It’s the Cruelty, Stupid: Beyond the Empathy Gap

What we’re witnessing in politics isn’t a passive dearth of empathy. It’s an active contagion of cruelty.

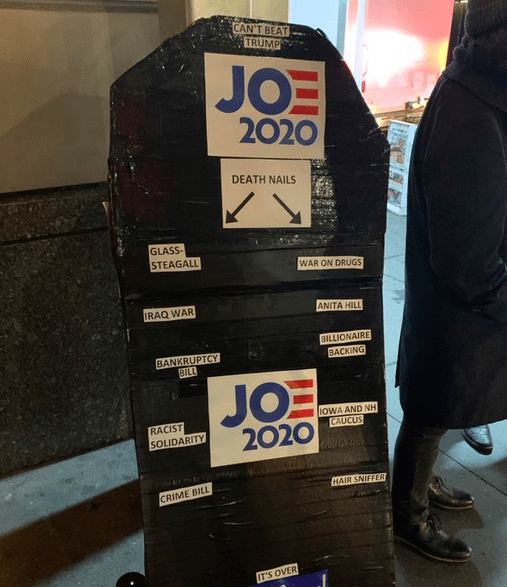

A coffin prop recently deployed at rally for Joe Biden, who lost a son and his first wife to an

automobile accident and another son to cancer

Lisa Van Dusen

February 20, 2020

The language of politics — at least in functioning democracies — tends to skirt the most negative manifestations of human psychology and behaviour. President Jimmy Carter was famously slammed for a 1977 televised address commonly referred to as “the malaise speech” during which he never actually uttered the word “malaise”. In an ironic echo of his controversial admission to Playboy of having committed imaginary adultery many times, just sounding like he was thinking about malaise got him into trouble.

Until Donald Trump made daily barrages of Twitter bile part of the political discourse, politicians generally tempered even talk about their opponents with euphemisms, qualifiers and rhetorical code. When they didn’t — when a candid, too-accurate-for-public-consumption crack was made about a political rival into a hot mic or to an unnamed source — it was considered a gaffe. An apology for the utterance if not the substance ensued, the opponent in question made as much of it as could be made without compounding the damage of a truth turned loose, and everyone moved on.

The evolution of political language toward casual and tactical cruelty has been lubricated by social media and enabled, in part, by the bizarre, unprecedented and, apparently, hermetically sealed viability bubble in which Trump operates, exotically unburdened by a fear of punishment either in the polls or at the polls, unrestrained by the usual invisible fencing of shame and consequence.

It also reflects a deeper, more serious trend. As with all lies delivered for propaganda purposes of cloaking, misrepresenting, misdirecting or falsely rationalizing, the new political lying tends to come with cargo that diverts from the substance of the lie and focuses our lizard brains on the cortisol-activating, viral impact of certain emotionally charged keywords of the kind Trump’s Twitter feed is littered with, including the seven dwarfs of presidential projection: ugly, fat, stupid, nut job, fake, weak and sleepy.

How Barack Obama or Ronald Reagan managed to run a superpower without ever using the words “shithole countries” to describe United Nations member states, “disgusting, rat and rodent-infested” (redundancy his) to describe Baltimore, or “Horseface” to describe the porn star to whom they paid hush money may have less to do with stylistic differences than with the larger content debris field informing why America’s superpower status is now up for debate.

Beyond the toxicity of Trump’s public pronouncements, including those that go out in his name on Twitter, there is a cruelty to his policy decisions — from the treatment of detainees at the U.S.-Mexico border to the ban on transgender military service to food stamp restrictions — that echoes a global trend in democracies being transformed by new world order norms.

Long before Trump generated the “children in cages” headlines that have overtaken the Statue of Liberty as the symbol of America’s treatment of immigrants and refugees, Australia implemented the pilot program for cruel and unusual punishment of migrants with its notorious immigration detention centres. The treatment and mistreatment of African migrants flooding Europe created a continental crisis that rationalized both Brexit and a wave of nativist populism. Trump’s targeting of individual journalists and the media in general as “enemies of the people” for doing their jobs is just a higher profile, belligerent soundtrack to the international trend of stalking, hacking, harassing and, in the ultimate, deterrent tour de force, decapitating of reporters for telling and reporting the truth.

What has been commonly described as a lack of empathy among leaders such as Trump, Boris Johnson, Jair Bolsonaro and other “disruptors” propelled to power on a tide of narrative engineering and corruption-for-power quid pro quos is far worse than that. In politics, a lack of empathy is an inability to identify with the people you serve, most effectively identified by actions rather than words. What is currently being perpetrated is a normalization of the kind of cruelty not seen in nominal democracies in generations.

For aspiring autocrats, cruelty serves a number of purposes. Cruelty, especially deployed in a public sphere where it was once anathema, destabilizes through the unfamiliarity of shock and revulsion. Delivered by people — including elected officials — who are supposed to care about your well-being, it wages psychological warfare by generating cognitive dissonance of the “this cannot be happening” variety. Politically, it can make change that is really a local variation on a global theme seem driven by personality rather than systemic design. Unchecked, it breeds distrust of institutions seen as powerless to stop it. It imbues observers with a sense of helplessness to inhibit resistance and action. For targets, it is meant to marginalize, isolate and neutralize through terror, disbelief and commodified schadenfreude.

In 2020, all of this can be done not only overtly by figures like Trump. It can also be done covertly, using the anonymity and undeclared affiliations of social media, and through proxies who generate content for interests wanting to own outcomes without owning their deplorable tactics.

As history has repeatedly shown, cruelty as a manifestation of weaponized evil — against critics, political rivals, witnesses, and scapegoats — is also the most cynical path to power for people too inherently unelectable to obtain it any other way. That’s not the only reason democracy has been hacked, but it’s an important one.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine and a columnist for The Hill Times. She was Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP in New York and UPI in Washington.