Innovation Equations

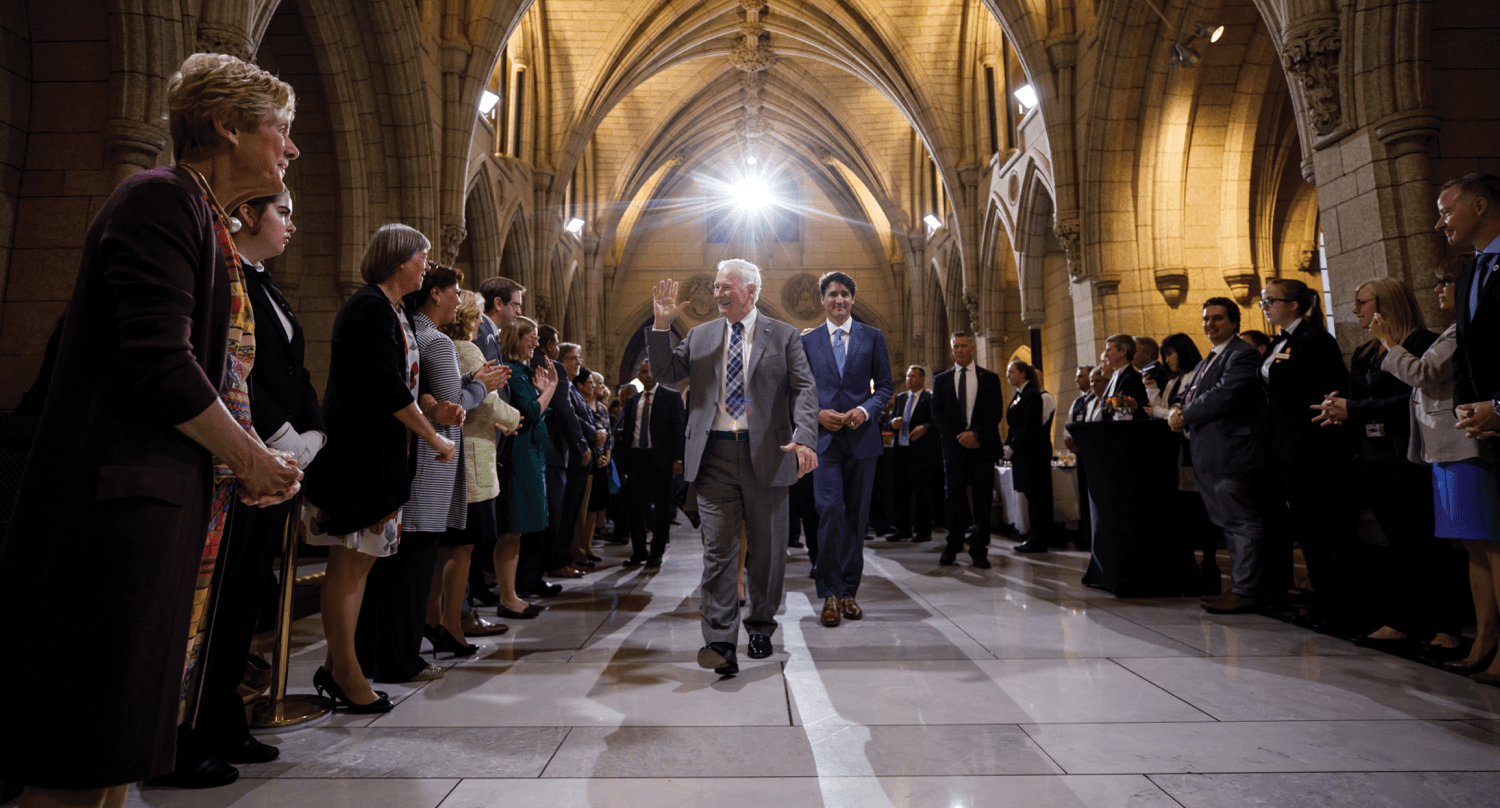

Part of Governor General David Johnston’s substantial legacy has been the way in which he has shared so much of what he learned in his vice regal role over seven years with Canadians and the world. Here, the man who launched the Rideau Hall Foundation to encourage Canadian innovation offers three prescriptions for businesspeople, policymakers and institutional leaders to move their organizations and our country from diversity to inclusion to a sustainable culture of innovation.

