Friend-Shoring Canada’s Foreign Policy?

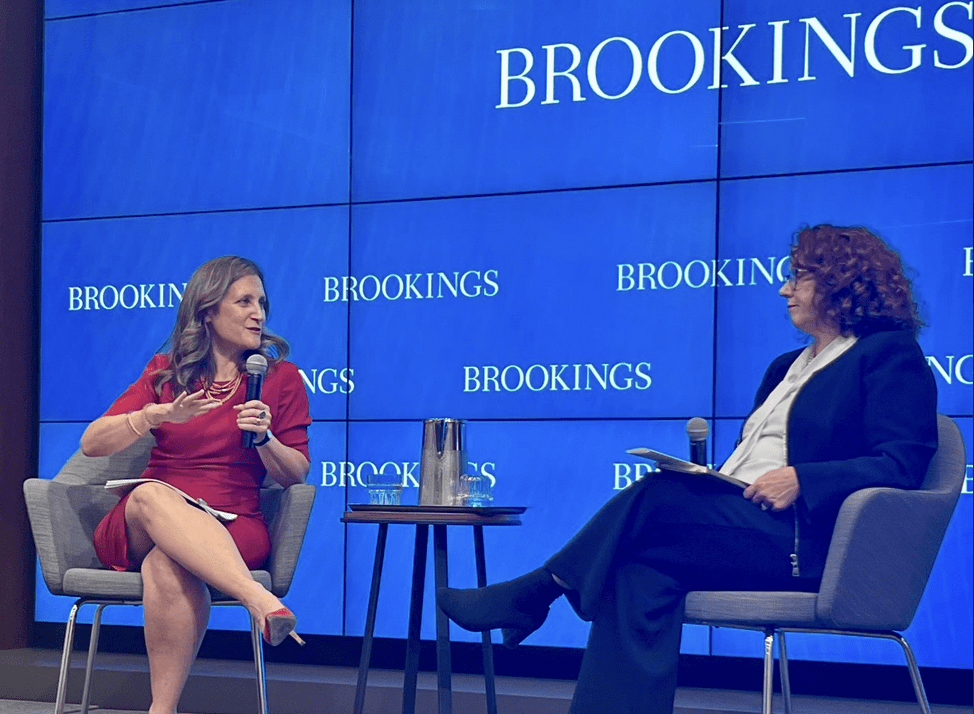

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland with Brookings VP Suzanne Maloney/Twitter

Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland with Brookings VP Suzanne Maloney/Twitter

Kerry Buck and Michael W. Manulak

October 29th, 2022

On October 11th, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland delivered a high-profile speech at the Brookings Institution in Washington on the future of Canada’s trade and economic policy as an extension of our international relations, notably with the wider democratic world.

For Freeland, Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has shown the need for a trade policy reorientation toward what US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has called “friend-shoring.” Freeland’s twist on Yellen’s proposal has implications beyond securing supply chains. Her vision would result in a considerable deepening of social and political ties among democracies. The crux of the approach is that trade with autocracies should be limited and “in-between” states should be incentivized to embrace the values of this new club of democracies. Her proposal is being called, not by the minister herself, “the Freeland doctrine.”

This approach has clear appeal. The world has become a more dangerous and inequitable place. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, nuclear sabre-rattling, and war crimes are only the most blatant challenges to the rules-based international order. China has thrown its economic weight around internationally, with President Xi Jinping recently consolidating domestic power to remove all internal checks and balances. Broader backsliding on democracy underlines the perils of the current international environment.

The impulse to close ranks behind democratic lines, tightening bonds with governments that share our values, is understandable in this context. Yet, there are risks in such an approach.

With the world headed, perhaps inevitably, toward increasing strategic competition, Freeland’s vision could be easily interpreted in a manner that risks exacerbating polarization, undercutting multilateral organizations and international rules. It may be that the most promising approach is to interpret the “Freeland doctrine” to include multi-layered channels of engagement, both with autocracies and in-between countries. Such an approach would capitalize on shared interests and invest in international architecture.

Geopolitical rivalry has grown between the democratic West and autocratic regimes, especially in Beijing and Moscow. A “Thucydides Trap” — coined by Harvard’s Graham Allison to describe the dynamic whereby existing and challenging great powers wage war — may lie on the road ahead, potentially ensnaring states in a conflict spiral. Talk of a new Cold War has become more common and more casual. Implicit in this is the mistaken belief that the world somehow knows how to do Cold Wars and that geopolitical tensions can be safely managed. This view is dangerous and takes us in a direction that is not in the interest of Canada or of democratic societies.

While tensions are increasing, we are not yet in a Cold War. Links between China and democratic countries are far more pervasive than they were with the Soviet Union in the 1940s. Interdependent problems, such as climate change and pandemics, generate shared interests that are of an entirely different scale than experienced by the original cold warriors.

