Ottawa Needs to Focus on Business Investment and Economic Growth

Perrin Beatty

One of the political battlefields in the Canadian budgetary process is the question of how business—big, medium and small—gets treated in the strategic landscape of any government’s fiscal priorities, within and beyond the usual Liberal and Conservative clichés. As President of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, Perrin Beatty processes every budget through that lens. Here’s his invaluable insight into the 2018 budget.

If ever there were any doubt about why the federal government needs to urgently enact policy measures aimed at boosting business investment and economic growth, look no further than its recent budget. Lots and lots of new spending initiatives were announced. However, the fundamental question about how we pay for them was left up in the air. Borrowing more and running higher deficits just punts the problem into the future. And, as the government itself attests, there are significant risks that lie ahead for the Canadian economy. Ottawa missed an important opportunity to set a clear path in its budget towards mitigating those risks. Now, it needs to turn its attention to the growth side of the equation. And it needs to do so quickly.

Budget 2018 was all about spending—new spending initiatives and enhanced spending for programs that aim to: support low-wage Canadians; address gender inequality; support First Nations development; strengthen Indigenous rights and self-determination; promote skills and research; improve health and environmental stewardship; and enhance justice and security. These are all laudable goals. Canadian businesses stand to benefit from measures to support women entrepreneurs, small business growth, skills training, innovation, and cybersecurity. There will also be some important policy improvements made, particularly with respect to the tax treatment of small business and simplification of business support programs.

What is missing, however, is any consideration of the fundamental issues that every business person must take into account every day. Where is the plan to balance the books? How do we manage the risks that lie ahead? How do we grow? For the federal government, how do we ensure a fiscal and regulatory environment that encourages businesses to invest, employ, and grow—in other words, to create the economic wealth required to pay for Ottawa’s ambitious spending plans.

The government is betting heavily on a buoyant economy to fund its spending initiatives and meet its newly adjusted fiscal targets. The government’s fiscal projections are pretty much in line with current trends. As a percentage of GDP, federal spending and tax revenue projections for the next five years look very much like the reality of the past five years. And, based on those assumptions, the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to continue its gradual decline slightly by 2022, even though Ottawa will be ringing up close to $80 billion dollars in additional debt.

The problem is that the economy is unlikely to maintain its current course at near- full capacity. The budget’s rosy economic assumptions will be put to the test by the risks the government itself identifies—growing protectionism and uncertainty over NAFTA negotiations, tightening monetary policies worldwide, and the risk that higher interest rates pose for an already overextended household sector in Canada. Recent U.S. tax reforms are another serious risk to business investment in Canada that is missing from the budget’s calculations—we await further analysis.

It’s time for a reality check. Given the risks that lie ahead, it would be a miracle if the Canadian economy were to meet the expectations set for it over the next five years in terms of either employment or growth. Not only would it defy the business cycle, but it doesn’t make sense in light of the government’s objective of encouraging currently underrepresented groups to join the labour force. Chances are that the deficit will be much higher than expected. The Employment Insurance Account will be the place to watch. With new programs that will be funded from EI, higher than expected unemployment will translate rapidly into a deficit in the account, and eventually into higher payroll taxes for Canadian business.

Higher interest rates are another risk that is underplayed in the budget. The Canadian government’s long bond rate is already near the average level projected for the year ahead and it is moving higher in line with rates in the U.S. With Canadian household debt at record levels, even a slight jump in long-term interest rates—which in turn affect mortgage and other long-term borrowing rates—is likely to have a significant negative impact on consumer spending and the housing market in Canada. The government estimates that a one percentage point increase in the cost of borrowing would lead to a $3 billion increase in the federal deficit over a period of five years, and that does not take into account the impact that higher interest rates would have in slowing down consumer demand and economic growth. The contingency reserve the budget reinstated to guard against economic risk might well be consumed by higher interest charges alone.

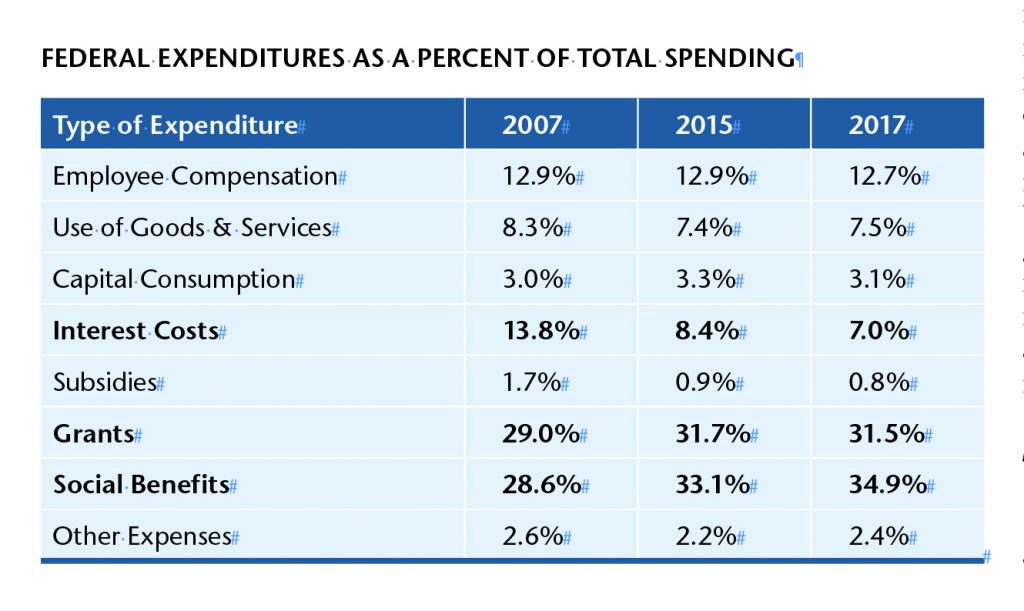

The federal government is ill-prepared to manage a period of rising interest rates or economic weakness. While overall federal spending as a percentage of GDP is approximately the same today as it was 10 years ago, the structure of the government’s expenditures has changed significantly. As interest rates declined, government spending in the form of grants to other levels of government and social benefits increased to fill the void. The leeway to reduce taxes and increase spending provided by an era of low interest rates is now at an end. Today, there is little discretionary room left for the federal government to increase spending in the face of an economic downturn without significantly increasing its fiscal deficit and in turn generating higher interest costs at the expense of real economic stimulus.

Experience has taught us that governments can’t spend their way to prosperity. It’s time to go back to basics—to balance spending with measures that stimulate business investment and economic growth. And that begins by ensuring a competitive tax and regulatory environment for businesses to invest here in Canada.

First step? Focus on reducing barriers to growth. Adopt world class regulatory practices that minimize compliance costs while maximizing the efficacy of regulations. Eliminate regulatory barriers within our own economy and move full force ahead in evening the playing field and achieving greater market access in our international trade agreements. Above all, put in place a tax structure that not only makes Canada competitive with other jurisdictions like the United States that are lowering business tax rates, but which incorporates provisions that enhance investment in productive assets—immediate expensing of capital investments and tax credits for high-risk investments in new technologies and skills training come to mind—and which minimize tax compliance costs.

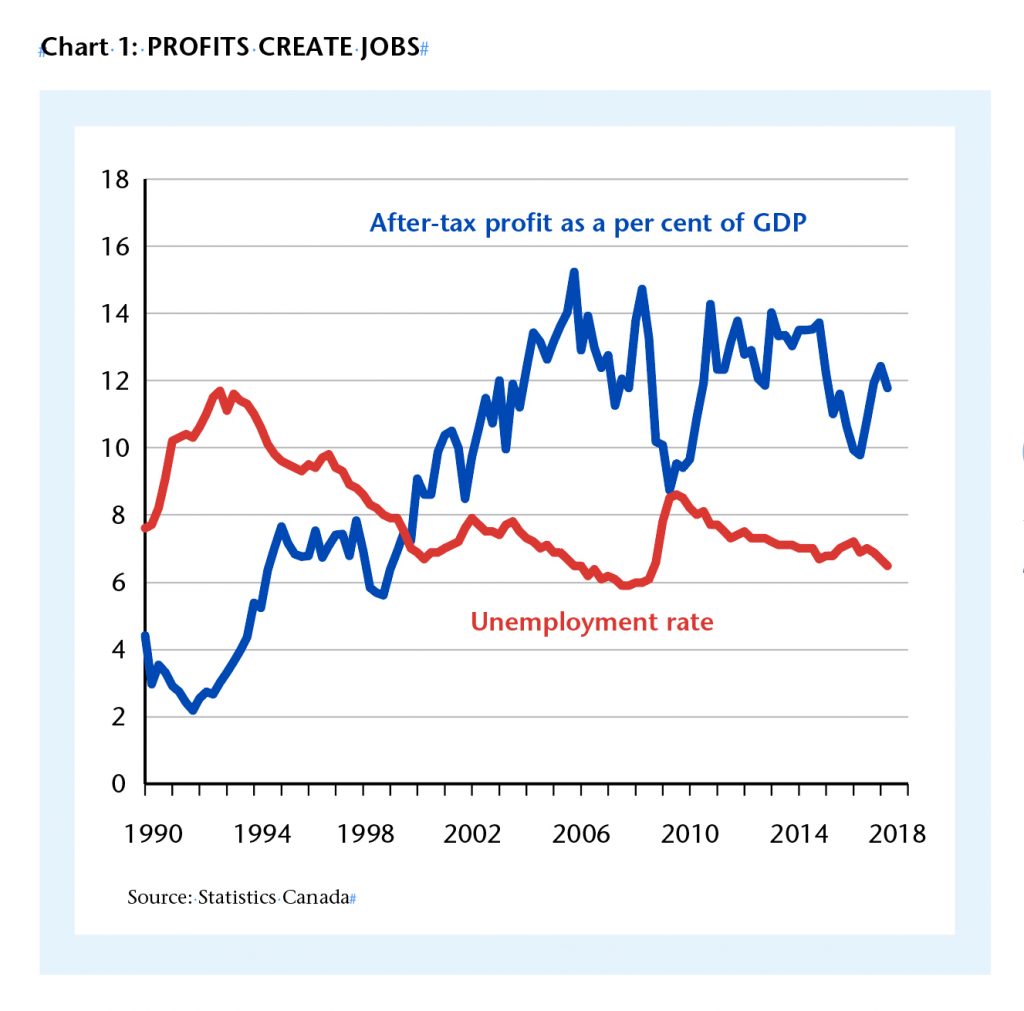

In order to do that, the government needs to engage with business. It needs to recognize that business profits are important to the Canadian economy. They generate jobs. They are the mainstay of prosperity for the middle class—and for all Canadians. When businesses are profitable they grow, create jobs, and invest in the new products, processes, and technologies required to meet customer and stakeholder expectations while remaining competitive.

The record of the past 30 years speaks for itself. The more profitable Canadian companies are, the lower Canada’s rate of unemployment has been. Changes in profitability (measured in terms of after-tax profits as a percent of GDP) are followed immediately by changes in the unemployment rate. Canada’s unemployment rate goes up only when profit margins come under pressure. Unemployment only goes down when profit margins improve.

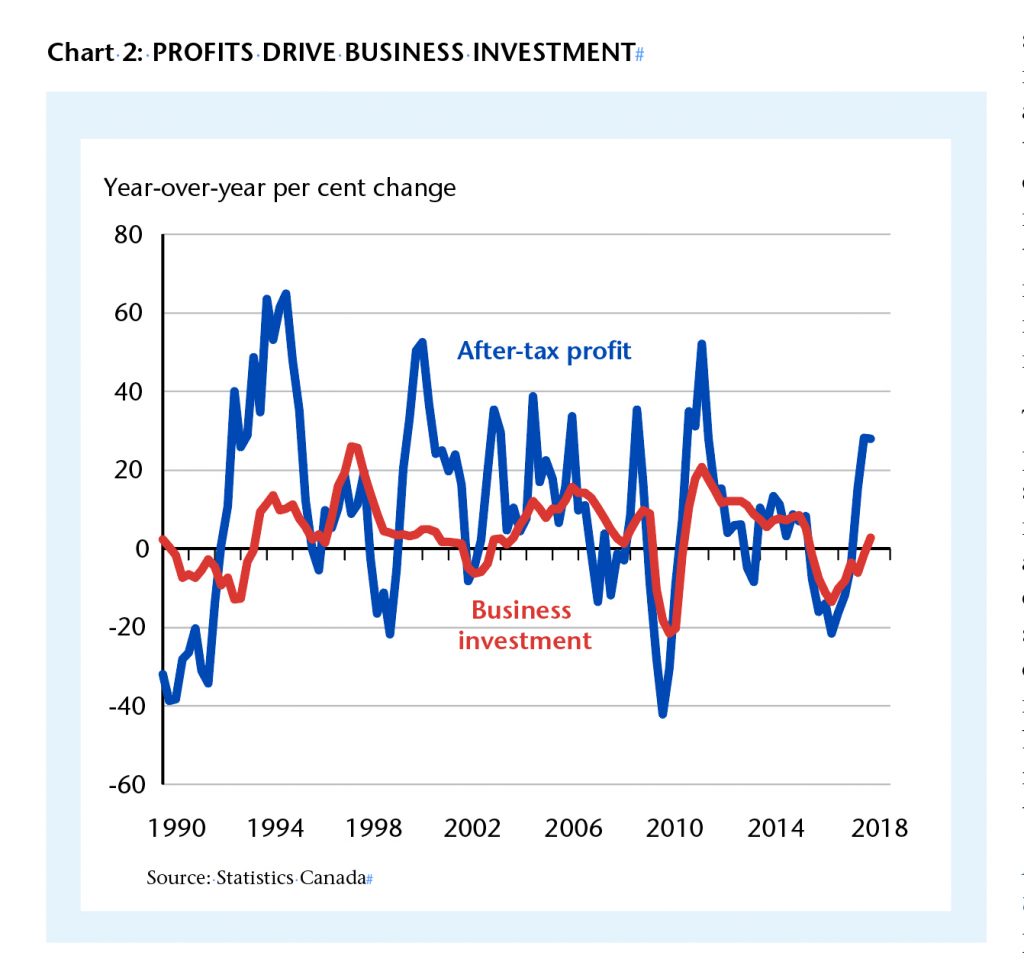

Corporate profits also drive capital investment by Canada’s business sector. Changes in the amount that businesses invest in non-residential structures, machinery, and equipment follow closely on changes in after-tax profits. The most effective thing that governments can do to encourage companies to invest more in innovation, productivity-enhancing technologies, and improved environmental performance is to leave more money in the hands of business to make those investments.

Corporate profits also drive capital investment by Canada’s business sector. Changes in the amount that businesses invest in non-residential structures, machinery, and equipment follow closely on changes in after-tax profits. The most effective thing that governments can do to encourage companies to invest more in innovation, productivity-enhancing technologies, and improved environmental performance is to leave more money in the hands of business to make those investments.

That is why we urgently need a comprehensive review of Canada’s tax system. It’s why we need a thorough reform of our regulatory system. Canada needs a business investment strategy that supports ambitious public sector investments in health care, social programs, inclusiveness, the environment, security—even innovation. Now more than ever, that must be the focus for the federal government over the year ahead.

Perrin Beatty is President and CEO of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

pbeatty@chamber.ca