Letter from London: Avoiding Austerity II in the EU

With Canada, the United States and other economies attempting to stimulate economic recovery while maintaining debt within sustainable levels, is the European Union on the same page with its 27 member countries? It’s about fiscal frameworks, striking the right balance and applying the lessons of recent history. From London, Jeremy Leonard and Angel Talavera of Oxford Economics provide insight.

Jeremy Leonard and Angel Talavera

Just as the fiscal wounds inflicted by the 2008-09 global financial crisis—and the European sovereign debt crisis that it triggered—had essentially healed, the coronavirus pandemic blew an even larger hole in European public finances. The total cost of the subsequent raft of furlough schemes, business grants, loan guarantees and other national and pan-EU fiscal support programs began to be measured in trillions rather than billions of euros even as tax revenue stagnated, and government deficits in eurozone countries reached 7½ percent of GDP last year, driving public debt to above 100 percent of GDP, forecast at this writing. With lockdowns persisting into 2021 and vaccine rollout stalled relative to the US and Canada, there’s a risk that the fiscal position isn’t likely to improve much this year.

Amid such big numbers, one might expect EU policy makers to set their sights on the tempting, but ultimately self-defeating, debt reduction “solution” of austerity once the economic recovery gets underway in earnest. That playbook guided the response to the global financial crisis a decade ago, ultimately resulting in slower economic growth in the countries that embraced it, which undermined the recovery and worsened the fiscal outlook.

Thankfully, it appears that the fiscal lessons of the sovereign debt crisis have been learned, as the focus of policy makers remains squarely on economic growth and recovery. Budget plans submitted by European national governments show that fiscal policymakers don’t intend on tightening prematurely, avoiding the errors of the sovereign debt crisis. Furthermore, governments have not hesitated to expand and extend the myriad pandemic support programs in response to the resurgence of the virus late last year.

Thankfully, it appears that the fiscal lessons of the sovereign debt crisis have been learned, as the focus of policy makers remains squarely on economic growth and recovery. Budget plans submitted by European national governments show that fiscal policymakers don’t intend on tightening prematurely, avoiding the errors of the sovereign debt crisis. Furthermore, governments have not hesitated to expand and extend the myriad pandemic support programs in response to the resurgence of the virus late last year.

Fiscal hawks might fret about sky-high debt levels when pushing for a quicker dialing back of fiscal stimulus, but the fact of the matter is that the eurozone isn’t on the brink of another sovereign debt crisis. The fiscal burden from additional stimulus amid a second wave looks manageable and we think concerns over debt sustainability are overblown.

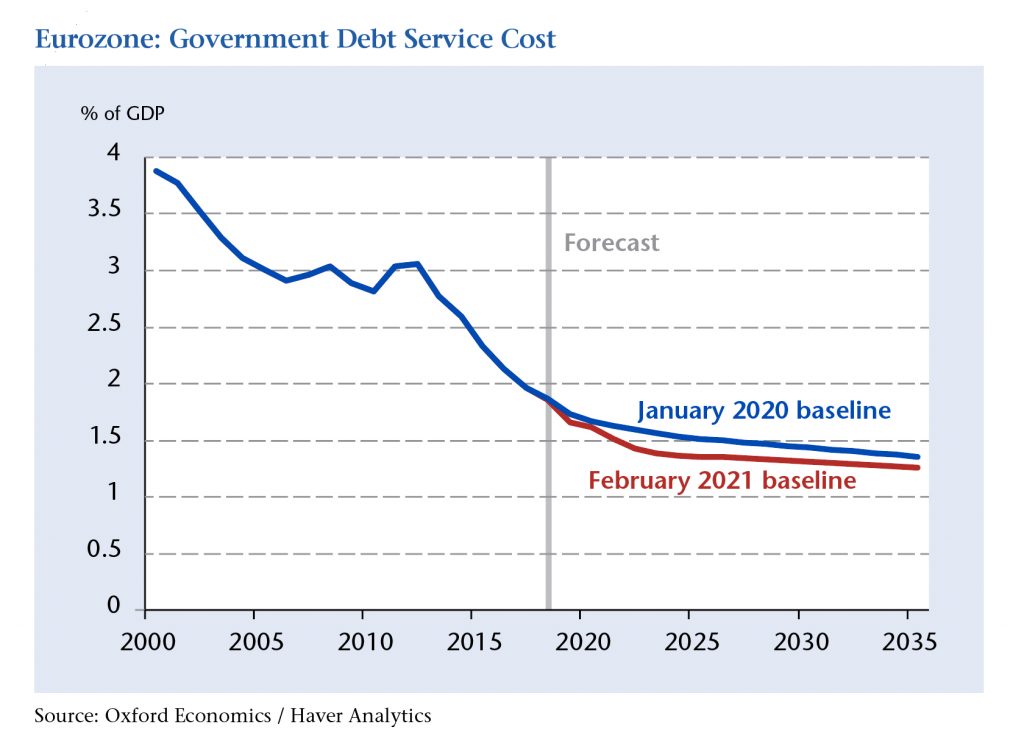

A far more relevant barometer of debt sustainability is the cost of servicing it, as it accounts for the level of interest rates. Debt servicing as a share of GDP has halved over the last two decades and we forecast it to remain much lower than over the last decade.