Although the intent of Freeland’s speech is not to make the case for a new Cold War, a deepening of ties among democratic countries and a severing of links with autocratic ones risks doing just that by widening this divide. When our success is an existential threat to autocracies, as Freeland maintains, it is hard to envision positive-sum collaboration flourishing. But by limiting political ties with the world’s autocracies, democracies risk overlooking opportunities to influence the behaviour of autocratic states through engagement. Friend-shoring lumps autocracies into one unfriendly camp, emphasizing similarities and obscuring important differences among them. It is precisely the approach that prevented western countries from recognizing the significance of the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s. In today’s world, it is in the interest of democracies to expand what appear to be emerging cracks in the Sino-Russian “friendship without limits.”

Freeland’s worldview also appears highly statist. It does not address the intersecting webs of connection spanning the globe, including within autocracies. While autocrats are no doubt the dominant force in those countries, they are not the only players. A limiting of ties will give democracies fewer means of influence going forward. People-to-people networks are particularly useful when autocratic governments start to crumble from internal pressures. Democracies likely missed important opportunities to strengthen social ties within Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union. A reworked Freeland Doctrine needs to make room for multiple tracks of diplomacy, including those outside of state-to-state channels, focusing on supporting the building blocks of democracy at home and abroad.

Freeland correctly notes the naiveté of the “end of history” narrative. Her view is widely shared. Yet, in recognizing the misplaced triumphalism of the 1990s, we risk replacing it with an equally misplaced pessimism about the transformative potential of global links. Is it not possible, for instance, that the seeds of our global engagements take longer to sprout than originally anticipated, or that divisions that we see today are less stark than they would have been without the steps taken to bring rising powers into the rules-based order?

Freeland acknowledges the risks of the zero-sum logic implicit in her model and speaks to the issue of in-between states: states that do not fall neatly within the democratic/autocratic divide, such as Brazil, Turkey, increasingly India, and indeed much of the world. For Freeland, links with these in-between countries represent “the hardest question” for her friend-shoring vision. The solution, she suggests, is that these countries can, in time, reform themselves sufficiently to join our friendship circle.

What is needed is not resignation to an age of geopolitical rivalry, but creative diplomacy that seeks to explore all avenues to tackle global problems and re-establish the habits of self-interested collaboration.

Perhaps this is achievable but, depending on how it’s implemented, the approach could also be fraught with risks. The starker the line we draw between the world’s democracies and its autocracies, the murkier our relations become with countries that fall within this grey area. The quality of our links with the in-between countries will be vital to the longer-run success and legitimacy of the global democratic enterprise. Indeed, one telling take-away from the war in Ukraine is the lukewarm support offered by many countries for the condemnation of Russian aggression. Vladimir Putin’s October 2022 Valdai club speech targeted African, Asian, and Latin American states, exhorting them to reject “the West’s” attempts at “domination”. Democracies will have a lot of work to do courting countries outside of the geographic West in the coming years. Heightening the salience of the democratic/autocratic divide is the wrong way to do it.

A strict friend-shoring worldview could also present a fundamental challenge to multilateral institutions, including the United Nations (UN) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). By tacking on a democratic pre-condition for a deepening of ties, the democratic countries isolate themselves and weaken their capacity to build the coalitions necessary for exercising influence in UN bodies. NATO—so relevant today—is an organization in which the democratic credentials of some members are not beyond question. Friend-shoring risks eroding alliance solidarity.

The same argument that a political club of democracies risks undercutting multilateralism could be applied to the Ottawa-led initiative to revive the World Trade Organization, the Organization of American States, or any of the multilateral bodies that form the backbone of Canada’s foreign policy.

By setting conditions for enhanced global trading relations, friend-shoring also runs counter to market efficiency. When the world’s democracies are at their best, they are open and prosperous, not closed and hamstrung economically. If the notion is to trade among a sub-set of non-autocratic states using values-based rules, then more work is needed to define what the dividing line is and what those values are. What form do those values-based rules take: market incentives, binding norms? For Canada, the question will be which of those dividing lines will best serve its interests. Canada needs to be ready to engage with a new focus for our global trade by investing in R&D, market readiness and identifying the supply chains we need to wean ourselves and our partner democracies off of, such as Chinese manufacturing and Russian energy.

The world has become an increasingly inhospitable place for democracies. Freeland’s proposed friend-shoring contains the seeds of a constructive alternate vision, but how it is translated into a working foreign policy matters greatly. Too closed a club of democracies risks further dividing the world. Such division would leave Canada with less leverage and less global relevance. Canada has few levers to dampen growing geopolitical rivalry and should not be leading the charge toward a sharpening of the global divide. What is needed is not resignation to an age of geopolitical rivalry, but creative diplomacy that seeks to explore all avenues to tackle global problems and re-establish the habits of self-interested collaboration.

