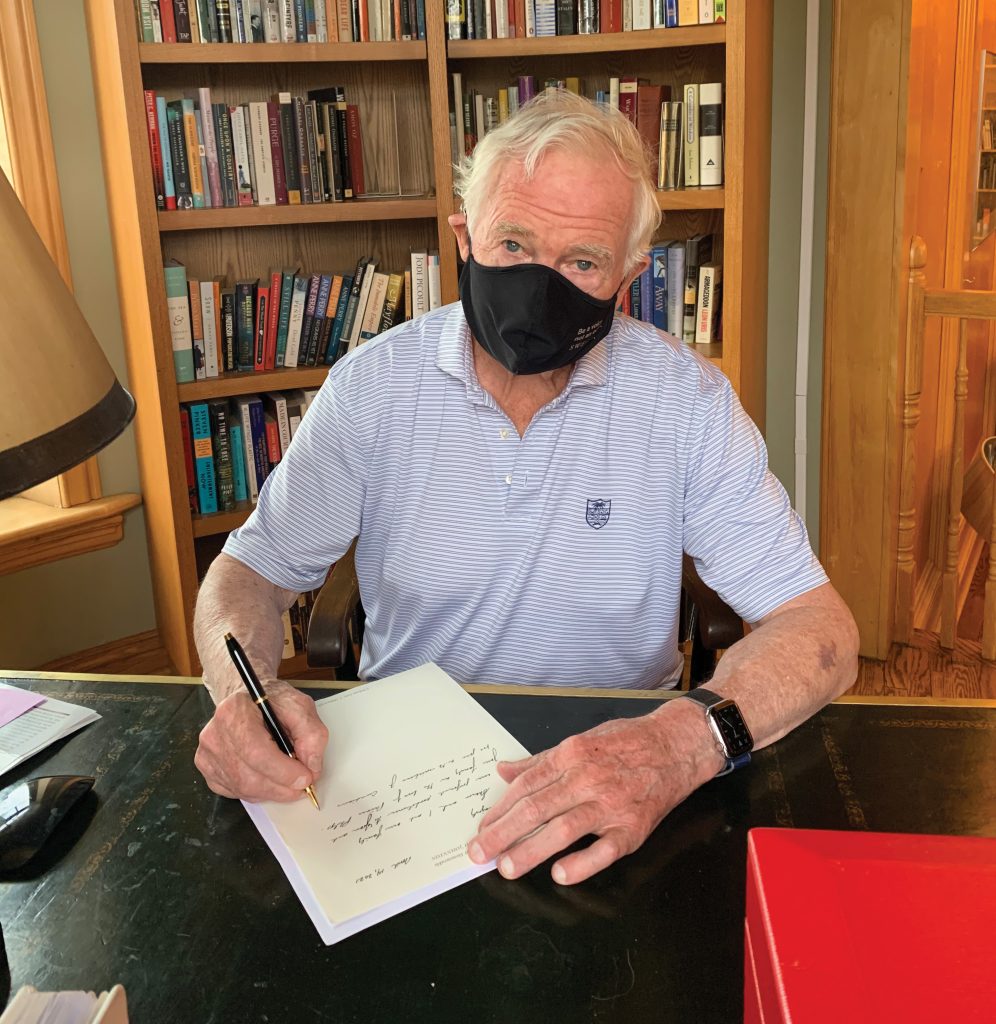

28th Governor General David Johnston: Policy Q & A

Twenty-eighth Governor General David Johnston founded the Rideau Hall Foundation to shine a light on Canadian excellence, and to create the conditions for more Canadians to succeed and to thrive. For this 2021 Policy Magazine-Rideau Hall Foundation Innovation Issue, Policy Editor L. Ian MacDonald spoke with Mr. Johnston by telephone.

Policy: Well, Mr. Johnston, thank you for doing this. We’re in a different context this year, though, aren’t we, so I wanted to start by asking you, How does innovation in a pandemic differ from innovation in normal times? In which case, we have innovation driven by a health emergency and economic crisis, so it’s a different ball game, isn’t it?

David Johnston: Number one, call me David, and number two, we’re really planning a partnership with Policy, and I look forward to this.

Characteristic number one is the emergency and the latest round of measures. Secondly, it’s worldwide. Thirdly, it’s really complex, because of the number of different factors involved. And, number four, it shows our mutual vulnerability, our interdependence on others, in a whole host of ways. It’s a plague, in many ways, that is sent to test us, to determine our strengths and how resilient we are as a society, as an economy, as a body politic. In this case, innovation is driven from a great sense of urgency. But it’s innovation not simply in the scientific endeavour, which, in many respects, has been remarkable—vaccines and therapeutics, which normally take 10 years—but it’s also innovation in resilience and in networks and in interactions in different agencies, governments, and so on. So, this is different than most other challenges to innovation that we have seen and will see.

Policy: What about the coordination and research role of universities in all of this? Almost as the hosts and coordinators of ideas and innovation. As the former head of two of Canada’s world-class universities, McGill and Waterloo, are you seeing some of that experience coming home now?

David Johnston: Well, first of all, I would say that a pandemic tests our talent. Within each nation, and in the different centres of excellence across it, what kind of people have we educated and graduated to take positions in science, in manufacturing and procurement, in government leadership, in coordinating a vast range of activities? How talented are we?

And then, secondly, how much can we draw upon those research and applied technology resources present in those institutions to meet somewhat different circumstances? I think that really indicates a thing that I’ve often emphasized: a smart and caring nation. So key, with each of those adjectives reinforcing the other. The importance of being smart and the importance of being caring and able to respond to this sort of thing completely, with all of the actors, including of course the research and university communities, playing a lead role.

Policy: For example, the medical faculty at McMaster University—in a town that used to be known more for football really than anything else, for the steel mills and the wonderful people of Hamilton—is a world leader. And the whole world is looking to some of the work that McMaster is doing in this crisis.

David Johnston: I’m told, in fact, that there are three areas in Canada where researchers at universities and in combination with the private sector have played substantial roles in the development of the four vaccines that we have approved. And I would point out that our last Nobel Prize winner in medicine, Michael Houghton, comes from the University of Alberta, and in fact won the Nobel Prize for his work on vaccines in earlier epidemics. He came to Canada through the Canada Excellence Research Chair, where we were looking for the best in the world to come and work in these particular areas. He’s just one specific example of how Canada has participated in this remarkable ten-month “Guinness Book of World Records” time of creating new vaccines and establishing a whole talent base around him at the University of Alberta with respect to vaccine research.

Policy: You were mentioning the Nobel Prize. I looked it up, and Canada has won 26 Nobel Prizes. Two of them, Mr. Pearson obviously with the Peace Prize in 1956 and Alice Munro for Literature in 2013. But most of the rest have been university researchers, from Frederick Banting back in 1922 and the discovery of insulin, all the way forward to Michael Houghton in 2020 for his work on Hep-C and Donna Strickland in physics at the University of Waterloo in 2018. She is one of yours.

David Johnston: We’re so proud of Donna Strickland. But, you know, we celebrate the 100th anniversary of insulin next year, which is really remarkable. And Michael Houghton last year. And Art McDonald was physics at Queen’s about four or five years ago based on the mine in Sudbury. I know that well because I grew up in Copper Cliff, beside the largest smokestack in the world, and that mine was very close and that’s where he actually traced those waves coming from the sun that won the Nobel Prize.

Donna Strickland is a very interesting story. It has to do with innovation because Mike Lazaridis, who developed BlackBerry, which began as a co-op at the University of Waterloo, has invested probably about $250 million dollars in physics in and around Waterloo at the Perimeter Institute of Theoretical Physics and the Institute of Quantum Computing at the university. And I said when Mike did that, because of his own drive in exploring physics, that we’d see a Nobel Prize won within the next decade. Well, we did. But it wasn’t in theoretical physics, it was actually in applied physics. Donna’s work involved driving a laser faster, smarter, more powerfully and more accurately. The first application was during live surgery, and it was based on work she did at the University of Rochester.

But, again, recruited from Rochester to Canada in the physics department, and here we are with the Nobel Prize. And I see more of that to come with Canadian innovation, where we are doing basic research well. We need more of the Mike Lazaridises of the world who understand the importance of the theories and then the application that comes from it with the development of a company like BlackBerry.

Policy: In all of this, what are the challenges and opportunities in innovation for Indigenous, Black and culturally diverse Canadians, for gender equity and for the youth whose lives have been disrupted by the pandemic in the last year? We know that the Rideau Hall Foundation has the Catapult initiative that seems like it’s very timely as well as very worthy.

David Johnston: A couple of things. The first would be, as Warren Buffett says, “When the tide goes out, you see who is swimming naked.” One of the things that the pandemic has done is that it has tested us as a nation to see who our most vulnerable people are. And we had some glaring examples of truly terrible tragedies. The number of deaths of senior people, particularly those in institutions, is just horrific. We stand very poorly against other nations around the world in that respect.

Our minority communities, in particular Indigenous people, have been especially hit hard because of this for a whole host of reasons: the health facilities available, living in cramped quarters, having to worry about finances, etc. And there has been a good response, I think, in the case of vaccinations and some of the care in Indigenous communities. But it exposes those challenges in our society, and you judge the health of a society by how it deals with its most vulnerable populations. And we have much to do. On the good side, certainly following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we have seen a strong, collective effort in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians alike to do things better. And certainly, the Rideau Hall Foundation is playing an important role in that. Catapult Canada is a very good example of finding ways of identifying the best paths forward for young people who are in marginalized communities of various kinds and providing them with the financial help and the mentoring and the career paths so they can advance.

A more specific initiative of the Rideau Hall Foundation is our Indigenous Teachers Initiative. RHF will invest new resources into Indigenous education and support innovation to increase program sustainability and number of Indigenous teachers across Canada. We are supporting other partners like Indspire and faculties of education across the country to develop a special stream of students, Indigenous youth, who are identified as early as grade school, who are provided with scholarship help and mentoring through high school. And then they enter into a scholarship and mentoring program for a Bachelor of Education degree and graduate as secondary school teachers or primary school teachers or early childhood educators through the colleges. At the present time, there is a disproportionately low number of Indigenous youth who take a teaching career path. It is also important to note that we recognize the importance of Indigenous-led and driven initiatives.

Policy: And when you look at the numbers of the pandemic for testing positive and having to recover, and the numbers of cases and even deaths, there is no doubt that there is a discrepancy or a gap between Black and culturally diverse Canadians and white Canadians. What is your sense of that?

David Johnston: Well, I think that is quite accurate. One, the social conditions in those minority communities reinforce a trend of this kind. Number two, there is more of a hesitancy, I think, in those communities to trust the protocols that are part of this pandemic and to be able to provide the necessary protection. And, thirdly, there is a little more reluctance with respect to vaccines because of trust factors.

But I think the fundamental point I would make about those communities is the overall point of how important trust is. The nations that have done best in this pandemic, by and large, have had high levels of trust in their public institutions and their leadership. Think of New Zealand. Think of Australia. Think of Taiwan. Think of Singapore. And think of Finland, for example. Norway. These are countries that have high levels of trust. And, in the case of New Zealand and Australia, it was the government saying, “You’ll be hit hard, and you’ll be hit fast, and you’ll get on top of this thing.” Their mortality rate is among the very lowest in the world. And as the pandemic has come into their countries, they hit it right on and their population said, “Yes, we understand what science is telling us and what policy is telling us, and we will make the sacrifices now so that we can get this thing behind us and get on with our lives.”

Nations that have not had that level of trust have had so much more difficulty and the bottom-line result is a very cruel one: the mortality and the percent of the population.

Policy: And what about the issue of gender equity and the extra burdens that have befallen women in all of this, both in terms of employment losses and extra burdens they’ve had to take on at home with the kids out of school?

David Johnston: Again, I think that it indicates that when you have a very unusual enemy like the pandemic sweeping through, it exposes some of our underlying problems. And the reality is that there is a higher concentration of women in the business sectors that have been hardest hit: the restaurant and tourism industries, for example, and women working in factories or in jobs where they cannot work from home. That’s been a factor.

Children not being able to go to school and having to stay at home. The mothers have to cope with that. Very often there are homes that do not have the kind of IT connections that are necessary and very often with no access to them, and very often, also, attempting to maintain some kind of semblance of functioning in a home and looking after the children and holding a job. These are all challenges, and there have been some very positive efforts to provide relief and assistance, but nevertheless, the problem is a large one and it will continue, I think, after this pandemic is over until we establish true gender equity in the world of work.

Policy: And, based on your work, you just referred to the question of public trust and one of your books, published in 2018, is called Trust. What is your sense of Canadians’ trust in the governments at all levels as we come through this pandemic and what elements of that trust will need restoration when we emerge from all this? I don’t know about you, but I have a sense that if there is one thing that people have no tolerance for right now, it’s politics as usual.

David Johnston: Politics, and I think life, will be different following this test that we’ve had. At the Rideau Hall Foundation we have a partnership with Edelman to track this. Edelman has been measuring trust in 30 to 35 OECD countries for 20 years. It was interesting that in their survey in 2018, Canada for the first time fell into the “distruster” nation category.

That would be the bottom half of the measured countries. Meaning that fewer than the majority of the population trusted government, NGOs, media and business. And it was interesting that business was at the bottom of that heap and that NGOs were at the top. In 2019, all of a sudden, business rose to the top. Still, with us being a distrustful nation, but it was at the top of those four. And then as the pandemic hit, all of a sudden, in March/April 2020, business fell to the bottom and government rose to the top. Government has now come down a bit. That, I think, indicates just how trust has varied during the period of the pandemic.

As I indicated earlier, I think the nations that have been those most successful are the ones that have had the greatest trust in their governmental institutions, but also in their NGOs, their media and their private sector. I joke about starting our own Tea Party in Canada, I say to my American friends, that this Tea Party would have three “Ts” to achieve: one would be truth, the second would be transparency, and the third would be trust. So, just as we expect that from our scientists and our public health officers, we also expect that from our political leaders. To tell the truth. To be transparent about it and to constantly recognize the trust comes in on foot and goes out on horseback. That you can destroy it very easily. I think we will have some work to be done when this pandemic ends to rebuild trust.

Policy: I wonder how you think, in all of your travels and talking to people and your notetaking, how you see the nature of work changing because of the pandemic. We now live in the Zoom age and whoever heard of that two years ago?

David Johnston: It will clearly change, there is no question about that. The digital revolution is advancing at a pace that we have not seen in human history. It took 300 years for the printing press to reach the majority of the population of Western Europe and, in so doing, managed to take that backwards civilization (kind of the Dark Ages of Europe in pre-15th/16th century where Islam, India and China were well ahead of civilizations). But it was 300 years for that revolution in communication to take place. If you look at the internet, which really burst into awareness in 1993, it took 10 years for it to reach the majority of the world’s population. And that digital revolution has been accelerating even more than that, but we have had the huge acceleration in the technology but not nearly so much an acceleration in the human capacity to adapt and use

the tools.

So, adaptation, innovation and resilience will be very key to how we deal with that and how we use this digital revolution and other changes to our way of doing things to advance the human condition. And, you know, just the notion of working from home as part of the Industrial Revolution when people did their work at home and took it often to be sold or to work on the farms, we have come back to that in a way and will have to adjust to that. Clearly, the notion of investing in knowledge and skills will become even more paramount. We must educate our children and our workforce to be able to understand new technology, new phenomena, and the ability to learn how to learn and to be very resilient.

And, as a nation, I think sovereignty will be defined in how well we develop talent and knowledge and how well we ensure that it is available to everyone, and how well we put it to use. That will be the defining factor of the 21st century. That’s, I think, where Canada has an opportunity to have a real edge.

Policy: Finally, in terms of summing up, the difference of innovation in peacetime, if I can put it that way, and the equivalent wartime conditions of a national and global emergency, it is a different kind of research, isn’t it? And there is a quality of urgency that is not normally apparent.

David Johnston: Let’s not have to have a war to become innovative. But to follow the lessons from the war, which is to respond with a sense of urgency that required us to focus on what was necessary and do it with unparalleled effort and tenacity. And have the seamless cooperation of business and government and people all across the country supporting that kind of effort. I don’t want us to have to have that kind of sense of urgency to have to steel the nation into working better.

We really should worry about complacency in this beautiful country of Canada, where life has been really pretty comfortable for us. No wars for 200 years. We have a wonderful geography. Vast, large and natural resources to be developed, etc. Stable government. All of those things. We shouldn’t have to find ourselves in the circumstances of some of the countries that are really beset by enemies from all sides to be able to work with zeal and to improve our situation and to be innovators. And to share our knowledge with the world.

I really believe that Canada should aspire to be a place where talent has equality of opportunity. Where we believe that everybody should have the best learning opportunities available. To give them a new understanding of the human brain, the human mind. To enhance our advantages and learn better. And then use that knowledge to spread around the world and see ourselves as the prime movers in improving the human condition.