A Key Pandemic Takeaway: The People Prevailed

Lisa Van Dusen

In 1984, in the days when authoritarian lunacy was either a fled nightmare or an ugly abstraction to residents of Western democracies, Václav Havel was asked to deliver a speech at the University of Toulouse. The Czechoslovakian playwright, who had been imprisoned multiple times for publicly advocating freedom and democracy, was — five years before becoming president of his country — nominally at large but living in a virtual prison of constant surveillance. Tom Stoppard, whose Czech roots and human rights activism had enriched his fellow-playwright friendship with Havel, delivered the speech “Politics and Conscience” on his behalf.

“I favor ‘antipolitical politics,’ that is, politics not as the technology of power and manipulation, of cybernetic rule over humans or as the art of the utilitarian, but politics as one of the ways of seeking and achieving meaningful lives, of protecting them and serving them,” imparted Stoppard—then at the height of his rock stardom as the British theatre’s verbal Jagger—in his role as Havel’s avatar. “I favor politics as practical morality, as service to the truth, as essentially human and humanly measured care for our fellow humans.”

The COVID-19 pandemic was born in the most dehumanizing chapter of global politics in more than half a century. The rantings of a treasonously weaponized American president, the chaos of Britain’s Brexit drama, the perpetual cortisol spike of social media wagging the dog of democracy and the fog of obfuscating nonsense fire-hosed daily into the content sphere to undermine that democracy had all taken a toll. Human beings, misrepresented by our loudest and most belligerent specimens, were suddenly brand-trending as reckless, gullible, corrupt, dishonest and infantile. Not in generations had such a significant swathe of politics seemed further from the ideal of “practical morality in service to the truth” that Havel espoused. In dystopian terms, replacing humans with robots had never seemed so alluring.

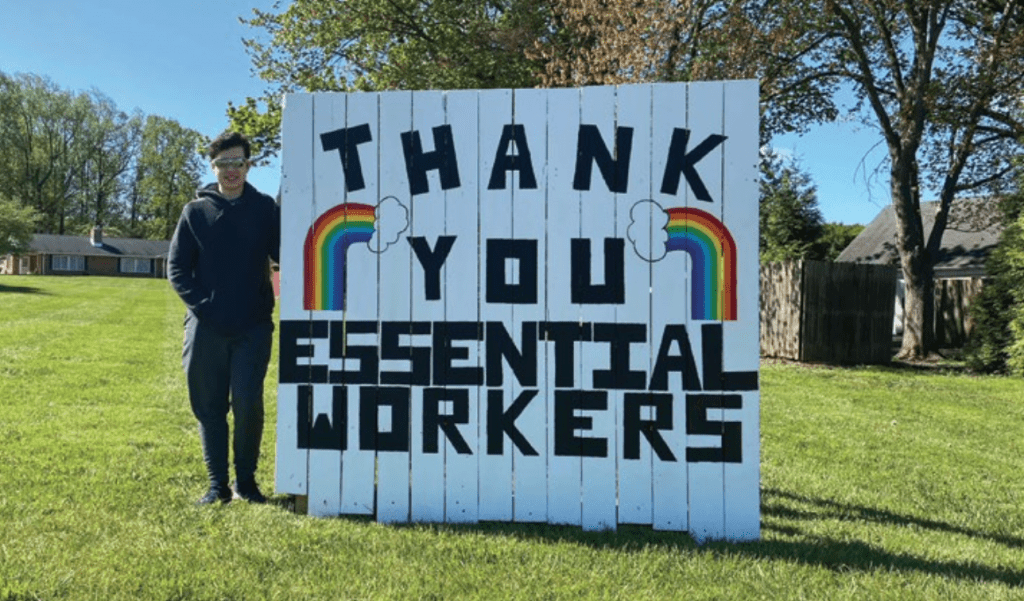

Of all the transformative impacts of this pandemic, the one that has struck most consistently and most indelibly has been the way in which human beings have risen to the moment. Overwhelmed by waves of the dead and dying, nurses, doctors, orderlies and EMT specialists set their fears aside to just keep doing what they do best to save as many souls as they could. Every day, the essential workers whose indispensability was suddenly so obvious kept showing up at cash registers, at prescription counters, in grocery stores…stocking aisles, driving trucks, maintaining utilities—keeping the world functioning in a crisis in ways that put the Davos men to shame.

People. People processed the daily changes in their context and adjusted—they carved out space to teach their children, to balance the books, to hunker down, to redefine their notions of urgency and mobility and necessity and luxury and boredom and patience. Yes, there were some who commodified stupidity and politicized division but most people masked up and adapted. We assessed the unexpected and evolving changes in our risk environments. We adjusted our priorities. We stopped caring about so many superficial questions whose importance had been shrunken by the stakes of our daily decisions about whether to stay or go, to improvise or forage, to sit or move. We started—per the cliché-for-a-reason—appreciating the little things.

We read and read, getting to know our local booksellers by email and drop-off. Some of us, for reasons whose origins remain a mystery, made sourdough bread—a lockdown fad my own brownie-baking habit never gatewayed into. We Netflixed and Primed and Google-Played our captive arses off until the only thing left to watch was Tiger King. We had “reach” dreams about not being able to hug our grown kids. Our untrimmed lockdown locks made Zoom galleries look like the Brady Bunch hippies episode.

The deaths—deaths of elderly people ending their lives alone and scared, deaths of health care workers in the line of duty, deaths of so many people who had so many better things to do—were devastating. The constant reminder of mortality, the ambient hypervigilance, grounded our perspective. Our new awareness of the fragility of life may not have produced a collective, existential epiphany that sent us all careening into the streets on Christmas Eve for an It’s a Wonderful Life appreciation jog down Main Street (“Merry Christmas, you crazy old Canadian Tire!”, “Joyeux Noël, Jean Coutu!!”), but it quietly sorted our values like a Marie Kondo home invasion.

Our American neighbours, perhaps in a more collective, existential epiphany for hitting in a presidential election year, chose a humanist, empathetic, competent, sane president. Life’s too precious to spend in the constant company of a lunatic, they seemed to be saying. The new president took office on a glorious day for poetry and prose, and in America, as in Canada, the vaccinations went up and the death count came down.

And social media evolved as a platform for a shared experience so real and so serious, it became a crisis utility and campfire. Doctors and nurses were now influencers, Anthony Fauci usurping Kim Kardashian. Authenticity overtook contrived perfection in Instagram posts, and toxicity was less ubiquitous. The absence of the man who had been, for four years, the provocateur, troller and Twitter IED-in-chief significantly reduced the profanity percentages. In a space where people were commiserating, sharing lockdown survival tips, seeking news and information amid life-and-death outcomes and, above all, grieving, reactive political fire seemed to recede.

Yes, the mass migration to online existence during lockdown held privacy and economic cautions. But we kept each other company—even when we didn’t know we were doing it. The fog of a bad day could be broken by a tweet of a new baby, a dancing child, any number of animal hijinks or a hilarious political one-liner; the pall of accumulated loneliness offset by a moment of appreciation for another human being in the next town or across the world sharing the pain of a heartbreaking loss, the architectural wonder of the perfect sandwich or a spectacular sunset. That seamless sense of community gave new meaning to the E.M. Forster exhortation to “only connect” because there wasn’t much else to do. Culture became group therapy. The strange intimacy of late-night show hosts working from home and interviewing unguarded, housebound celebrities made the bedtime ritual a morale-boosting public service, like a singalong in a bomb shelter.

Over a siege of more than a year, human beings proved both their compassion and their indomitability. They provided, in Václav Havel’s words, “human and humanly measured care” for their fellow humans, on and off-line.

Back in 1984, in the margins of the text of Havel’s speech, Tom Stoppard scrawled, “All political questions are moral questions.” Of course they are.

Lisa Van Dusen is Associate Editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.