We propose a strengthening of ties globally, preserving openness and dealing cooperatively with states that are “not quite democracies” and even autocratic countries when and where interests align. While Freeland explicitly calls for such collaboration, particularly on global challenges, her wider policy thrust could work against this possibility unless it is translated into policies that foster collaboration.

A reworked Freeland doctrine would embed this club of democracies in the multilateral organizations Canada relies on for leverage, creating networks of like-minded democracies that align their diplomacy and policy positions as they engage with in-between states. This is a more instrumental and less closed approach. With this approach, Canada and other democracies would encourage states to “bind” to existing international architecture, rather than working outside of it and use international institutions as the “docking station” for new norms on democracy or values-based trade. This would avoid or at least mitigate the risk of sharpening the global divide and increase the sustainability of new norms and of the new grouping itself.

Although Freeland’s speech focused principally on Canada’s trading relations, she does see friend-shoring as something larger; as a “means of defending liberal democracy.” We see a few guiding principles as crucial for addressing the deep foreign policy implications of her vision that would have the added benefit of narrowing the “say-do” gap that can creep into international policymaking:

- Diplomacy needs to be seen as a legitimate tool of statecraft and resourced accordingly. Professional diplomats understand issues, countries, and regions in-depth, and they can forge relationships that allow them to identify early opportunities for engagement. Unfortunately, Canada’s diplomatic corps has been devalued and gutted of expertise.

- The foreign policy approach of the previous Conservative government was to cut all ties with autocracies. Diplomacy with autocracies was seen as anathema and politicized as “going along to get along.” This approach has largely continued under the current Liberal government. Earlier periods of Canadian diplomacy understood the world to be more nuanced and talking to “enemies” was seen as an instrument to influence behavior. We must rediscover this pragmatism. This doesn’t mean appeasement—engagement still requires calling out autocracies for human rights violations and condemning wars of aggression and it does not always or often work. But severely restricting ties—while it might feel purer—also does not work. There needs to be room in any new doctrine for engagement, including with autocratic states, to be seen as a legitimate tool of statecraft.

- Canada needs to consolidate and diversify its range of partnerships, particularly with in-between countries—both in bilateral and multilateral settings. These relations should be predicated on growing shared interests, not democratic credentials. Ties outside the small—and shrinking—circle of genuine democracies should be strengthened and reinforced.

- If the new “grand bargain” is with a smaller group of states aimed at growing democracy, then some work is needed to embed the building blocks of democracy in our own development assistance, foreign and security policies. It will need to include a broader spectrum of state and non-state recipients, a wider set of countries, and a broader range of elements, including, for instance, countering disinformation.

- Self-interested collaboration allows also for the growth of links below the level of the state, including at the societal and trans-governmental levels, that can be of longer-term value. Canadian diplomacy needs to make more room for multiple tracks, including those outside of state-to-state links. For this, we need coherence and engagement in our international policy that goes beyond Global Affairs Canada to include not just the rest of government, but a “Whole of Canada” approach. A foreign policy review could start this national conversation.

- Any new groupings or norms should be embedded within multilateral organizations, binding states to those institutions and norms rather than working outside them. At the same time, a structured, policy-driven and comprehensive push to improve those multilateral organizations is needed. Canada should identify and seek to rebuild the security “guardrails” that were dismantled during the period after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Cooperative norms on non-proliferation, arms control, and international humanitarian law, for example, are areas where Canada has traditionally had particular expertise. A similar approach could be applied to the development of norms around value-based trade that Freeland writes about.

- We need to also ask what would happen if Donald Trump or a Trump-adjacent US president is elected in 2024. If the US turns radically inward again and once again de-values its alliances, then any democratic club would have a gaping hole blown through it. The enmeshing of friend-shoring light within the framework of existing institutions serves as a hedge against this possibility.

Canada’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mélanie Joly, said two things in a recent interview that are directly relevant to our analysis. The Minister said that an “empty chair strategy” undercuts Canada’s international leverage and that she does not “believe in doctrine.” We both agree and disagree. Canada’s capacity to influence the international order has long rested on its unique ability to engage, including with states we don’t like. But Canada does need foreign policy doctrine, or a clearer articulation of our international priorities. This has been missing for a couple of decades now and is especially urgent in the current international environment. Articulating the Canadian values and interests we hope to protect through our foreign policy, understanding what we need to do and then ensuring we have the right people, knowledge, and policies in place to achieve that vision is of vital importance. A reworked “Freeland doctrine” could do just that.

Kerry Buck, a Senior Fellow at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa, is a former Canadian Ambassador to NATO.

Michael W. Manulak, an Assistant Professor at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs of Carleton University, holds a doctorate in International Relations from Oxford University. He is author of Change in Global Environmental Politics: Temporal Focal Points and the Reform of International Institutions (Cambridge University Press, 2022).