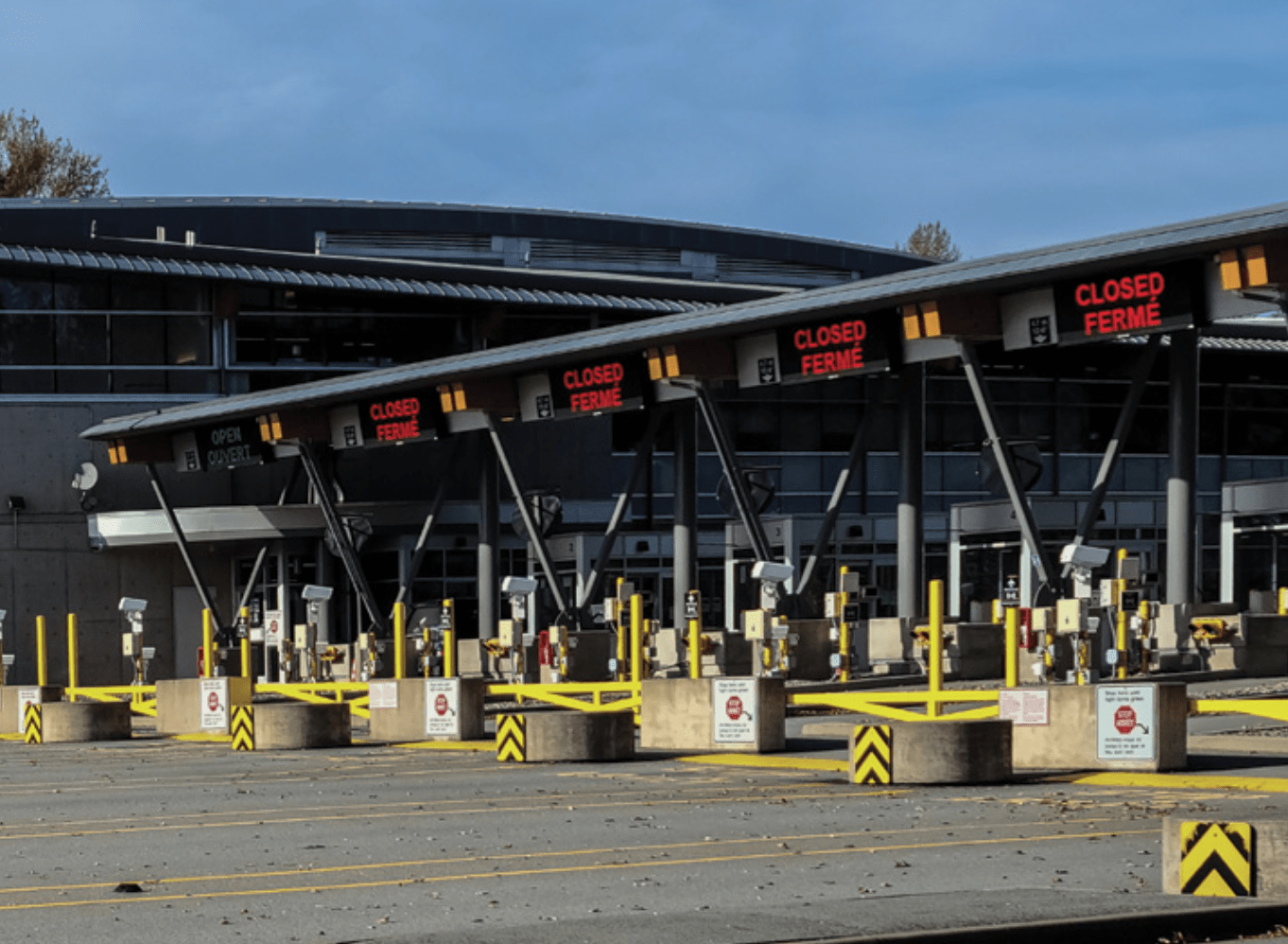

Add to that the pandemic, which resulted in a separation of the American and Canadian populaces that has never before occurred. Suddenly, to use a Canadian phrase, we were two solitudes—essential business did continue, but the gates of the land border swung shut. Most Americans, meaning populations not near the northern border or dependent on tourism, didn’t really notice at first. But Canadians did, and many of them approved of the new disengagement, at least in the beginning, given US infection and death rates several times higher than Canada’s COVID cases.

As vaccinations resulted in dramatically lower numbers in the spring of 2021, members of Congress began calling for a reopening of the border to discretionary travel. And by summer, Canadians became more supportive of re-opening the border to non-essential travel. But when Canada finally did agree to admit vaccinated Americans, the White House refused to reciprocate, citing concerns about new variants to the virus. In fact, at the time of this writing, the US government is talking about the Canadian border in the same terms as the Mexican border, despite dramatically different rates of vaccinations in the Canadian and Mexican population.

But back to Donald Trump for a moment. The truth is that Trumpism gave Canadians cover to speak aloud what many of them used to say only in private: that they don’t really like their neighbours to the south.

Canadians may still view economic cooperation as a necessity, but will they will reward leaders who seek ways to keep America at arm’s length? Close allies and best friends? Perhaps that was once the case, and may someday be again. Meantime, we should be clear eyed about how we view each other.

Another great received truth about the Canada-US relationship is that it ebbs and flows in direct proportion to the personal relationship between the president and the prime minister. Remember Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan? They were close, and the relationship prospered under their stewardship.

