Why Superclusters Matter

Kevin Lynch

In its 2017 budget, the Trudeau government announced $950 million in funding for regional innovation superclusters. The five submissions that were chosen and unveiled in February represent a combination of technology-enhanced modernization of Canada’s legacy natural resource sectors and doubling down on 21st-century tech wizardry. Former Clerk of the Privy Council and current BMO Financial Group Vice Chair Kevin Lynch, an early supercluster advocate, writes that the sectoral innovation hubs will change Canada’s industrial landscape.

What a difference a revolution makes. Ten years ago, there was no public awareness of AI (artificial intelligence), machine learning or big data; today, these and other new technologies dominate popular culture as well as business strategy. Ten years ago, info-tech companies like Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Alibaba, Tencent and Google were fast-charging start-ups; today, they are among the most valuable companies in the world. What they all have in common are hugely scale-able technology platforms, an extraordinary capacity to gather, process and monetize data, and a willingness to flout traditional business models.

While identifying the precise characteristics required to become a tech gazelle is the dream of every business school professor, most successful tech firms share a number of common features revolving around “mind and place.” Despite existing in a digital, hyperconnected world of their own creation, tech companies, somewhat paradoxically, tend to originate from, and congregate in clusters. Why?

Such clusters are where talent gathers, where emerging technologies and ideas intermingle, where capital locates, and where interconnectedness is a public good. Part of the uniqueness of the fourth industrial revolution—internet-enabled technological change—encourages clusters. Tech firms are not monolithic in their technologies—they are continually developing or absorbing or combining new technologies to enhance their business models. Proximity to leading edge research, technology innovations and the talent that understands how to apply and manipulate them is crucial for tech competitiveness and growth.

Clusters have always been around, whether it was medieval European guilds, Victorian cities of the first industrial revolution, postwar global financial centres in London and New York, transportation hubs around the world, manufacturing centres in many countries, back-office information services in Bangalore and, of course, Silicon Valley.

What is different about today’s clusters is that they are technology-based not-

industry based, and that they exhibit increasing returns to scale, not diminishing ones. These properties give rise to technology superclusters, of which Silicon Valley is both iconic and illustrative. Superclusters exhibit extreme density in a certain range of technologies. This density of talent, technology, ideas, entrepreneurship and capital itself creates externalities for start-ups, scale-ups and titans operating within the supercluster. Evidence from examining performance metrics across clusters demonstrates there are disproportional commercial rewards to being part of the largest of the innovation ecosystems. Density matters.

The most comprehensive global ranking of innovation ecosystems is by Start-up Genome. Their 2017 rankings (Figure 1) indicate that Canada has two innovation ecosystems among the global elite, with Vancouver at #15 and Toronto-Waterloo at #16, but none among the top 10 superclusters.

The dynamics among the rankings are noteworthy. China has come from nowhere to have two ecosystems among the global top 10, supporting the Government of China’s Strategy 2025 to be a world leader in a specific range of technologies. Tel Aviv demonstrates you don’t have to be a global economic behemoth to create a top 10 innovation ecosystem, but you do have to have a clear strategy and strong leadership. After lagging, London, Berlin and New York City have surged in the recent rankings, suggesting that size alone does not beget innovation ecosystem success, but one wonders what Brexit will do to London’s attractiveness. Canada has demonstrated the ability to create globally competitive innovation ecosystems, but can it “own the podium” by building a top tier supercluster with all the spin-off benefits that accrue?

The Trudeau government’s “supercluster initiative” is designed to both broaden the range of technology clusters in Canada and deepen their capacity. It is expressly industry-led to emphasize applied technology innovations with early commercial applications, rather than university anchored research consortia.

The five chosen superclusters demonstrate both technological and geographic breadth: Ocean Supercluster in Halifax and St. John’s; AI-Powered Supply Chains Supercluster based in Montreal; Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster in the Toronto-Waterloo corridor; Protein Innovations Supercluster in the Regina-Saskatoon corridor; and, the Digital Technology Supercluster based in Vancouver. They will receive $950 million of federal funding over five years, to be matched at least dollar-for-dollar with funding from each supercluster consortia. To varying degrees, they will develop advanced technology applications to strengthen the competitiveness of Canada’s natural resource sectors, which is certainly needed. To varying degrees as well, they will enable technology diffusion into the broader SME business community, which is desperately needed.

What are the factors that will shape the success of the five nascent technology superclusters? First and foremost, it will be governance, not technology. The potential strength of the superclusters is their unique, business-led coalition of international companies, Canadian SMEs, tech start-ups, incubators and university researchers. The challenge is getting the proper governance around partner responsibilities and accountabilities, around ownership and decision rights, around allocation of funding to projects and around ambition for the supercluster—setting the key performance indicators (KPI) for success.

Second, it will be finding the right balance between the public interest and the private interest. The supercluster concept is based on externalities—that the whole is much greater than the sum of the parts—and that is the rationale for the public contribution. The partners will need to develop the public tech space, particularly for SMEs and innovation diffusion, not just their enhanced private tech space as firms. Third, and somewhat related, it will be finding the right balance between a cluster of projects and a cluster of firms. While projects will be the modalities, they are a means to the broader objective of a deeper cluster with more firms, more talent, more tech diffusion, more intellectual property, and so on.

Fourth, it will be building a collective brand for the supercluster, and this will require active marketing and brand development rather than following a passive approach. The payoff to an enhanced global tech and innovation brand is huge through attracting venture capital, global talent, global tech firms and researchers and entrepreneurs.

Fifth, it will be the ability to create a defining culture for the cluster. Why such an emphasis on culture in the building-out of the superclusters? I believe that a pervasive culture of innovation is essential for strong and sustained innovation success in all sectors of the economy and society—it is much more powerful than tweaking tax credits or fiddling with the terms of grant programs. It means a community where participants answer positively to cultural attributes such as: Does the cluster celebrate ideas? Does it mobilize diversity? Does it fuel innovation passion? Does it foster autonomy over hierarchy? Does it support failing forward? Does it listen hard and keep minds open? Does it think small and scale big? What entrepreneurs describe as most unique, and personally important, about top-tier innovation ecosystems besides their density and depth is their culture.

Lou Gerstner, the legendary CEO of IBM, observed in his autobiography: “I came to see, in my time at IBM, that culture isn’t one aspect of the game, it is the game—whether in business, government, education, healthcare or any area of human endeavor.”

While the superclusters will unambiguously better position Canada for the world of the fourth industrial revolution, we have to understand much more clearly and strategically as business, government and educators the extent of the tech transformations underway and their implications for both the Canadian economy and society.

The mass diffusion of digital technology and the rise of AI-enhanced automation pose adjustment challenges for all economies, particularly on the jobs and equality fronts. According to a recent Brookings report: “The digitization of everything has at once increased the potential of individuals, firms, and society while also contributing to a series of troubling inequalities, such as worker pay disparities across many demographics, and the divergence of metropolitan outcomes.”

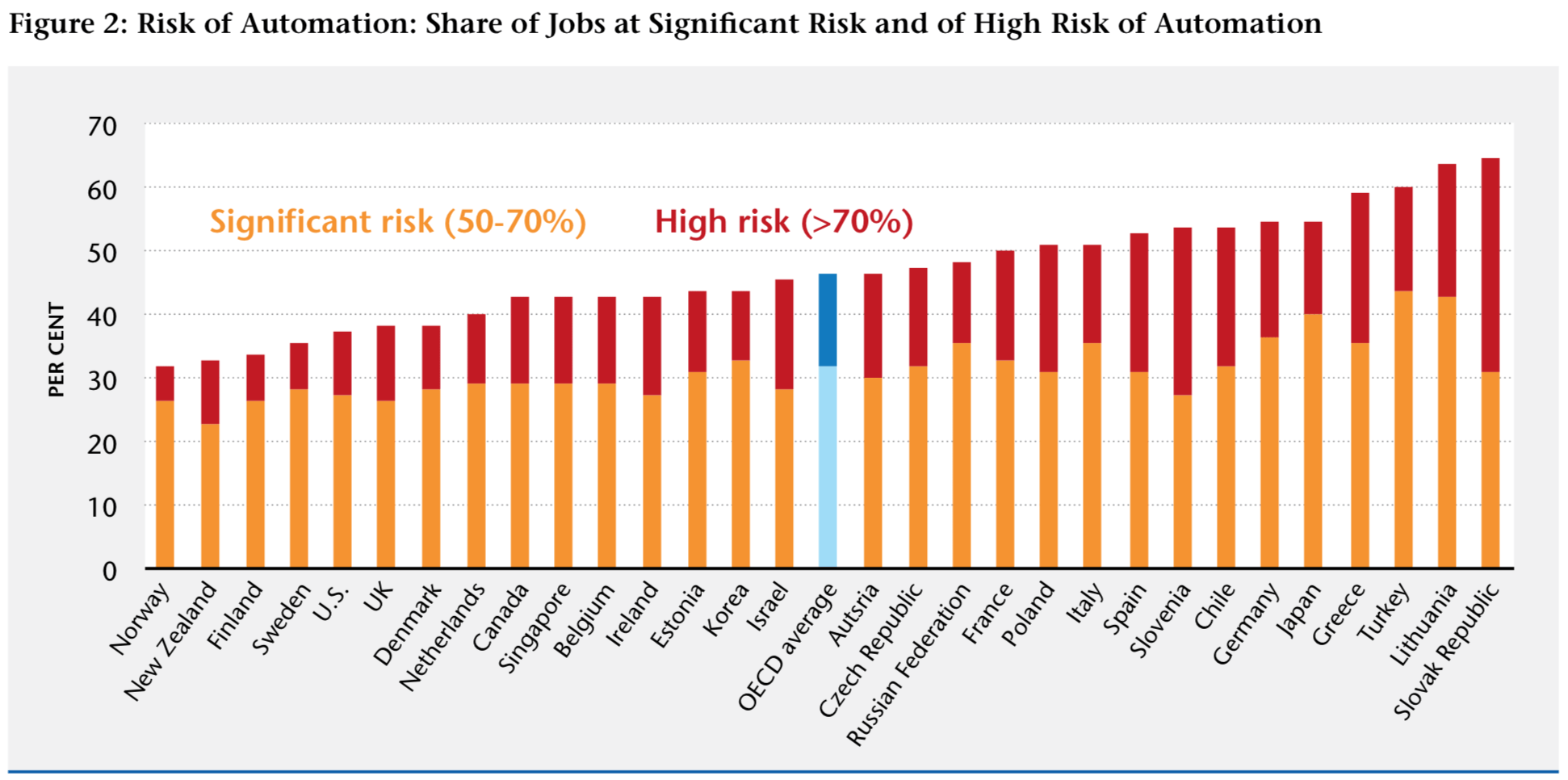

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and McKinsey have calculated the risk of job dislocation as a result of automation (Figure 2) for a variety of countries. The results should not encourage either public or private complacency. The OECD estimates that roughly 15 per cent of Canadian jobs are at high risk of automation and a further 28 per cent are at significant risk. This points to enormous forthcoming churn in Canadian labor markets, where still-unclear new jobs with new skill sets will be created while existing jobs with existing skill sets will be dislocated.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and McKinsey have calculated the risk of job dislocation as a result of automation (Figure 2) for a variety of countries. The results should not encourage either public or private complacency. The OECD estimates that roughly 15 per cent of Canadian jobs are at high risk of automation and a further 28 per cent are at significant risk. This points to enormous forthcoming churn in Canadian labor markets, where still-unclear new jobs with new skill sets will be created while existing jobs with existing skill sets will be dislocated.

Preparing students with the skill sets of the future and re-skilling current workers at scale for those new jobs are just as challenging and important as being at the leading edge of the technology curve to keep Canadian business competitive. Indeed, successful economies and stable societies will be those who do both.

Disruptive technological change is transforming not only the goods and services we consume and the skills needed to produce them, but also business models and the “production function” itself.

Data is now a factor of production alongside labor and capital for info-tech titans, and that capital is increasingly intangible rather than the bricks and mortar of old. To an under-appreciated extent, info-tech companies are intermediaries, like banks—one intermediates money while one intermediates data, and both depend on public confidence to operate.

The info-tech business model of acquiring information about users from users and then monetizing this data through predictive analytic models depends on user trust and data rights, and that is why the Cambridge Analytica scandal is so damaging, not just to Facebook but ultimately to the unregulated info-tech business model.

And that is why trust and values will become such an important part of the technology sector going forward. My perspective is that trust can be a competitive differentiator in the global tech market, just as safety is in the food sector, and Canada should seek to differentiate its tech sector through values—“tech for good”—as well as great home-grown technology and exciting products and services. This would require real effort and likely a flexible mixture of some data safeguards regulation, explicit corporate commitments, an emphasis on values in the training of our tech workforce, and public leadership. But the payoff in terms of building the Canada tech brand and deepening the attractiveness of our tech superclusters to global talent and capital could be transformative.

Contributing Writer Kevin Lynch is Vice Chair, BMO Financial Group and Former Clerk of the Privy Council of Canada.

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave