Prince Philip’s Farewell

The Duke of Edinburgh’s funeral was a reminder of true love and epic perspective in difficult times.

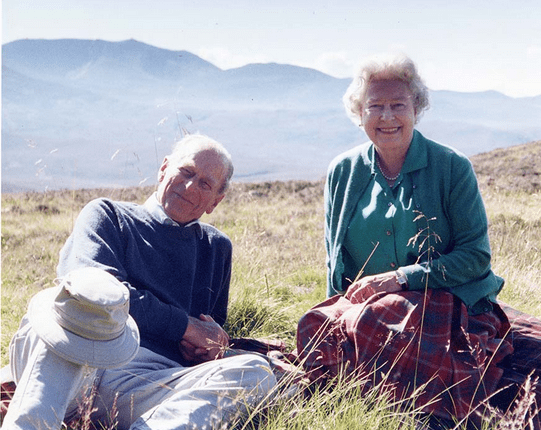

Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth II near Balmoral in 2003/Royal Family Instagram

Lisa Van Dusen

April 17, 2021

It was one of those sun-blasted British days that invariably remind you of how one day like this in England can make up for 100 rain-soaked ones.

The funeral of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh on Saturday at Windsor Castle’s St. George’s Chapel, carried both emotional poignancy and disproportionate symbolism as a nexus of some of the most consequential narratives of a consequential moment in history.

In emotional terms, first and foremost it provided the closing public moments of a love story that really began in 1939 with a 13-year-old girl besotted with a naval officer who made Ronald Colman look like Charles Laughton. The trajectory of their story, with its personal and historic inflection points, its adjustments and accommodations, through four children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren unspools in our heads like a Movietone newsreel of what was arguably the best personal and professional partnership the most important woman of the last century could have hoped for.

He was a flawed man of his time and the product of experience he clearly did his best to transcend — the pain of orphanhood channeled into physical strength and self-reliance at Gordonstoun; the natural advantage of his physical gifts obviated by valour in battle and intellectual rigour; the enormous privilege whose bubble he endeavoured to burst, with famously mixed results, in quip after quip.

But it was his relationship with the Queen that defined our relationship, as observers, with him. The arcane requirements of British royal marriages — biographical, psychological, temperamental, biological — especially of those undertaken by heirs apparent, have left a register of spousal calamities ranging from the luckless and headless wives of Henry VIII to more modern mismatches.

Philip Mountbatten — born Philip, Prince of Greece — was, by the age of majority, the ne plus ultra specimen of a particular class of 20th-century male, possessing all the qualities, skills and gifts that would have propelled him to a leadership role in the Royal Navy, in the City, as a diplomat, or at Westminster. That he also happened to be, as fate would have it, the “the only man I could ever love” in the words of the next monarch to her father, the King, presented a dilemma.

He was a flawed man of his time and the product of experience he clearly did his best to transcend — the pain of orphanhood channeled into physical strength and self-reliance at Gordonstoun; the natural advantage of his physical gifts obviated by valour in battle and intellectual rigour; the enormous privilege whose bubble he endeavoured to burst, with famously mixed results, in quip after quip.

For all its assumptions, dramatic extrapolations and factual liberties, even The Crown has never implied that the direction Philip chose at that juncture was driven by anything other than love on his part as well. Based on every overt indication, every historical account, he married Princess Elizabeth in 1947 despite, not because of, what her power and role would mean to his own life. It’s not hard to imagine the variety of ways in which her reign could have wobbled if he had been a different man, with a different sense of duty.

As former Governor General David Johnston has said since the Duke’s death, including in his fond eulogy during Saturday’s Canadian service at Christ Church Cathedral in Ottawa, Prince Philip was the embodiment of the notion of the “servant as leader” — servant leadership being defined by its original proponent, the late Robert Greenleaf, as altruistic service contributing to positive outcomes for a larger cause. It is characterized by the subsuming of one’s ego to that larger cause, and by loyalty to that cause being the default motivation informing one’s choice architecture.

In public terms, that approach to leadership was best captured by the sight so familiar to Canadians from the couple’s many royal tours, of the Prince, hands clasped behind his back, strolling the mandated two steps behind his wife, ever watchful, always having her back. In private, as accounts since his death have confirmed, it registered in decades of counsel that made him an asset, not just an appendage, to a Queen whose own intelligence and perspicacity have long been reported but who, like any sovereign, would have had few sources of advice whose loyalty was utterly unconditional and completely above question.

On Saturday in St. George’s Chapel, the importance of that bond was underscored by the sight of the Queen, newly widowed, sitting alone amid COVID social distancing rules — a choice also made, per The Independent’s reading, as a likely expression of solidarity with the public. The funeral and its farewell messages chosen by Philip — from the soaring Church of England hymns to the readings reflecting the Prince’s faith and values to the haunting beauty of a lone piper playing the Scottish threnody Flowers of the Forest, the lament for fallen soldiers of the Canadian Armed Forces — also filled the void left by so many funerals produced and prevented by the same virus. It was a moment matched by the rendition of Amazing Grace played for the Ottawa commemoration by Oakville’s Appleby College string ensemble.

At a time when so many elements of humanity’s status quo seem besieged by unmediated transformation, from our governance norms to our freedoms to our mobility to our economic prospects to our relationship with technology, Prince Philip’s funeral was also a reminder of what Britain’s royal family represents. With all of its institutional anachronisms, human drama and occasional melodrama, the royal family occupies a particular space in our current global narrative that represents history, continuity, faith, duty and, ironically enough, an incalculable source of soft power for a flagship democracy at a time when democracy everywhere is under attack.

And, on a human interest level, the patriarch whose integrity and values were being honoured would surely have approved of the sight of his grandsons leaving the church together. From the venue to the man remembered, it was a day for epic perspective.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor and deputy publisher of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.