Even under a scenario of increasing long-term interest rates, debt levels look sustainable into the foreseeable future. Even if 10-year bond yields were to return to their pre-financial crisis level (due to, for example, a sharp increase in term premia akin to what happened following the global financial crisis), we find debt service cost as a share of GDP for the eurozone as a whole would remain roughly constant at its current rate of 1.6 percent for the indefinite future. The reason for this is that the effective interest rate on government debt is expected to remain at or below the rate of nominal GDP growth under plausible assumptions.

Even under a scenario of increasing long-term interest rates, debt levels look sustainable into the foreseeable future. Even if 10-year bond yields were to return to their pre-financial crisis level (due to, for example, a sharp increase in term premia akin to what happened following the global financial crisis), we find debt service cost as a share of GDP for the eurozone as a whole would remain roughly constant at its current rate of 1.6 percent for the indefinite future. The reason for this is that the effective interest rate on government debt is expected to remain at or below the rate of nominal GDP growth under plausible assumptions.

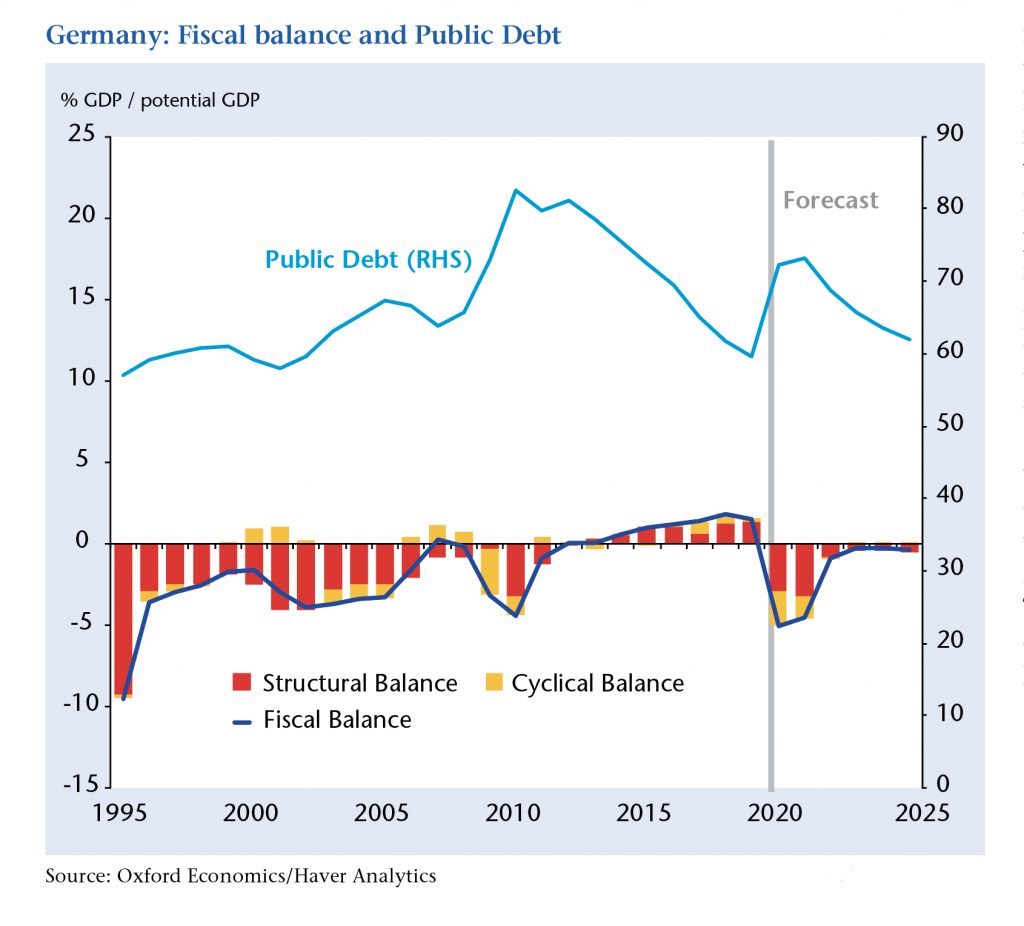

Also, a rise in interest rates now would still take years to fully translate into a higher cost of debt, as most countries typically finance public debt at long maturities. This mathematically means that the debt-to-GDP ratio can decline even in the context of small annual deficits, and it’s encouraging that Germany is expected to maintain modest fiscal stimulus over the next few years, in sharp contrast to the period following the global financial crisis.

Even though it is economically defensible (and advisable) to maintain a relatively loose fiscal policy over the next couple of years, EU fiscal rules could present a complication. These provisions of the EU Fiscal Stability Treaty that came into force in 2013 to pre-empt a future debt crisis such as the one that had just imperilled Greece’s eurozone membership—and made “Grexit” a word before “Brexit” was—are highly complex. Broadly speaking, they prescribe roughly balanced budgets in normal times with tougher targets for countries with higher public debt levels. While Germany may be able to comply with the rules again in 2022, other countries with higher debt burdens will find it challenging to revert to the EU fiscal rules. But if they succeeded, the bloc would face a potential repeat of the austerity mistakes following the global financial crisis. To avoid this, a change of the EU fiscal rules would make sense especially against the backdrop of low interest rates.

Of course, debt cannot grow indefinitely, but in the context of rock-bottom interest rates and continuing need for policy support amid an uncertain recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, there is no need to rush in reducing its size.

Jeremy Leonard and Angel Talavera are respectively Director of Global Industry Services and Head of European Economics at Oxford Economics, a global economic forecasting and advisory firm based in London. Leonard previously served as a research director at the Montreal-based Institute for Research on Public Policy.