1980 referendum: Trudeau’s ‘Elliott’ speech a turning point in Canadian history

Forty years ago, on May 20th, 1980, Quebecers voted ‘No’ in the referendum. Our Editor looks back on Pierre Trudeau’s famous “Elliott” speech.

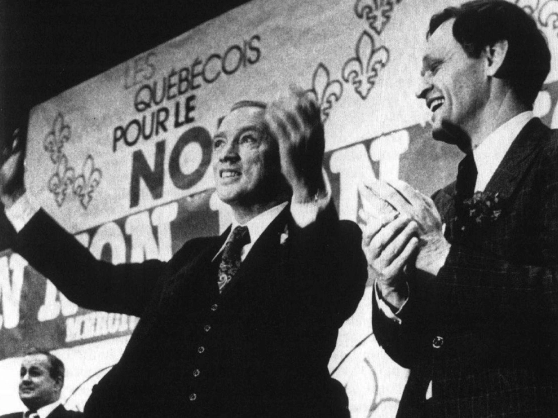

Tedd Church/Montreal Gazette files

L. Ian MacDonald/For the Montreal Gazette

May 14, 2020

It was the defining moment of the first Quebec referendum, and one of the greatest political speeches in modern Canadian history.

But the Elliott speech, as it has been known since Pierre Trudeau delivered it on May 14, 1980, was almost an accident of history.

It began two days earlier with two short paragraphs in a story included in daily morning clippings for a meeting of senior staff and advisers with the prime minister.In the piece, René Lévesque was quoted as saying Trudeau was not a real French-Canadian because his mother’s name was Elliott. It had been included in the daily news digest by Claude Morin of the PM’s referendum staff group.

“Some of the people didn’t think it was important,” Morin would later recall. “But it was clear he wanted to discuss it.”

Trudeau speech writer André Burelle began writing up a list of “Péquistes with English names,” including many of Lévesque’s closest advisers and cabinet ministers.

Now, everyone around the table saw where Trudeau was going with it. Burelle didn’t write a text for the prime minister, just a list of names he committed to memory.Two nights later at the Paul Sauvé Arena, Trudeau delivered the coup de grâce of the campaign.

“Bien sûr que mon nom est Pierre Elliott Trudeau,” he declared. “C’était le nom de ma mère, voyez-vous?”

He continued: “It was the name borne by the Elliotts who came to Canada more than 200 years ago. It is the name of the Elliotts who, more than 100 years ago, settled in St-Gabriel-de-Brandon, where you can still see their names in the cemetery.”

He was just getting started. “Mon nom est Québécois,” he said in a play on the words of the No campaign slogan, “Mon non est Québécois.”“But my name is a Canadian name also, and that’s the story of my name.”

He was not yet done. He recited the names of Pierre Marc Johnson and his father and brother Daniel, a past premier and two future ones. “Now I ask you, is Johnson an English name or a French name?” Trudeau threw in the names of prominent Péquistes such as Louis O’Neill and Robert Burns, members of an Irish-Québécois demographic that had so integrated with vieille-souche francophone families over generations that many of the province’s O’Learys and Doyles didn’t speak a word of English.

The crowd had been chanting “Trudeau, Trudeau,” but switched to cries of “Elliott, Elliott.”This wasn’t about “le bargaining power” or about a mandate question to negotiate sovereignty-association — it was about a sense of identity, Québécois et Canadien, and being both. And there was also a question of pride in Trudeau as both a native son of Quebec and one who represented Quebecers on the Canadian and world stage.

It was the moment the federalist forces clinched the vote that was delivered six days later on May 20, winning the referendum by a convincing 60-40 margin.

It was the heart of a speech that almost didn’t happen, in a campaign that almost didn’t have Trudeau as a player in it.

Only a year earlier, Trudeau had been defeated in the May 22, 1979 election by Conservative Leader Joe Clark. But Clark, seemingly unmindful that he led a minority government, brought in a fall budget that included an 18-cent-a-gallon gasoline tax. Amid the blowback, Clark was urged by his advisers to call off the budget vote.Clark had until the afternoon of the Dec. 13 vote to give notice of cancellation, and could have had the House adjourn for the holidays instead. Or Clark could easily have bought off the Créditistes of Fabien Roy and their six rural Quebec MPs by giving them office space and staff normally reserved for recognized parties in the Commons. But the Créditistes abstained while three Conservative members were absent. The Conservatives famously lost the budget and government by a vote of 139-133.