But let’s look dispassionately at the relationship since those days. Trump didn’t love Justin Trudeau. He insulted him publicly, tweeting from Air Force One that Trudeau was “weak & dishonest” in hosting the G7 summit at Charlevoix in 2018, which he had left on the pretext he had to fly to Singapore, and then instructed US officials not to sign the usual communique.

To be sure, Trudeau was in good company—Trump insulted other world leaders, even traditional allies. And yet, the US signed and ratified the updated version of NAFTA. Stephen Harper and Barack Obama were not particularly close, and yet their administrations greatly furthered regulatory cooperation. In February 2011, they signed Beyond the Border, a landmark joint security perimeter agreement, and they created the Regulatory Cooperation Council, two priorities of the CABC, as it happens.

Obama did have that short bromance with Trudeau in 2016. But it didn’t secure the Keystone XL pipeline extension for Canada. In fact, President Biden, another Trudeau admirer, nixed it on his first day in office.

Personal relationships between leaders are relevant, but to crib Henry Kissinger, who cribbed Charles de Gaulle, who cribbed Lord Palmerston: nations don’t have friends, they have interests.

And while I’m at it, let me debunk another axiomatic truth: our famously open, famously unguarded, famously long shared border. A 5,500-mile-long, cooperatively managed open door.

There’s nothing like it anywhere. That was somewhat true, once. But in the here and now, I’d characterize it as more of a stubborn legend. As I mentioned earlier, the land border was closed by mutual agreement in March 2020, but the Canadian and American approaches to one another immediately went asymmetrical.

The fact is, Canadians were free from day one of the pandemic to fly into US destinations. They were exempted from White House directives denying entry to much of the world’s population. They still are. Canadians were able to keep vacationing and visiting families and property in the US. Some of them were fully vaccinated in the United States early in 2021, when Canada was still waiting for vaccines.

American air travelers, meanwhile, were barred from entering Canada. When Ottawa finally decided to relax its strict quarantine rules for non-business travel, it continued to exclude even fully vaccinated Americans from visiting Canada. It took until mid-August of this year before Canada was willing to relax restrictions on non-essential air travel from the US.

What does that tell you? It tells me that Canadian voters like it that way. And let me note something else: The bilateral relationship has historically benefited from the idea of reciprocity. Unequal treatment sets the table for a host of policy “dislocations” that end up having real impact on real people in both countries.

As of now, strikingly different policies exist on either side of the border. The US has not defined a system for validating proof of vaccines. Canada has. How far that cleavage will go, and its consequences, is of great interest to those of us who champion the smooth functioning of the border. This much is clear: we are experiencing the breakdown of the cooperative border management that has defined the relationship for decades.

Anyone who doubts that need only consult the record of White House press briefings. Asked in July why the United States was leaving its land border to Canada closed after Canada announced it was reopening its side, President Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki said: “We take this incredibly seriously but … I wouldn’t look at it through a reciprocity intention.”

Another old standard worth questioning: Canadians treasure the bilateral relationship, while the US takes Canada for granted. The Canadian American Business Council (CABC) was fairly involved behind the scenes during the NAFTA renegotiation. We had a line of sight into why Congressional Democrats voted overwhelmingly in favour of what was after all a Trump economic package, approved by Congress in December 2019, even as they prepared to impeach him for the first time in January 2020.

It wasn’t simply because of Canada’s famous charm offensive, which absolutely happened, led by then-Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland. It was also because American business was horrified at the idea of tearing up NAFTA and retreating behind a tariff wall. No, Americans do not take the special relationship for granted. I would submit that Canadians have started to, though.

But it’s not helpful to identify problems without suggesting solutions. So let us propose a few. Instead of complaining about the inevitable “Buy America” clauses in American spending packages—and we don’t mean to minimize concerns about that—Canada could help its case by throwing in with the United States on something big and meaningful. For example, the Innovation and Competition Act, formerly known as Endless Frontiers. It’s a huge, bipartisan effort to compete with Chinese statism. It sinks more than $100 billion into artificial intelligence, semiconductors, quantum computing, biotechnology and advanced communications. China has denounced it as an example of Cold War prejudice, which says something in itself.

It is encouraging to see Canada already working closely with the United States to counter China’s effective monopoly on rare earths and other critical minerals. But a lot more needs to be done, and quickly. Electric vehicles will displace the internal combustion fleet, and those vehicles will need batteries, and those batteries will require critical minerals.

Or Canada could more formally lock arms with Washington on climate change policy, as the target for reducing carbon emissions is increased from the Paris Agreement of 2015 ahead of the next UN Conference of the Parties (COP 26) hosted by the British in Glasgow, Scotland this November.

On softwood lumber, a perennial bilateral sore point, we need to move beyond the spats and craft a permanent political agreement that benefits consumers as well as producers.

Counterintelligence should be expanded to counter new threats like those Russian hackers who clogged up the East Coast’s fuel supply this spring. Bring the full combined force of our militaries and cybersecurity experts to bear.

Let’s not keep up old pretenses. Let’s be mercilessly practical. We have nurtured and promoted tropes about ourselves that sound old and hackneyed to anyone who studies the relationship. We need a new, less sentimental analogy. We are not different branches of the same family tree or bickering siblings. We might not even be terribly special to one another.

If you think about it, President Kennedy’s assertions to the Canadian Parliament 60 years ago remain an objective truth. Economics has made us partners. And necessity has made us allies. We really don’t need a group hug. We need to decide what is in our common interest and pursue it.

Maryscott Greenwood is CEO of the Canadian American Business Council, and a partner with Crestview Strategy US in Washington DC. She previously served as a US diplomat posted in Ottawa.