The Geopolitical Economy: Nationalism, Populism and a New ‘Yes, We Can’

Pexels

Pexels

By Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

June 17, 2024

The reality today is an uncomfortable mix of geopolitical turmoil, rising nationalism and rampant populism. A useful lens to try and make sense of it is “economic nationalism” – an old problem, recently re-framed on both the left and the right for a 21st-century economic reality.

While the economy has influenced political trajectories and electoral outcomes since long before James Carville’s “It’s the economy, stupid” was scrawled into conventional wisdom, economic considerations have become complicated by political polarization, by disinformation and by the borderless context of disruption evidenced most recently via the effects of the pandemic lockdown on supply chains and inflation.

The rhetoric of economic nationalism is a narrative of failure – by political leadership, by elites, and by institutions. The failure is rather generic – failing to prevent a loss of economic power or social status by groups within a country, or, by the country itself relative to perceived peers. And the failure narrative itself is couched in identity terms – “us vs. them” – and the attempts to stifle the popular will (populism) by the “them”.

The toolkit of economic nationalism is equally insidious – protectionism, exclusionary industrial policy, anti-immigration rhetoric and measures, rejection of the constraints imposed by economic orthodoxy, hostility to globalization, and antipathy to rules-based international institutions. Plus, economic nationalism is decidedly not a team sport – it sees the world in zero-sum terms, with policies that are designed to increase domestic competitiveness at the expense of other countries – some intended, some unintended.

A modern-day example of economic nationalism is Trumpism. It draws on the angst of many lower middle-class Americans who feel they lost their jobs and economic security to unfair foreign competition and a surge of immigrants, many illegal, competing unfairly with them for unskilled or semi-skilled jobs. To this sense of domestic “hollowing out”, and its perceived failure of “the establishment” to respond, you can add widespread concerns that America’s place in the world is being threatened by a rising foreign economic and military power, China, while others, including allies such as Canada and the EU, are viewed as “taking advantage” of the United States.

Economic nationalism with Chinese characteristics is also on full display in China. Aggressive nationalism has been a hallmark of President Xi Jinping’s leadership. Under President Xi, China has ramped up sabre rattling over Taiwan, anti-western populism, expansive industrial policies under the “Made in China 2025” umbrella, the flouting of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on subsidies, widespread non-tariff protectionist policies, and Party intervention in many sectors of the economy, particularly high tech and digital. Its embrace of a “no limits” partnership with Russia is more geopolitical than neighbourly, with a clear Chinese intent to weaken Western influence and solidarity.

Nor are the forces of economic nationalism limited to the two superpowers – they are also present in the Global South, where “resource nationalism” is on the rise. This is often combined with a “transactional internationalism”, which has been very evident in the response of many developing countries, particularly India, to the West’s sanctions on Russia.

Inaction is seldom the best course when change is inevitable. The question, then, is what course corrections and strategic choices should we contemplate?

On top of this geopolitical turmoil and economic nationalism, but not totally unrelated, is a global economy heading for “The Tepid Twenties” according to the alarming message of the IMF in its April 2024 World Economic Outlook. Global growth will trend downward unless and until there are significant policy course corrections, and foremost among these is to revive productivity, followed by reining in government deficits and debt, finishing the fight against inflation, and constraining the viral outbreak of costly industrial policies.

Canada is clearly in the IMF’s critical sights. We have a serious growth problem – growth in GDP has been mediocre at best for almost a decade, while growth in GDP per capita – the broad measure of living standards – was negative last year and will likely be again this year. More troubling, it is projected to be the weakest of all Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries over the next decade and beyond. Hardly a stirring outlook.

Our problems echo the IMF policy concerns. Our productivity is anemic, with labour productivity falling in 12 of the last 15 quarters. Our competitiveness is poor, with weak innovation and low corporate investment (per dollar of revenue and per worker).

To this list, Canada can also add a post-pandemic addiction to debt by governments, incomprehensible internal trade barriers (costing 5% of GDP per capita) and a regulatory burden that makes it near- impossible to build major infrastructure. Hardly an attractive environment for capital investment, foreign or domestic.

To give a sense of how bad our productivity problem is, consider business-sector average productivity growth in Canada and the United States since 2000: US productivity growth averaged 1.85% per year while Canada was less than half of that, at roughly 0.85% per year. Put differently, by 2023, Canadian business productivity levels were only 70% of the US, the worst relative performance since 1947. And our relative performance is worsening.

Adding to this growth challenge, particularly for a trading nation like Canada, Canadian businesses face a very difficult external environment. De-globalization is a reality, with trade fragmentation spreading, increasing input costs for Canadian business and reducing market opportunities. Canada’s vaunted Indo-Pacific strategy is in tatters – bilateral relations with both China and India are frazzled and we have been excluded from new America-led Asia security pacts.

