Indigenous Child Welfare: Closing the Good Intentions Gap

Just days before newly-named Minister of Indigenous Services Seamus O’Regan unveiled the Trudeau government’s Indigenous child welfare legislation, Bill C-92, in late February, the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy produced its study on the same issue. The author of that study, Helaina Gaspard, writes that there’s room for improvement before the bill reaches royal assent.

Helaina Gaspard

Sound budgeting ensures that a country is fiscally solvent and on a sustainable track, aligns spending to declared priorities, and demonstrates results from previous spending. While the Trudeau government has increased both our debt load and program spending, Canada remains in a fiscally sustainable situation (barring major economic shocks).

For this government – especially its prime minister – rebuilding relationships with Canada’s Indigenous Peoples has been a defining priority. To this end, there have been several actions indicating an alignment of resources (both financial and human) to priorities. Consider, for instance, Budget 2019’s announced $4.5 billion over five years to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, the Indigenous languages bill, the talk of 10-year grants and new fiscal relationships with First Nations, investments in water infrastructure on-reserve and First Nations early learning and child care. But what about their results? Notwithstanding some significant efforts, progress towards better outcomes must lie ahead.

The recently tabled bill on First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families (bill C-92) is a step in the direction of change but falls short of a structural shift to alter incentives. The bill does recognize disparities in context and the need for a focus on prevention. It also recognizes jurisdiction for First Nations in child welfare as well as culturally-focused approaches to care for children in their home communities. But there are important gaps. The bill presupposes that funding relationships will be defined with exchanges between the responsible minister and communities seeking jurisdiction. Legislation guarantees a minimum standard. But while there is a requirement for negotiation, there is no clear indication of baseline components of funding, leaving the nature of committed resources up for debate. This offers the potential to negotiate resources to meet community needs but subject to political will and the capacity of the stakeholders negotiating both sides of the agreement. Beyond the allocation of resources, issues such as the duration of the agreement, mechanisms to account for adjustments such as population and inflation and reporting requirements, among others, would be issues to consider when negotiating.

Consistent with the government’s other well-intentioned actions on Indigenous affairs, C-92 contains insufficient linkage among investment, performance and outcomes. Current outcomes are all too well-known: Canada’s Indigenous Peoples have lower life expectancies, higher rates of infant mortality, suicide, chronic disease, alcohol and tobacco use, and also have lower rates of educational attainment and employment. Canada’s Indigenous population is young and fast growing. First Nations populations on-reserve are also projected to grow into the next decade. How will Canada and Indigenous Peoples measure well-being?

