A Rare and Courageous Autobiography

Jagmeet Singh

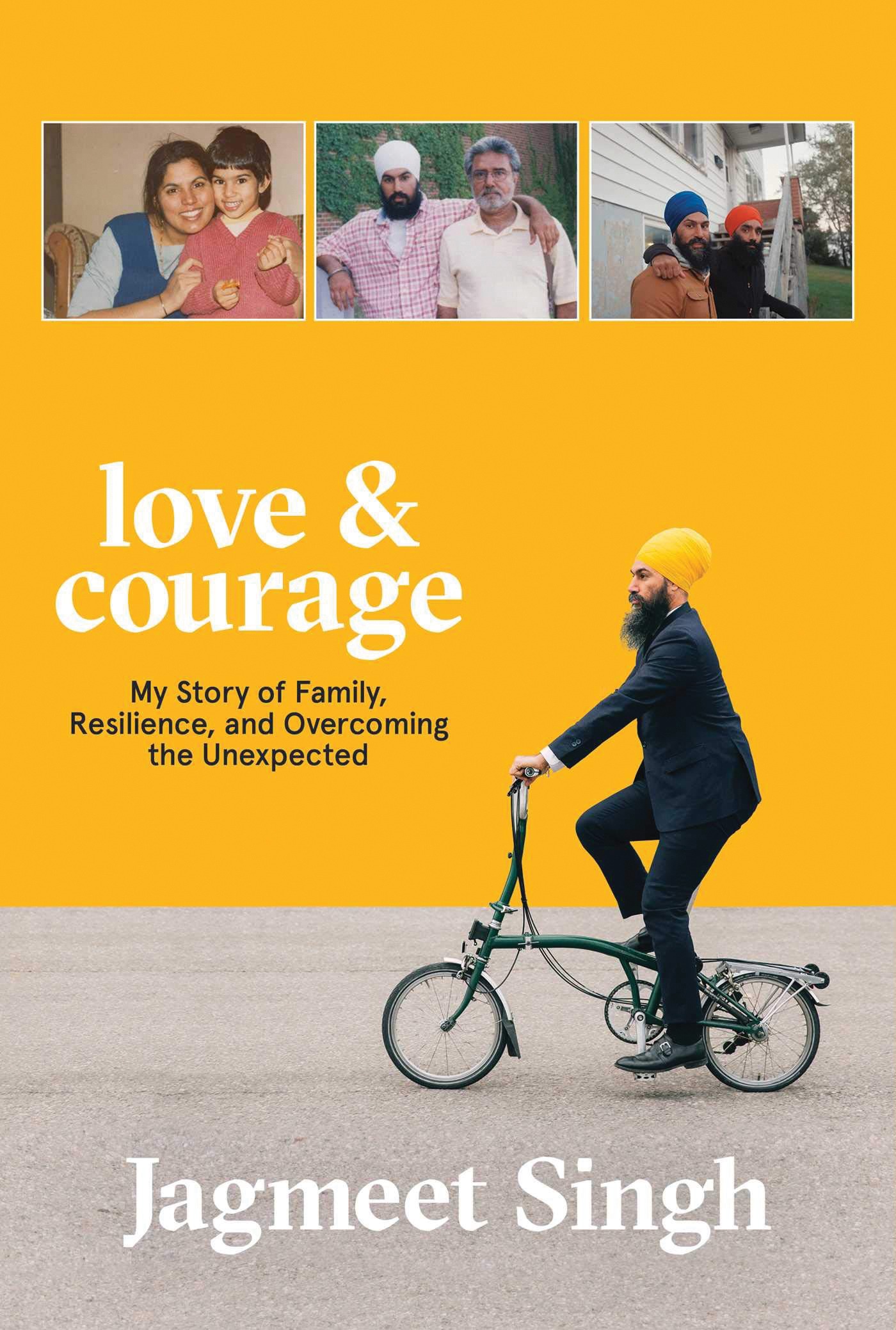

Love & Courage: My Story of Family, Resilience and Overcoming the Unexpected. Toronto.

Simon & Schuster Canada, 2019.

Review by Robin V. Sears

Having read too many pre-campaign memoirs to count over the years, I’m usually underwhelmed by them, especially by politicians’ autobiographies. Few of us are courageous enough to share with the world our faults, failings, humiliations and disasters. Never before have I read one that brought tears. Jagmeet Singh’s brave and candid account of his having survived and then blossomed out of a very tough childhood is that remarkable.

Having read too many pre-campaign memoirs to count over the years, I’m usually underwhelmed by them, especially by politicians’ autobiographies. Few of us are courageous enough to share with the world our faults, failings, humiliations and disasters. Never before have I read one that brought tears. Jagmeet Singh’s brave and candid account of his having survived and then blossomed out of a very tough childhood is that remarkable.

In the 1960s, Canadian immigration was tightly capped by nation of origin and therefore race. Before a merit-based system was introduced, there were years when we admitted more than 50,000 Europeans and fewer than 1000 Asians. Jagmeet Singh’s parents were the first-generation beneficiaries of a new vision of Canada.

As his impressive new biography makes clear, not all Canadians got the message. Racist taunts and schoolyard bullies were part of the lives of that first generation. Singh offers the best counsel possible that also precludes damage to victims: no matter how humiliating the insult, defend yourself, with your fists if necessary, but do not match hate for hate.

Singh could have produced just another narrative of the immigrant’s journey: the tough years of financial struggle, the families forced to live in different cities, the relentless determination of parents that their children excel at education, etc. There were three obstacles to the credibility of such a tale—sexual abuse, racism, and alcohol.

Singh takes special care to try to educate a reader oblivious to the tragic history of the Sikh community. He focuses especially on his generation, which grew up in the aftermath of the state-orchestrated massacre of Sikhs following Indira Ghandi’s assassination by her Sikh bodyguards in 1984-85, the 1985 Air India bombing by radical Sikhs, and the Sikh nationalist movement of that era.

His generation of the Sikh diaspora was unique to Canada; greater in number, per capita, than anywhere else. Sikh activists willing to advocate violence were also here—though in absolute numbers they were a tiny, embittered group. Canada was where their most spectacular crime was planned and carried out.

The murder of thousands of Sikhs, those who died under the machine guns of the Indian Army—first at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab and later across the sub-continent—left an indelible scar on Sikhs everywhere. In Canada, where the counter-attack was launched in June 1985 with the bombing of a Delhi-bound 747 that killed 329 people, the pain was especially acute. No matter how loudly the community leadership denounced the bombing, it didn’t erase the stain in the eyes of many Indo-Canadians, and among a large percentage of Canadians.

The Sikhs have never told the story of their denigration and persecution well. There has never been a Sikh emissary who transcended the community able to transmit to the world a countervailing account of what the community has endured. Sikhs were the largest contingent of non-European soldiers in the First World War, with a shocking rate of mortality. They were promised, but then cheated of, their own province in a newly independent India in 1947. The list of indignities they’ve suffered is very long.

That one of the world’s first anti-caste, anti-hierarchy, anti-patriarchy, socially and religiously tolerant religious faiths is today widely condemned as barbaric and terrorist is a deeply felt hurt. Traditional ‘Sikhi’ values and conduct are astonishingly liberal, given the rather different convictions of the Hindu and Muslim faiths they grew up among.

Jagmeet Singh’s parents, like many survivors, attempted to bury their pain, to refuse to be humiliated by the racist taunts and political insults hurled at them from the day of the Air-India crash until today. But like other survivors of systemic persecution, Sikh parents of their generation, wracked with anger and guilt, often passed their pain onto their children: with a denial of empathy or enforced silence, and sometimes alcohol and abuse.

Even as a teen, Jagmeet began to wrestle with a better way to help his community to move on. With his brothers, he organized discussion and commemoration events. Later as a politician, he fought—not entirely successfully—for wider and deeper Canadian understanding. Naively, he appeared at some events where he tried to convey his message, one that later was encapsulated as “love and courage,” not recognizing the impact of sharing a room with those offering a more violent vision of a Sikh future.

As a very green young political leader he has grown quickly. He can now put his community’s suffering within the context of the agonies still endured by too many indigenous Canadians, and other more recently arrived racialized groups. He appears to be embracing an ambitious message: “New Democrats’ values, and mine, are a message of inclusion—especially our advocacy for those who suffer from racism daily, the neglected and those left behind. Our commitment to courage in the face of injustice, and our love for even those who attack us, are the Canadian values.’ It is a foundation that makes even some traditional New Democrats uneasy.

He faces Liberals once again anointing themselves as the guarantor of those values, despite a shaky record in actually defending them. He faces two conservative parties openly flirting with race-whispering. Given his slow start as leader and with poll numbers still hovering in the teens, he risks little with a bold progressive message.

The first clue in his autobiography that this is where his journey might lead comes in accounts of schoolyard bullying and violence. From a determination to become tougher and stronger through martial arts and the ability to inflict pain and suffering on his attackers emerges a recognition that that journey leads only to anger and bitterness.

An ironic twist, one that he took many years to resolve, was that his martial arts guru, to whom he was devoted, was also his sexual abuser. The man who was to give him confidence instead instilled guilt, shame and self-doubt. Singh describes this humiliation with veiled deft strokes only, leaving a reader to fill in the awful blanks—and to be a little in awe of his ability to have survived it. Unlike the privileged childhoods of his competitors, by the time he was sixteen he had endured routine racist harassment, the enduring pain of sexual abuse and his father’s descent into alcoholism.

This led to abusive behaviour by his dad and the near collapse of the Singh family. He does not oversell his role in guiding the family through a long set of disasters. But his leadership is clear. He describes the struggle to help his father to finally win control of his addiction with restrained emotion. His father’s fight to win his way back to being a doctor, a father and a husband is nonetheless powerful.

As they emerge from the final meeting, having won the long battle to have his father’s psychiatrist licence restored, one can only imagine their sense of relief and regret. His father says, “Thank you for supporting me and the family for so long …I’m lucky to have any [time] left. I want you to make the most of yours…go live your life. I’ll take it from here.”

Liberated from this burden, following his first celebratory vacation alone, Jagmeet Singh does. He takes up the political torch at the behest of his brother who will not give up his determination it should be Jagmeet’s role.

What happens next is a fateful chapter for a leader about to enter his first national campaign. For Canada, too—and especially for the millions of racialized Canadians who will be watching intently.

We’re accustomed to hearing Americans regularly claim, often about some triumph over racist adversity, that this “could not have happened anywhere else on earth.” “Except maybe in Canada,” one is tempted to shout. It is, however, probably true to say that a second-generation Sikh could not have risen to the leadership of a national political party anywhere but here.

Campaigns matter, and the poll numbers are as volatile as we have ever seen. But where leadership is concerned, character matters most. On the strength of his autobiography, Singh has established himself as the winner of those stakes already.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, a Principal of the Earnscliffe Strategy Group, is a former National Director of the NDP during the Broadbent years.