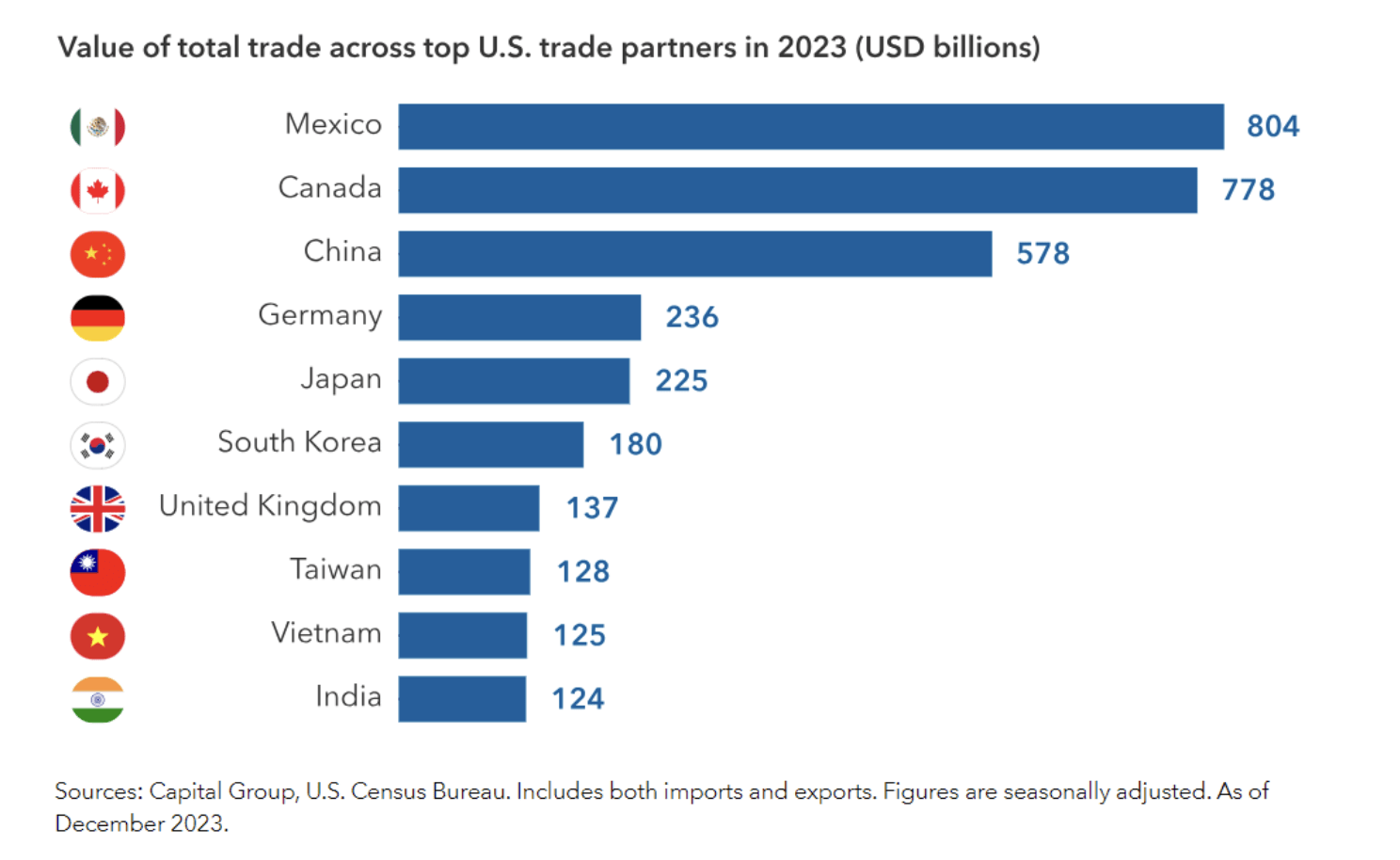

Global supply chains are in flux, but Mexico and the US are attracting the lion’s share of the near-shoring, not Canada. The Brookings Institution has noted that the Biden administration’s nearshoring strategies have positioned Mexico as “the U.S.’ number one trading partner and a crucial investment hub within North America.” Most concerning is the fact that the cornerstone of our trade regime, the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), a.k.a the “new NAFTA”, is up for review in 2026 and the Biden administration is sounding tough while a Trump 2.0 regime, which is looking increasingly likely, is threatening 10% across-the-board tariffs. And the heads-of-government G20, which Canada helped launch in response to the 2008 global financial crisis after years of preparation under Paul Martin’s early leadership as finance minister and prime minister, is now incapable of consensus and, hence, coordinated action.

On top of all this, there is the collective question of how, as a country, do we deal effectively with climate change, with the wars in Ukraine and Gaza and the Russian threat to NATO countries, and with the technological revolution that is AI.

There is little doubt that this is one of the most fraught periods in at least half a century, and history teaches us that successfully managing pivotal moments such as this requires strong leadership, strategic vision, and a willingness to make tough choices.

Inaction is seldom the best course when change is inevitable. The question, then, is what course corrections and strategic choices should we contemplate?

First, we can create leverage with allies. We can do this by increasing our defence spending to the 2% NATO target. We can ship LNG to Europe to help undermine Russia’s insidious energy blackmail. We can fast-track mining of critical minerals. And we can focus on Arctic security and sovereignty.

Second, we can build shields and seize opportunities. We can rebuild fiscal credibility with global financial markets and restore fiscal buffers for the inevitable future shocks. We can double down on improving productivity with a laser focus on easing the regulatory burden, removing internal trade barriers, and stimulating weak corporate investment. We can diversify trade linkages with more focus on southeast Asia and the Americas – a Free Trade Area of the Americas is in our economic and security interests. We can restore the primacy of the points-based, talent-seeking immigration system and be a magnet for skilled, entrepreneurial talent which is unnerved by recent global developments/risks.

Third, we can avoid complacency and parochialism. We can all do this by realizing that the status quo is a choice, not a default, and a risky one in times of great change, which Fareed Zakaria describes so vividly in his new book Age of Revolutions. Corporate Canada needs to take the dual threats of geopolitical turmoil and economic nationalism more seriously.

If we didn’t hit you over the head with it enough, the key phrase in the three points we just made is “Yes, we can”.

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard once observed: “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” We are in one of those periods of change where past relationships are not necessarily sound guides to the future for business – politically, geopolitically, technologically and socially.

We must prepare for this new world. The most competitive firms and the most competitive countries will have the best chance of responding to this uncertainly and these threats. We just need the will to up our competitiveness game.

Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group.

Paul Deegan is CEO of Deegan Public Strategies and was a public affairs executive at BMO and CN.