Walking on the Razor’s Edge

Trade negotiations tend to be a proxy process for the bilateral relationship status of the parties at the table. In the case of trade negotiations during the tenure of Donald Trump as president of the United States, that dynamic assumes a whole new level of delicacy. As the Munk School’s Drew Fagan writes, the completion of the USMCA negotiations offers some insight into the state of our most important bilateral relationship in a time of tension.

Drew Fagan

On the shores of Lake Ontario, at the still-operating Cameco Corp. plant in Port Hope, uranium was processed for the United States Army and used in the world’s first atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and brought an end to the Second World War.

It seems strangely appropriate, then—if wildly disconcerting—that the Trump administration recently initiated a trade investigation of uranium imports on the grounds of national security under Section 232 of U.S. trade law. President Donald Trump seems determined to undermine the post-war Western architecture of open trade and multilateral security with his America First approach. So why not take issue with the very imports that helped end the war and launch almost 75 years of peace and prosperity; material that now fuels nuclear reactors?

In a recent conversation, Allan Gotlieb—Canada’s ambassador to the U.S. during the free trade negotiations of the 1980s—expressed shock at the recent NAFTA talks, especially the vilification of Canada: “It’s almost impossible to imagine. Since we emerged from the British Empire, our assumption always was that we were the United States’ best friend. I’m astonished.”

The impact of the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement deserves to be measured from two perspectives: by looking at the deal itself on the narrow grounds of trade and investment and by looking at the impact on Canada-U.S. relations more broadly.

On the first measure, all the sturm und drang of the negotiations appears to amount to relatively little. The deal is not ideal, certainly. The USMCA represents a limited turn toward mercantilism with an export ceiling on autos (second only to energy by value of Canadian exports to the U.S.) and the maintenance of “Buy America” programs. But NAFTA needed to be updated for the digital age and the new pact does so to some extent. Canadian consumers will benefit from a small opening of the domestic dairy industry to U.S. competition and a small increase in the import limits on duty-free goods. Canada’s cultural protections were maintained, although those terms have never really been inviolate. And the dispute settlement mechanism—which was a Canadian “red line” during the talks 30 years ago and remained so this year—was maintained, representing for Ottawa the preservation of rules over power in an asymmetrical bilateral relationship.

On the deal itself, the doctor’s creed seems to apply: First, do no harm.

But on the second measure, the broader state of Canada-U.S. relations, much appears different and not for the better.