Trudeau, who had previously announced his retirement, allowed himself to be talked out of it. Going into the campaign with the Liberals 20 points ahead, Trudeau confided to one old friend that he would win the election, fight the referendum, stay on for two or three years as prime minister and then “do what I want to do” for the rest of his life.He did all four. But without that fateful Tory budget vote in the House, there would have been no role for Trudeau in the referendum and down the road, no Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Elliott speech was the capstone of four carefully planned Trudeau interventions in the referendum campaign.

There had already been an important event starring supporting players, the all-women’s Yvette rally at the Montreal Forum on April 7, which had moved undecided and discreet public opinion to the No side. The Yvettes were spontaneously organized by suburban Montreal women such as Louise Robic, later Quebec Liberal Party president and a cabinet minister in the government of Robert Bourassa. The women insisted on reserving the 15,000-seat home of the Canadiens over the objections of Liberal organizers, who feared the place would be half-empty.They had been provoked by PQ cabinet member Lise Payette. She committed the first major blunder of the Yes campaign when she compared women No voters to Yvettes, the name of a submissive character in a school reader. Even worse, she said Liberal Leader Claude Ryan had married an Yvette. The Yvettes’ star lineup featured Madeleine Ryan, Liberal MNA Solange Chaput-Rolland, federal Health Minister Monique Bégin, incoming House of Commons Speaker Jeanne Sauvé and women’s rights pioneer Thérèse Casgrain, who four decades earlier had worked to win women the right to vote in Quebec.

Fifteen thousand women paid $5 at the door and filled the Forum to overflowing, inspiring rallies of like-minded women around the province.As for Trudeau, he formally entered the referendum fray on April 15 with a House speech remarkable for its rhetorical flourish. “What is the feeling of belonging to a country, which we call citizenship?” he asked. “And what is the feeling of loving a country, which we call patriotism?”

Lévesque’s mandate question for sovereignty-association, Trudeau said, did not meet the test of country. At 114 words in French, 107 words in English, it was a soft question that promised a second referendum to ratify a sovereign Quebec in economic association with Canada. Trudeau pointed out that Lévesque “must first recognize that, to associate, one must associate with someone.” As for sovereignty, Lévesque had no such mandate. Trudeau also made the point that with 74 Liberals out of 75 Quebec seats in the House, “we have therefore just received from the people in Quebec a mandate to exercise sovereignty for the entire country.”

Then at a Montreal Chamber of Commerce lunch on May 2, Trudeau put the cat among Lévesque’s pigeons: “What will you do if Quebec votes no?” he asked. “We are entitled to know.” Lévesque’s lame answer, several hours later: “We will continue to go around in circles.”In Quebec City on May 7, Trudeau played the card of favourite son and statesman. He said he wouldn’t be going to Yugoslavia to attend the funeral of Marshal Tito, but flying to Quebec City instead, “not because I felt you needed a hand, but because I myself need to be among family.” And the crowd went wild.

In that referendum period, we saw two leaders who deeply opposed one another on a fundamental question of country, but who also respected one another as a matter of the principled rule of democracy. “It’s not easy,” Lévesque told Yes supporters as he acknowledged defeat on the night of May 20. There was not a single act of violence, as his disappointed followers went home with broken dreams. Nor was there any gloating on the winning side. There was on one side a sense of relief, and on the other a sense of acceptance and, among true believers, a vow of “À la prochaine.”

That says a lot about both Trudeau and Lévesque as sentries of democracy. It was a great privilege for those of us who were there as journalists to cover them both. And they made it easier for all Quebecers, irrespective of language or referendum choice, to be proud of them both. In that unexpected sense, the first referendum was a unifying experience. As he left the Paul Sauvé for his return to Ottawa, Trudeau asked if anyone was going with him. No one was. Some of his advisers were going downtown for dinner with journalists at the Auberge St-Tropez on Crescent St.

The usual spin ensued about the headline of the speech. Trudeau’s press secretary, Patrick Gossage, thought it was his promise of constitutional reform.

“That might be the headline,” I said from across the table. “But it’s not the history. He made history with ‘Elliott’ tonight.” Did he ever. Forty years ago.

L. Ian MacDonald is the Editor of Policy Magazine.