David Johnston

What image comes to mind when you read or hear the word innovation? Many of us conjure up the sight of person—usually a man. Perhaps he’s Leonardo sketching the blueprint for a flying machine. Or he’s Edison hunched over a workbench littered with tools, wires and gadgets. Or he’s Einstein seemingly lost in thought as he searches for fundamental truths about the elusive nature of the universe. Whoever he is, he is a solitary individual whose curiosity moves him to reject convention and conceive of a new way of thinking or acting that transforms our world forever.

Invention (from the Latin invenire, meaning coming in or arriving at), of the kind pursued by Leonardo, Edison and Einstein stimulates our senses because it expresses the bold, isolated search for truth that over the generations led to the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century and the birth of all the modern sciences. This singular focus on the workings of the solitary man’s mind has fed the conventional wisdom that the greatest advances in thought and method are taken only by an individual and only in isolation.

A true reading of history shows us that high and long leaps in thinking and acting occur most often when people of disparate backgrounds and knowledge combine their experiences and perspectives. That is why the word innovate is so helpful to our understanding of progress. To innovate (from the Latin innovare, meaning renew or alter) implies a deliberate change in the nature or fashion of something that exists already, precisely to make it of greater use to more people. By definition, innovation is a process by which people improve on existing knowledge or practice, and make it possible for that improved idea or thing to be used widely.

I have tagged that process the diplomacy of knowledge. Knowledge diplomats work across disciplinary boundaries, geographic barriers and political borders to uncover, share and refine knowledge. Thomas Jefferson’s brilliant metaphor of a burning candle is still, I think, the best way to illuminate the concept of the diplomacy of knowledge and its incredible power. The candle aflame symbolizes not only enlightenment but also the transmission of learning from one person or group of people to another. When I light my candle from the flame of yours, your light is not diminished. Just the opposite: the light from both shines brighter on all that surrounds us.

In physics, this light is called candlepower. By working across the borders that would keep us apart, we create the illumination necessary for innovation. The organizations, cities and regions where innovation occurs most often—think Bell Labs in suburban New Jersey, the city of Waterloo in south-western Ontario and Silicon Valley in northern California—are those where this light shines the brightest.

These centres of excellence remind us that diversity times collaboration equals inclusion.

The brilliance of these places is the result of diversity—of people equipped with a range of skills, knowledge and experiences coming together. In the case of Bell Labs, this diversity was largely disciplinary—physics, chemistry, engineering, mathematics, electronics, meteorology and metallurgy. In the Kitchener-Waterloo region and Silicon Valley, this diversity ranges beyond the sciences to include academics, entrepreneurs and investors. In each case, the critical mass of disciplines created not just an organization of innovation but a cultural dateline—a modern-day, innovation-driven equivalent of Renaissance Florence.

Yet diversity alone does not automatically lead to innovation. To put a finer point on it, diversity is not the same as inclusion. Inclusion comes when people from diverse perspectives collaborate to make meaningful decisions and take consequential actions. The plain truth is diversity alone is not enough to spur innovation. It is not enough for an organization, for instance, to be diverse and yet for that organization to exclude these diverse voices from contributing to the decisions and actions that count for most. Groups of diverse people must collaborate genuinely for inclusion and then for innovation to emerge. I would state the point even bolder: innovation is impossible, or at the very least unlikely, without inclusion.

Stated succinctly—inclusion times trust equals innovation.

Trust is the element that combines with inclusion to create innovation. In fact, trust is both an ingredient in and a by-product of inclusion. Workplaces, industries and economies rely on trust to make it possible for a diversity of people to collaborate openly, honestly and successfully. These same workplaces, industries and economies strengthen trust when they show they can go from having a diversity of faces to having the people behind these faces play important roles in decisions and actions.

Put in the context of real life, we build trust when we enable people to get up and dance (an invitation to action) and not when we summon them to the dance (an invitation to an occasion). My comparison to dance is literal as well as metaphorical. When I served as governor general, we at Rideau Hall made square dancing a central activity of the annual winter party for the diplomatic community in Ottawa. Square dancing may seem a little square to some, yet its gymnastics requires all those taking part to influence and own the experience as a group. In this case, this group of diplomats—representing a wide range of cultures—were not passive observers of a Canadian cultural custom. They took active—indeed, exuberant—roles in creating the entire experience. They were contributing to it, influencing it, owing it.

Square dancing is a good way to think of going from merely including a diverse group of people within an organization and economy, to having those in the group collaborate fully in the decisions and actions of the organization and economy. Another way of understanding the move from diversity to inclusion is to look at it as a progression from optics (a surface diversity of backgrounds and experiences), to outcomes (drawing on the knowledge and talent that stems from these diverse backgrounds and experiences), to ownership (using that greater performance to unleash individual creativity, deepen collaboration and spark innovation). Again, an essential ingredient in, and by-product of, inclusion is trust. Any decline or stagnation in trust has grave implications for innovation. When trust is shaken, individuals pull back, collaboration wanes, inclusion suffers and innovation contracts.

The importance of trust in galvanizing inclusion into innovation inspired me to explore the idea of trust more deeply. So much so that I wrote a book about it—titled, appropriately enough,

Trust. What I learned from that study is that Canadians can take steps to make our businesses, our institutions and ourselves more worthy of trust. These steps are really habits, attitudes and approaches, and my understanding of many of them stems from my experiences serving as the representative of the head of state in Canada for seven years. Some ways are individual—listen first, never manipulate, be consistent in public and private. Some are geared toward leaders at all levels and of all stripes—be barn-raisers, tell everyone your plans, depend on those around you. And some are societal—apologize, cherish teachers, invite others to dance.

This leads to a final mathematical formula: Innovation times intention equals a culture of innovation.

Identifying the habits, attitudes and approaches that build trust, and then acting in ways that exhibit them, is an example and expression of intent. The same principle applies to innovation. Identifying the factors that lead to innovation—diversity, collaboration, inclusion and trust—and then acting with intent to apply and strengthen them is vital to spurring innovation in Canada. Acting intentionally enables us to go from irregular instances of innovation to creating a permanent culture of innovation in Canada.

This emphasis on intention inspired the Rideau Hall Foundation to organize last year’s inaugural Canadian Innovation Week and to launch the Tech for Good Declaration. With this declaration, a person or organization pledges to live up to six principles when developing or adopting new technologies: build trust and respect people’s data; be transparent and give choice; reskill the future of work; leave no one behind; think inclusively at every stage; and participate in collaborative governance. When people and groups act consistently in these ways, they create a deep and sustainable culture of innovation not only in their organizations and institutions, but also in the country.

Rideau Hall Foundation’s current, intentional work to build this culture of innovation is to develop a Culture of Innovation Index. The index will give Canadians a baseline reference that reflects their willingness to be innovators, their awareness of and attitude toward Canadian innovations, and their understanding of financial and institutional supports for innovation. Equipped with this measure, Canadian organizations, institutions and policymakers can make intentional decisions and actions to innovate and, in doing so, expand and strengthen our country’s culture of innovation. We at the Rideau Hall Foundation just released the results of this work. Find them at www.canadianinnovationspace.ca/innovation-index.

Meanwhile, I urge businesspeople, policymakers and institutional leaders to follow these three equations. Apply them and do your part to move our country from being diverse to being inclusive, building trust and creating a sustainable culture of innovation.

David Johnston, C.C. served as the 28th Governor General of Canada and is Chair of the Rideau Hall Foundation.