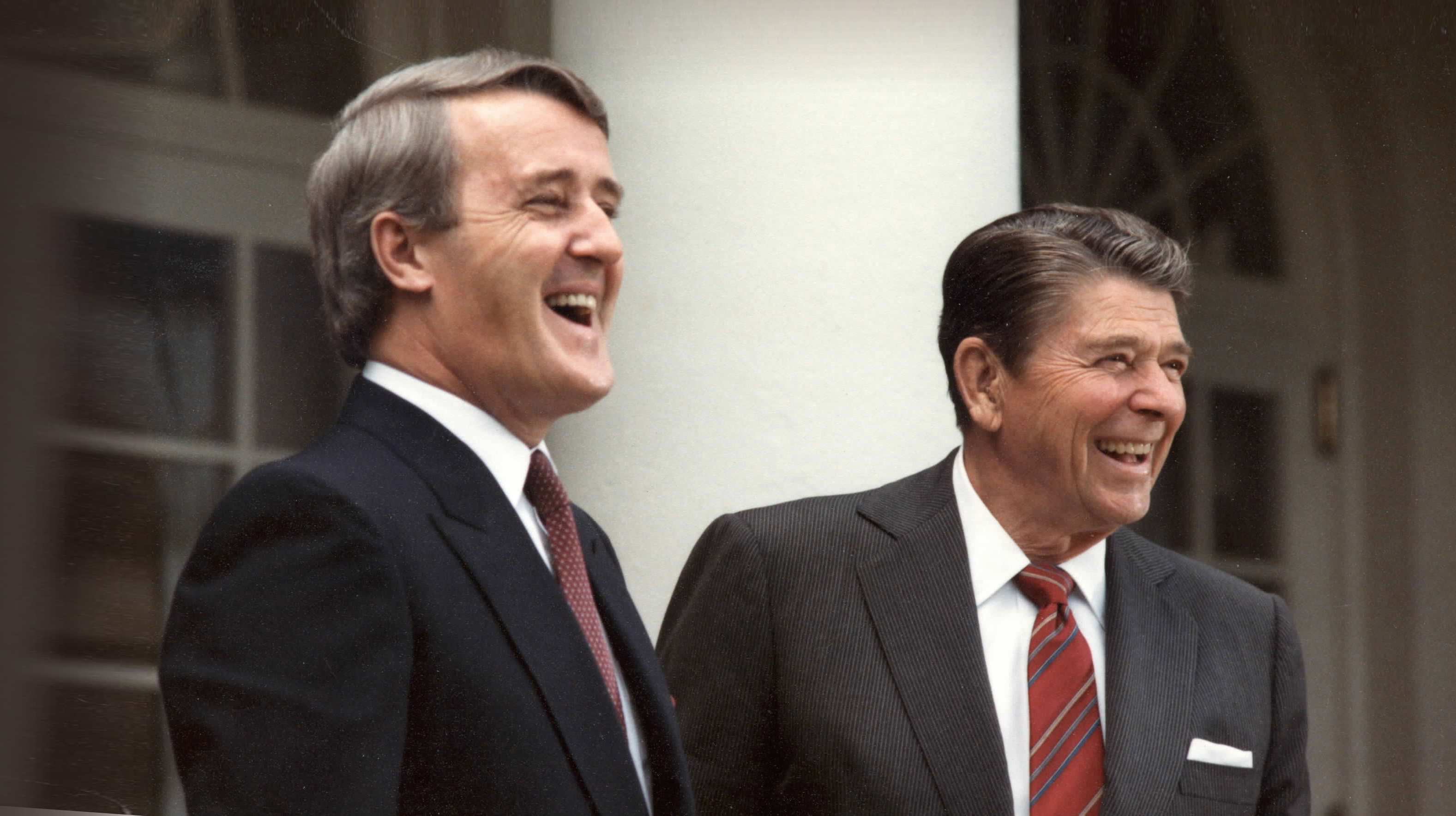

During a recent TV interview with President Trump, attentive viewers noted in the White House background a kitschy painting of an idealized scene of Republican presidents from Lincoln to Trump relaxing together as if at a public gathering. The two presidents sitting closest to President Trump were presidents Eisenhower and Reagan. Eisenhower’s own view of relations with Canada was remarkable given President Trump’s perspective: The two countries were so close, Eisenhower once said, that U.S. officials should see the issues as much from the Canadian viewpoint as the American. Reagan wasn’t quite so magnanimous but he found it hard to say no to Canada, especially when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney called.

With President Trump, Canadians are faced with an unprecedented challenge: someone who actually portrays the U.S. as having been victimized by what he characterizes as Canada’s guile (sharp trading practices) and sloth (security free-riding). Blame Canada—the two-decades old Oscar-nominated song—was meant to be satire. “We must blame them and cause a fuss before someone thinks of blaming us,” was the final line.

Perhaps we should have seen this coming. The salad days of free trade occurred in the early years. Trade with the U.S.—in both directions—grew at double-digit rates through the 1990s. Canada’s so-called trade “dependence” on the U.S. grew substantially so that by the turn of the century about 85 per cent of everything Canada shipped beyond its borders went directly south.

Then, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 occurred and nothing has been the same since. Bilateral trade growth slowed markedly as the border thickened and the North American economy went into recession. Meanwhile, China joined the World Trade Organization and the benefits of trade in the American mind—even with Canada—got lost to the controversies over outsourcing and deindustrialization.

Like the border impact post-9/11, the promiscuous use or threatened use of Section 232 trade remedies wasn’t considered a serious prospect by Canadian officials as far back as the free trade negotiations of the mid-eighties. Now, Section 232 must be considered a fundamental threat to Canada’s economic security and to its ties with the U.S. Canada did win terms in the USMCA for a 60-day cooling off period when the U.S. threatens to impose new section 232 measures but it remains to be seen whether this will be effective.

More broadly, the years ahead may seem like walking on the razor’s edge. We must maintain trade with Washington as best we can, for that is where the motherlode remains. (Canadian exports to the U.S. approach the total value of all interprovincial trade and are almost 20 times greater than exports to China.) But we must also build our trade and foreign relations elsewhere in the face of a powerful neighbour with an indifferent or even unfriendly mindset. This will be made more complicated still because the neighbour also is jealous—witness the terms of the USMCA requiring close consultation among the three members if any chooses to push ahead with a trade pact with a non-market economy such as China. The Trudeau government will soon test those terms, given China’s interest in re-engaging on trade negotiations.

“Developing our own distinctive international outlook while managing our all-pervasive bilateral relationship with the United States are but two dimensions of a single preoccupation that has dominated our existence for half a century,” Allan Gotlieb said in a speech to Ottawa diplomats in 1991 that deserves to be dusted off today. “Our overriding national preoccupation has been about how to limit U.S. power over our national destiny while deriving maximum advantage from our propinquity.”

In that speech and more recent essays, Gotlieb made a distinction between Canada’s multilateral vocation during the post-war years versus more recent times, which applies today as the Trump administration oscillates between retreat from the world and sabre rattling with friend and foe alike. Canada’s multilateral activism in the late 40s and 50s—the golden years of Canadian diplomacy—wasn’t aimed at drawing distinctions with the United States, as occurred more commonly towards the end of the Cold War and in its aftermath. Quite the opposite, it was aimed at helping give birth to and make effective the global organizations—the United Nations, the Bretton Woods institutions, NATO—that kept the United States engaged globally and prevented an American return to the isolationism of the pre-war years.

And so it should be today. No grandstanding or public piety, for this needlessly riles Washington. Just the dogged work that Canada excelled at two generations ago when the modern world was created. One timely example is Canada’s leadership working with like-minded countries—absent the United States—on WTO reforms to make it more efficient, effective and fair. What could be more worthy?

Drew Fagan is a professor at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, University of Toronto, and a Public Policy Forum fellow. He is a former Ontario deputy minister and head of policy planning at what is now Global Affairs Canada.