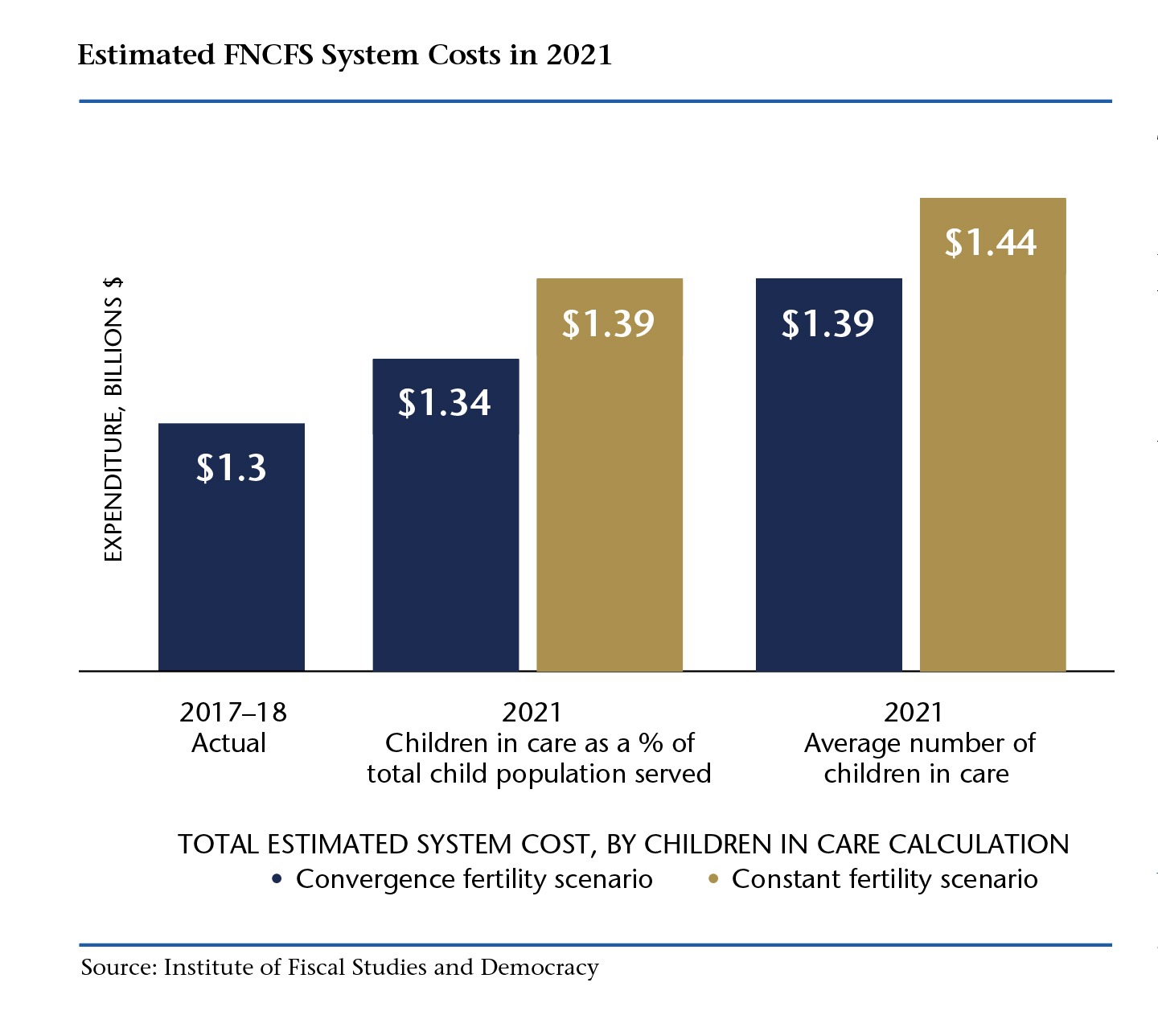

Following the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal’s (CHRT) rulings that found the federal government’s approach to Indigenous child welfare to be discriminatory, the issue has benefitted from greater investment and attention. The Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD) released its report on First Nations child welfare (undertaken at the request of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), the National Advisory Committee (NAC) and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society), in response to elements of the CHRT’s 2018 ruling. The bottom line of IFSD’s report is that the cost of the program is growing but it’s not delivering results for children. IFSD estimates that current spending on First Nations child and family services (FNCFS) is $1.3 billion. Under a no-policy change assumption, inflation and population alone would drive a total system cost increase of between $40 million and $140 million by 2021, depending on the population scenario assumptions used. To address underlying challenges, structural change is needed.

A program that focuses on results for children is within reach, but it’s not about throwing money at a problem. In Budget 2016, $634.8 million over five years was committed to the reform and strengthening of the FNCFS program and an additional $1.4 billion was committed in Budget 2018 over six years. The FNCFS program is currently being funded at its actual cost, although this is meant to be a temporary measure until the federal government reforms the funding structure (note: Budget 2019 funded Jordan’s Principle at $1.4 billion over five years, but did not announce new funding for FNCFS). Yet, the number of children in care grows, with a system designed to incentivize the placement of children in care to unlock funding. There can be no expected change in results without a structural change to the way the program is funded.

There are three things the government can do to make meaningful structural change, designed for progress. First, connect funding to outcomes. If the goal of the FNCFS program is thriving children, allocate funding in blocks to agencies and communities so that they can respond to the needs of the people. Block funding also requires accountability for all stakeholders (government, agencies and communities) to report on and deliver results.

Second, measure what matters and be comfortable adjusting in real-time. Thriving children means considering a holistic picture of their health and well-being. Indicators such as achieving age-appropriate development targets, learning Indigenous languages, having access to community programming, and a sense of belonging are examples of what should be measured to better understand how children are really doing and the results existing programs are generating. There should be annual reports to show progress; a five-year reporting requirement is too far into the future to make a difference. To get it right, there should be flexibility to determine what indicators matter and whether they’re useful.

Third, recognize that challenges in FNCFS are connected to a host of contextual factors such as poverty, unemployment and housing that won’t vanish in a generation. Different communities will have different points of departure. Instead of a single approach, meet stakeholders where they are and work with them to move ahead.

Budgeting in public finance is about more than adding and subtracting; it’s about setting a course for action and outcomes. The current government has framed its approach and stated its priorities, they now have an opportunity to demonstrate how they can deliver results.

Helaina Gaspard is director, governance and institutions for the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD)