2021 Fiscal Update: The Moneyball Version

Kevin Page

December 15, 2021

Economic and fiscal updates and budgets are multi-dimensional documents. They are a combination of policy, numbers, and politics. The Economic and Fiscal Update for 2021 presented to Parliament by Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland ticked off all those boxes, within the exceptional context of a persistent pandemic that asserted its influence by transplanting the statement itself from the House of Commons to a screen near you 90 minutes before show time.

In the interest of focus and expediency, it is possible to look at the Update through the lens of numbers. What stories do the numbers tell? This could be termed the Moneyball version, after the bestselling book (and subsequent Brad Pitt movie) Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis.

The 2021 Update was a traditional mid-year review with a focus on the economic and financial condition of the country. Of course, in the context of the record fiscal supports and budgetary deficits expended and incurred to fight the economic influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s hard to convey a traditional approach.

The post-crisis transition return to a more traditional mid-year review is garnering mixed reviews. Some reviews are positive. Some want to see the end of eye- popping spending and deficits. Some reviews are negative, concerned that the government has missed opportunities to address problems — more supports; less inflation; more fiscal guidelines. You get the picture.

Updates provide an economic outlook for planning purposes. The average private sector forecast assumes a relatively strong recovery going forward with gradual improvements in lowering inflation, stronger labour markets and incremental increases in interest rates. Exchange rates and oil prices are flatlined. The “real” economy is weaker over the short term with respect to Budget 2021. However, nominal GDP is notably higher because of higher GDP inflation in the short term (which is not unwound). Two alternative scenarios are provided (i.e., stronger/weaker growth over short term).

Given COVID-related uncertainty, it is a good Moneyball bet that this is a relatively optimistic and hopeful planning outlook. On the other (economist) hand, given the methodology (i.e., the government’s average private-sector forecast approach), it is not unreasonable or biased. At the end of the day, we need something to base plans and polices on, even within the contingencies of a pandemic.

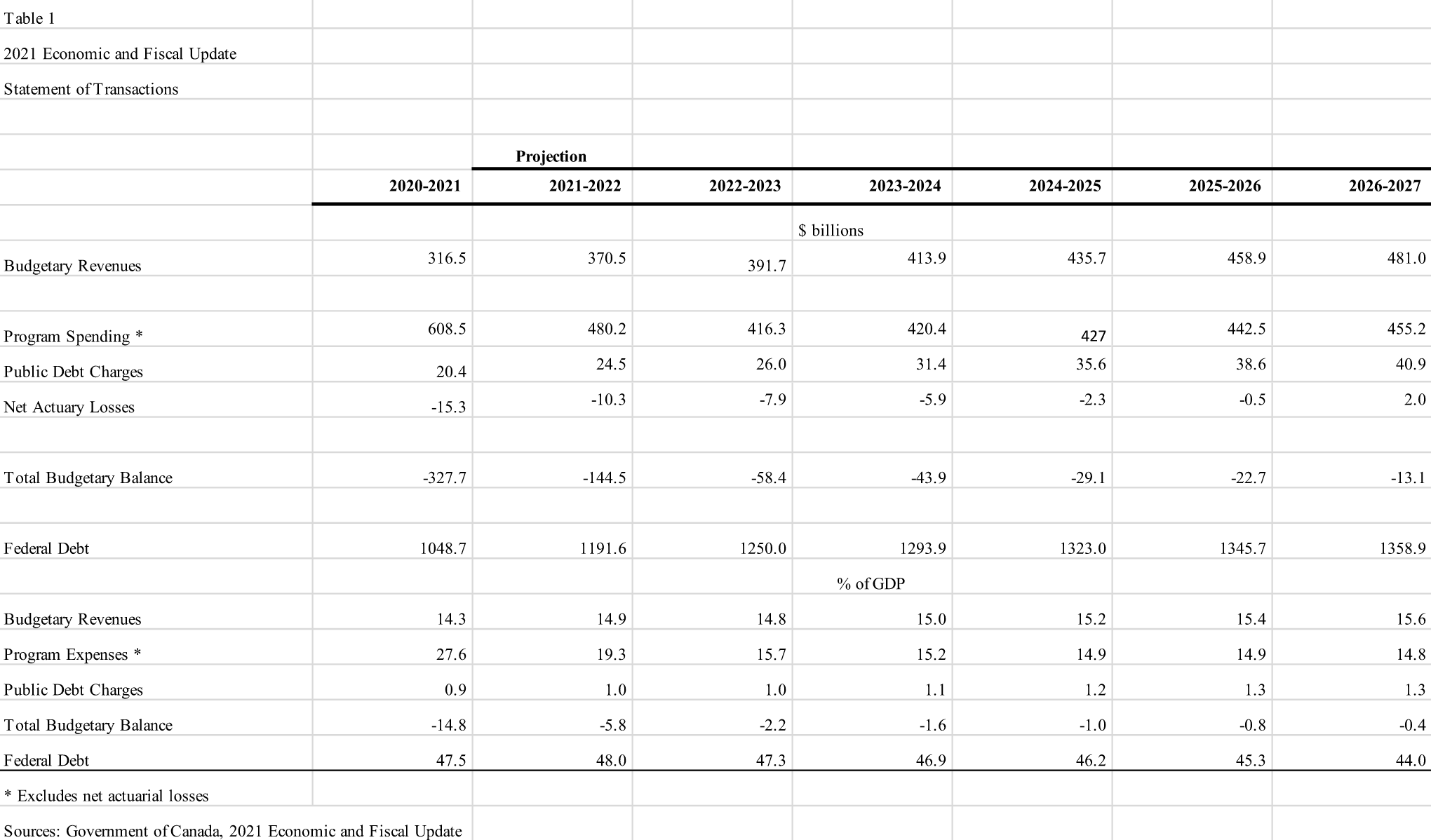

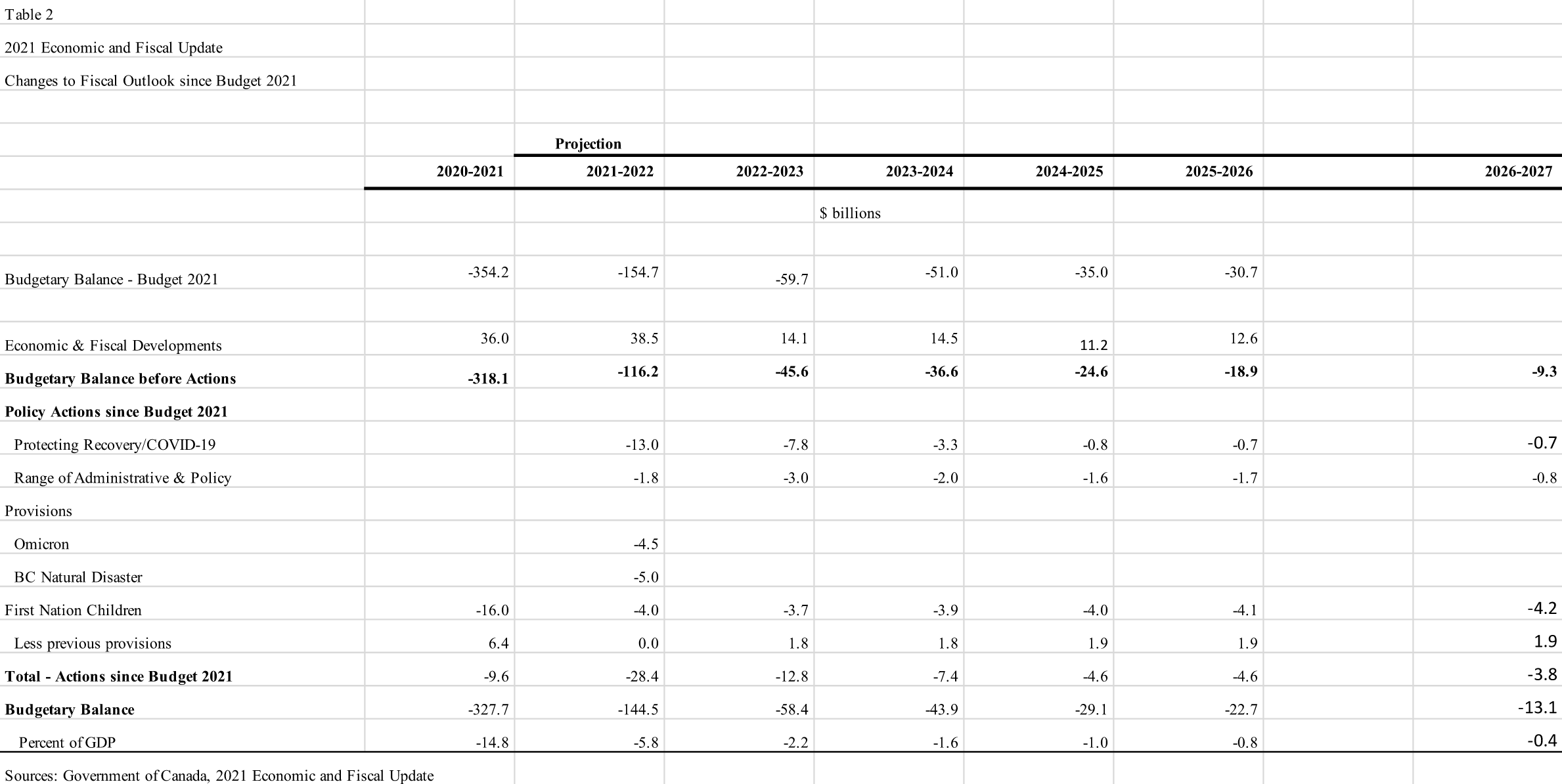

Regarding the fiscal outlook, in updates and/or budgets there are really only two tables that matter most – the statement of transactions (Table 1 below) and the changes since the previous budget (Table 2 below). Moneyball people go straight to the numbers.

The tables tell us that baseline spending and revenue numbers are much improved since Budget 2021. Other tables help us understand that this is largely because of higher nominal GDP (inflation-based) — which boosts the tax intake — and lower spending (some planned Covid spending did not get out the door over the past two years).

Cumulative baseline budgetary deficits are down about $125 billion over medium-term (a six-year horizon). Projected deficits drop dramatically in nominal terms and as a percent of GDP over the next few years as historic spending supports are unwound. The debt-to-GDP ratio remains elevated but trends down over the medium-term planning framework.

Cumulative baseline budgetary deficits are down about $125 billion over medium-term (a six-year horizon). Projected deficits drop dramatically in nominal terms and as a percent of GDP over the next few years as historic spending supports are unwound. The debt-to-GDP ratio remains elevated but trends down over the medium-term planning framework.

Relative to Budget 2021, there is about $70 billion in new spending over the medium-term planning framework, much of which is front-end loaded. There is about $30 billion dedicated to COVID (health and recovery) supports; $24 billion (net) for First Nations children ($40 billion in total); $5 billion for British Columbia flood relief; and $11 billion for a range of government operations and policy.

From the Moneyball perspective, the $70 billion in new spending eats into some of the fiscal dividend provided by the improved outlook (Table 2) but leaves some space left over to fund election 2021 platform initiatives. The Liberals had a number of early spending initiatives in the platform that were not incorporated into the planning outlook including higher Canada Health Transfers.

The big policy announcement was $40 billion for First Nations. This is related in part to an ongoing Canada Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) case. Government efforts to “book” the liability in 2020-21 delayed the release of the public accounts and the update. The forward-looking increases in spending are set aside to improve well being for First Nations children. We need new policies and programs led by First Nations people.

There were no new commitments regarding fiscal targets or rules. No commitments to spending reviews. An opportunity missed.

There was some hint (buried in a textbox) that the government will present something that looks like a growth agenda in the winter 2022 budget.

While a number of factors could impact the timing of the 2022 budget (e.g., more COVID developments), this more traditional approach to a mid-year review could imply an earlier budget timing to incorporate 2021 platform initiatives.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa. He was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.